Running.

It’s an individual sport, but one that takes a team of support to be successful. For most, it’s a leisurely Sunday jog, a few laps of the local track or a stair session for those #weeklygains.

Ever since the stellar display of distance racing at the 1960 Rome Olympics where jogging was jolted into the spotlight, the runner’s high has been hooking hopeful hobbyists the world over. And while the sport continues to grow, attracting millions of amateur endorphin addicts to the mileage — with a record 42,906 starting the 2019 London Marathon— the level of support for top female athletes remains well below what their male counter parts receive.

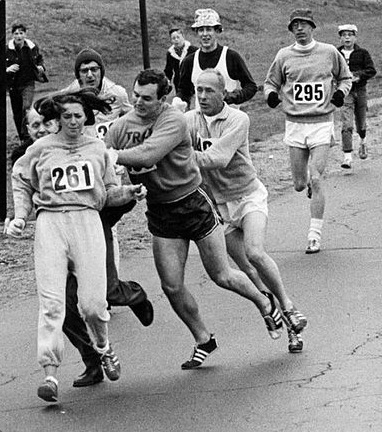

When Kathrine Switzer donned her famous 261 bib for the Boston marathon on April 19, 1967, she didn’t want to be the first woman to run a marathon. She just wanted to run.

Females have come a long way in the space of 50 years with more females than ever before breaking Olympic standards and writing their names in the history books. However, many are still doing it against all odds, unassisted and unpaid. Most work full-time jobs while supporting a family, yet each of them is among the toughest, grittiest people on the planet, fully committed to training at an insane level of excellence.

“We just want to raise the bar and work hard.” Caitlin Keen, Former SMU Cross Country Runner and now Olympic hopeful in the marathon, said.

Working hard to be phenomenal is a daily task for any elite athlete, but adequate recovery and balance is another key component to success, and one that many top females are being cheated out of.

“It’s been very tough over the last couple years, I was sick in Rio, then missing out on the World and Commonwealth games semi-finals both by one spot and losing my national title this year, … it creates a lot of pressure.” New Zealand 800m Olympian, Angie Petty said.

Petty has represented New Zealand at the Olympic, World, and Commonwealth Games, as well as won gold at the 2015 World University games. She is a New Zealand record holder in the 1000m and an eight-time national champion in the 800m, yet the support available to her is limited.

“I am very grateful for the support I do get like regular physio, gym use, and some funding towards travel, but It’s tough knowing girls who run similar times are on $60,000 contracts overseas,” Petty said.

For Petty, the mental resilience required to move on from performances unrepresentative of her full ability becomes incredibly draining.

“It’s tough, I have to juggle training hard, recovering and holding down a full-time job. My PB (personal best) is from 2015 but I still feel I can go faster.” Petty said.

Despite struggling to find adequate funds, Petty’s passion along with the support of family and friends is keeping the dream alive.

“I really do enjoy it so much and want to keep using this gift … It’s a tough sport and there are many other athletes in even tougher situations, I’m still so thankful to be on this journey.” Petty said.

https://www.facebook.com/angiepettyruns/posts/1731042773706093

Petty, like the deepening fields of high-class female athletes worldwide, proves a great inspiration to many young runners, yet when the day-to-day reality of life at the top is revealed it’s easy to see why young women leave the sport.

Perhaps one of the biggest gains for women in sport can be seen via the US Title IX legislation that ensures gender equality within the collegiate system.

“The university system in America provides an environment where the main facets of my life have a cohesion like never before, as well as support, resources and learning opportunities I could never have dreamed of having in New Zealand,” High Point University and New Zealand distance runner Tessa Webb said.

Equity in college sport has been instrumental in laying the foundation for the next generation of females to flourish, yet beyond college, the prospects of making it pro are still exceptionally hard with big companies requiring more than just exceptional athletes.

“I believe in this increasingly digital age female athletes are being judged more than ever based on how they look, with Instagram engagement statistics mattering more to a lot of brands than personal best times or championship medals,” Webb said. “It isn’t enough for our performances to speak for themselves; as female athletes, we are expected to be the full package.”

