A sniff.

A stop.

A look.

A hand.

A helping hand. But not any helping hand.

A furry paw.

A furry paw that sends a message.

A message that alerts Janet Smith before it’s too late.

“What a beautiful dog!” pedestrians will say. But he is not just another golden-coated pup walking the streets and chasing squirrels and rabbits.

Hudson is one of five registered service dogs with Disability Accommodations & Success Strategies (DASS) at Southern Methodist University.

Smith uses Hudson for medical alerts that she cannot detect on her own.

Hudson gives her his paw when he smells the scent that sends her to a state of unsteadiness. A scent that only Hudson can smell preventing Smith from being in an unhealthy condition.

“I can’t feel it until it gets really bad. I have on my watch set for high heart rate alerts, but it takes a while for it to even get to my phone,” Smith said. “By the time it’s already up, it’s too late.”

The popularity of having a service dog is rising gradually. Service dogs change lives for people living with a disability by using their powerful sense of smell.

Disabilities range from food allergies, diabetes, mobility, anxiety and unknown diagnoses. Service dogs prevent their owners from going into life-threatening conditions.

They also provide a sense of health security for the person in-need to maintain good mental health.

“They can be there to help you socialize,” Miriam Richard said.

Richard, a passionate mom who has children with food allergies, is a dog trainer and co-author of Dogs in Vests, which explores living life with service dogs.

“They can help by reminding you to take your medication,” Richard said. “It’s easy to time that. If you are super depressed, it gets you out to walk – you get the sunshine. That changed you.”

Hudson helped Smith with her mental health by having to get up early to take him out on a walk and by forming a daily routine.

“It was always in the back of my mind,” Smith said. “Mostly when it started, I isolated myself and didn’t want to spend much time with family and friends since I didn’t have the energy or feel well enough to. I was so depressed because I couldn’t do anything. ”

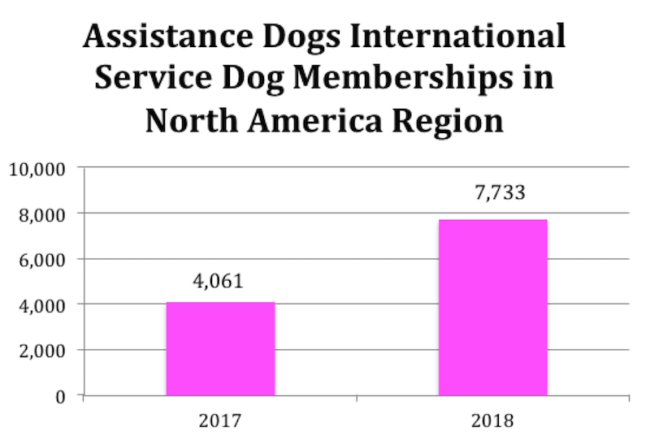

Assistance Dogs International (ADI) is a worldwide coalition that places and trains assistance dogs. ADI has seen an increase in service dogs from data collected in 2017 and 2018 just through ADI membership alone.

Certified dog trainer for Canine Solutions Dallas, Valerie Fry ABCDT-L2, which is Animal Behavior College Dog Trainer Level Two, has seen a rise in service dogs especially in generations millennial and younger.

“It’s amazing to see the level of responsibility they are taking in their own health journey at such a young age with a service dog that is their sole responsibility,” Fry said.

In eighth grade, Smith began to feel as if she had been on a series of rollercoasters. She experienced dizzy spells that forced her to have to stop what she was doing at any given moment – school and horseback riding.

“In high school, it was like 10th grade where I couldn’t go to school anymore, and I had a teacher come to my house because I was dizzy all the time the whole entire day,” Smith said. “I couldn’t do my school work, so I would just have to rest and save my energy for a few hours a day where I could work and everything.”

Smith thinks she has Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome, or POTS, a disease that affects blood flow circulation and causes heart rate spikes and fainting tendencies.

The key word is ‘thinks.’

Some doctors say yes, others say no. Doctors have had a hard time pinpointing the correct diagnosis, which encouraged Smith to consider getting a service dog.

“It was 12th grade when I was like, ‘Ok, I am not getting any better and I want to go to college,’ so I thought that was my last resort,” Smith said.

She is now a student at Southern Methodist University studying Biology and Spanish.

Many people who have a disability but don’t have a service dog usually fear the financial investment involved with getting a dog and training it appropriately.

“The average cost is 10,000 to 30,000 dollars,” Richard said. “A seeing eye dog is over 100,000 dollars because 55 percent or so do not pass.”

However, Richard says that service dogs are 85 to 90 percent accurate, just like medical equipment. And even better, they can be by the owner’s side at all times and provide emotional support as well.

Abbey Copeland is a student at Oklahoma City University, and she has dealt with Type 1 diabetes for six and a half years. However, she does not have a service dog because of the cost.

“I would love to get a service dog, since I don’t know if my blood sugar goes to a low at night without my mom calling me,” Copeland said. “If I were able to have one, I wouldn’t have to worry that I won’t wake up.”

In the early months of Hudson’s training, Smith wore a heart rate monitor for two weeks.

“I had to record every time something was wrong,” Smith said. “So I would record every time he pawed me, and it was correlated with everything so we could see his accuracy. I have the Cardiogram app, so I like to see throughout the day, ‘Ok, he got that right.’”

Two-year-old Hudson is a purebred goldendoodle from Lonestar Doodles in Weatherford, Texas. The dog breeds that most commonly become service animals are golden retrievers, Labrador retrievers and poodles.

However, this is not to say that other dog breeds can’t be service dogs.

Erica Massey, a graduate teaching associate and Ph.D. student at SMU, has celiac disease. Her Belgian Malinois, Deacon, is attached to her side 24/7 and sits when he smells a plate infested with gluten.

“He was from a military police litter,” Massey said. “When they temperament tested the puppies, it was very clear that he was not going to be a good candidate for that.”

Deacon’s intelligence encouraged his breeder to find someone like Massey who was actively looking for a service dog she could train to sniff out gluten.

“If you have celiac disease, especially if you have a pretty severe representation of it, even just a tiny little bit can make me really sick. Which is hard. Like you can’t really go out to eat and feel safe,” Massey said.

There are different methods in training a service dog depending on what type of service the dog is expected to perform. Most commonly, clicker training along with hiding particular scents around a room, in tennis balls, and under the dog’s food bowl train a dog to get familiar with specific scents.

Fry strongly believes that a service dog reacts best when their handler trains them.

“This cuts out a huge portion of time that it takes for an organization to fully train a dog and then transition it to a home and get that dog more accustomed to working for someone else,” Fry said. “Which by that time, that dog could be four years old.”

Massey trained Deacon to accurately smell four types of flours commonly found in foods by going to the bulk section at Whole Foods and filling empty lip balm containers with the flours. Massey would poke holes and hide the scents in different places for Deacon to find.

Smith couldn’t just go to a supermarket and buy the scents she wanted Hudson to learn. Instead, she had to train Hudson to smell her body chemistry.

“When I was feeling horrible, I’d take a sample,” Smith said. “I’d just take a washcloth and rub it on my skin and get sweat, and I would put that in the freezer. And so, we started training him to find that scent.”

Each time a scent training game occurs, the dog becomes smarter and more reliable. For instance, Hudson raises an eyebrow and paws at Smith when he senses a change in her heart rate.

These moments happen just a few minutes before she starts to feel bad.

“I know, ‘Ok, go quickly find a spot to sit down and watch my heart rate, wait for it to go up and then back down,’” Smith said. “He will usually paw once or twice, but sometimes it’s bad. It’s like 15 times where he’ll keep doing it. You can tell that he knows that’s his job.”

Hudson knows Smith inside and out. She sees Hudson change with his facial expressions and how he interacts with her, but most people who are not close to Smith and Hudson can’t tell, and they think Hudson is begging.

Her close friends will tell Smith to listen to Hudson because his mannerisms are different than usual.

“It took me a while to realize, ‘Hey, he’s right, I’m wrong,’” Smith said.

Service dogs are not required to wear vests in public under the Americans with Disabilities Act or ADA, and if the handler is given any problems by public entities, the only two questions that can be asked are: Is this a service dog? What service do they perform?

Fake service dogs are a concern, but a trained eye looks to see how in tune the dog is with their handler and how obedient is the dog. Service dogs are allowed to bark in public if they have a reason such as for protective purposes, but the bark should not linger.

“The dog is still a dog,” Richard said. “You can’t take the dog out of the dog.”

As much as service dogs love to play with tennis balls, roll in mud and bark when they feel threatened, their top priority is to provide a helping hand that the handlers depend on to live their life.

Hudson does just that. Even if he is not literally saving a life, he is changing Smith’s life by offering his helping, furry paw.

“The stuff I have going on can’t kill you, but it just makes you unable to live life,” Smith said. “There’s been a lot of times where I’m like, ‘Oh my gosh, I’m so glad he did that,’ because then I can continue on with my day versus if he didn’t, day after day, I’d just be dizzy all day and I probably wouldn’t be in college.”

*Janet Smith is a pseudonym.