Athletic marketing in general, but especially in the running world is heavily focused on giving it everything with the original Nike slogan, “just doing it” being a common vernacular. While these messages serve motivation, they also display the often unrealistic expectation of total sacrifice to be ‘good.’

“Athletes are expected to give up everything; our social lives, financial stability, and especially health in order to perform; anything less and we are seen as not dedicated enough,” Webb said.

For women, in particular, athletic marketing provides a mixed bag of messages. Brands sell the idea of sacrifice and hard work paying dividends with images of women who have it all; family and athletic success. And while both family and professional sport can be achieved in harmony, the reality of transition and recovery periods is rarely as clean cut and glamorous as promotional “post-baby” posters will make it seem.

“We are moving in the right direction, but major companies that say they support females aren’t willing to put money where their mouths are when it comes to supporting those females athletes who choose to start families, it’s conflicting,” Keen states. “Companies expect women’s bodies to be able to bounce back — like they didn’t just spend 9 months growing another human life!”

While females continue to break barriers, win prominent races and close the gap in competition, the collective sporting world remains at a standstill over parental leave, equal pay and sponsorship deals. Equity, Webb believes, can only be achieved through greater transparency in fees paid and collective athlete boycott action in response to those companies failing to provide identical paychecks.

“Women shouldn’t be expected to toe the start line for anything less than the men.” She said.

Determined to not let their window of opportunity close while waiting for greater sponsorship, a group of dedicated semi-professional runners in Fort Worth Texas have taken matters into their own hands.

Like any good idea, the Fort Worth Distance project was formulated during a training run by a few budding athletes seeking a team environment to help them train for the 2020 Olympic Marathon Trials. With a large cohort of up and coming athletes right on the cusp of the trails standard, the team was modeled off elite Californian group “the Janes” to aid development.

“We came together with a common goal: To run, compete, have fun, and qualify as many girls for the Olympic Trials as we can,” Keen said.

Two years later the team is a fierce bunch of post-collegiate athletes all specializing in the marathon and all either working full-time jobs, completing grad school or raising a family.

“We are unique because of how much is demanded of us outside of running and how much of ourselves we are still able to give to our craft,” Keen reiterated.

While the group is not funded, they aren’t letting this hold them back. Through giving back to their community and appearing and volunteering at local running events they have gained a partnership with Fort Worth Running Company, which provides them each 2 free pairs of shoes per year.

For the Fort Worth Distance Project, it is apparent passion and team outrun the support any amount of funds could provide. In fact, for Keen, the 7-year-old who found her self-confidence as she jogged the blocks home from tennis training, the chance to hit big and prove the naysayers wrong has always been the underlying motivator.

“Resilient” is the one word she picks to describe herself. A college walk-on to a division one scholarship athlete; Keen channels that same determination as she works towards her post-collegiate goals.

Recognizing the value of real role models, the Fort Worth Distance Project pride themselves on transparency and sharing their journeys with followers over social media — be it a long run snap or #momlife!

“I am very transparent about my journey because you cannot expect to be inspiring if people can’t relate to you,” Keen said. “I never set out to be an inspiring person I just think my journey hit home with a lot of people realizing that it doesn’t just take talent to get you to the top.”

https://www.instagram.com/p/Bq5hOeFhtQ9/?utm_source=ig_embed

While more funding is needed at the semi-professional level to develop and aid talented athletes out of college, the Fort Worth Distance Project continues to take the challenging scope in their stride, focusing on the essential elements their team environment provides and running with the demands of everyday life. The group has proven they are of an elite caliber currently qualifying three individuals for the Olympic Trials in Atlanta next year.

“Your mind and beliefs are going to control everything,” states Keen. “You have to believe in yourself more than anyone else is ever going to believe in you.”

Funding in female athletics may remain elusive and uncertain, but one thing is a given, women who refuse to take no for an answer will, as Kathrine Switzer did 50 years ago; run on!