Hours of darkness and power outages.

Empty pharmacy shelves.

Mile-long lines for gasoline.

Mass protests.

This is Lebanon in 2021.

Rula Tareq visited three years ago, and the country looked vastly different.

“It’s unbelievable,” Tareq said.

Tareq described the moment she realized the extent of the crisis in her birthplace. Tareq and her two younger siblings had just stepped off of a plane from the United States and onto Lebanese soil in July 2021. Two airport employees helped load their bags into the car taking them to their family’s village.

They joked with her in Arabic, hoping for a tip.

“Don’t worry, we’ll take care of you,” Tareq replied back.

She handed each of the men a U.S. $20 bill. They looked at her in shock.

Tareq walked out to the car where her uncle was waiting to greet her and her siblings. She mentioned to her uncle what she had tipped each of the men.

Again, the same look of shock.

“His jaw hit the ground. He was shaken,” Tareq recalled.

Tareq still had not grasped the peculiarity of her gesture. Her uncle asked her if she knew what a $20 bill meant in Lebanon.

In July 2021, a U.S. $20 bill was worth over 450,000 Lebanese pounds on the black market.

Since 2019, Lebanon has suffered one of the worst economic collapses in world history. Its currency has lost 90% of its value, inflation has sky-rocketed and electricity, medication and fuel are scarce. The World Bank has called it one of the “most severe crises episodes globally since the mid-nineteenth century.”

August 2020 would bring more destruction upon the country.

On Aug. 4, 2020, over 2,700 tons of ammonium-nitrate exploded in the port of Beirut, Lebanon’s capital city. Ammonium-nitrate is a chemical compound commonly used in agricultural fertilizer. At least 216 people were killed, over 6,000 were injured and over 300,000 were left homeless.

The devastating blast, one of the largest non-nuclear explosions in history, spiraled the small country into an even deeper economic depression, many of which say was fueled by corruption and carelessness at the highest levels of the Lebanese government.

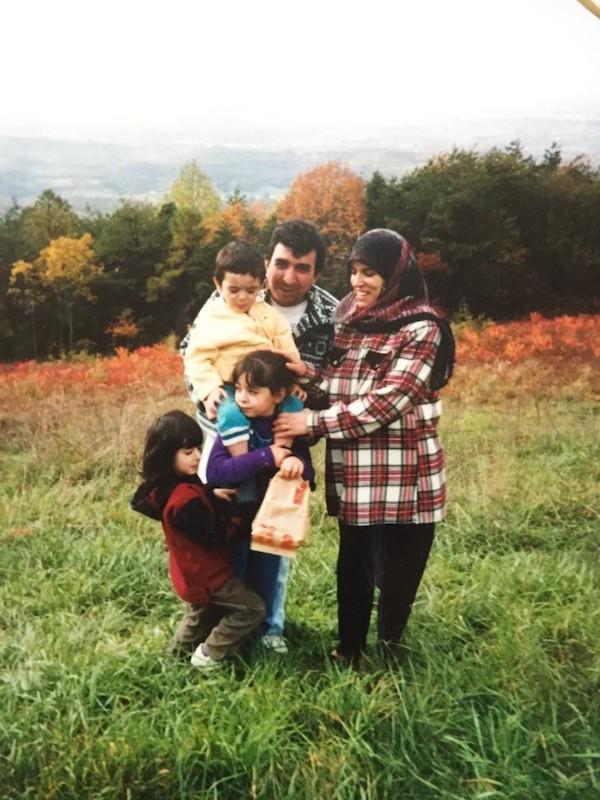

Tareq arrived in the United States in 1999 at four years old. Lebanese nationality law prevented Tareq’s mother from passing her Lebanese citizenship on to her Iraqi husband, so the family had refugee status in Lebanon.

Reliable healthcare, quality schooling and almost all government aid quickly became out of reach for the family because of their status.

“You’re very limited unless you are a millionaire, then obviously life is much different,” Tareq said of the opportunities for refugees in Lebanon.

They made the decision to leave, and the United States held the same shining allure as it does for many immigrants: hope for a better life.

Tareq, now 26, works as a communications professional in McLean, Virginia. She returned to Lebanon this past July with her two younger siblings, Miriam, 23, and Abdullah, 21. The main reason for their trip? To visit their critically-ill grandmother.

“In March, her health started to deteriorate and we just weren’t sure with COVID-19 how we were going to be able to make it happen,” Tareq said. “Airports had been closed, so we took this chance because she had started to get sick.”

They traveled to their family’s small village of Ebba in southern Lebanon. Tareq said her grandmother, Roukaya Tarhini, had struggled with a variety of health issues throughout her life, from diabetes to blood pressure problems.

“As a family, we’ve always made it work. No matter how much the medicines cost, we’re going to buy it,” Tareq said, explaining how her family had financially supported her grandmother abroad. After the economy started to collapse, new issues emerged.

“The problem is the access to the medicine was just not there. We’re driving to 10, 12 pharmacies a day to find medicine for her,” Tareq said of finding medication in Lebanon.

Because of the crisis, access to medication has become virtually nonexistent.

Tareq and her siblings brought suitcases of medicine to Lebanon in July because of the shortage.

“People don’t even have access to ibuprofen. People are suffering and they don’t know what to do,” Tareq said.

Fuel and electricity shortages also plague the country. As Lebanon failed to provide 24-hour electricity to its people, they started to turn to generators to provide electricity when the government was not.

“Most small villages, including ours, had generators, so as soon as the government electricity would cut off, the generators would cut on and you had electricity 24/7,” Tareq said.

The patchwork system worked for a while.

And then came the fuel shortage.

“This past trip, we had electricity four hours on, four hours off, but at night we would typically lose it all. There would be no electricity,” Tareq said.

Tareq said in the weeks following her departure from Lebanon, her family’s home in Ebba had electricity for a total of an hour a day.

“The government electricity would come for half an hour a day. That’s it,” Tareq said.

Because of the lack of fuel, the people of Lebanon have been forced to turn their generators off, succumbing to hours of darkness, spoiled food in their refrigerators, and dead cell phones.

“There is not a single thing in Lebanon that is not deteriorating. Every single thing in Lebanon is falling apart. Nothing has been untouched. And it’s only getting worse,” Tareq said somberly.

The World Bank has called the crisis “deliberate”, caused by “continuous policy inaction and the absence of a fully functioning executive authority.”

“The government has failed its people. And its failed the country as a whole,” Tareq said. “Lebanon is so beautiful and it has so much to offer. And year after year it is brought down by these same politicians who have been in the same positions for 30-plus years.”

SMU junior Ayah Krisht, born to Lebanese immigrants who still have family in Lebanon, said it can be difficult living in America knowing Lebanon is engulfed in turmoil.

“It’s definitely been stressful, because you’ll hear things on the news and know we need to call this person to make sure they’re okay,” Krisht said.

Krisht and her three siblings, all of which attended or are attending SMU, have had a multitude of opportunities that they otherwise wouldn’t have had in Lebanon.

“It makes me realize why my parents went through such a lengthy process to move here,” Krisht reflected. “The whole reason we moved here was so that we wouldn’t undergo those experiences.”

Both Krisht and Tareq acknowledged that it is becoming more and more challenging to leave Lebanon.

“You are in an open-air prison, suffering emotionally, physically and mentally, financially,” Tareq said. “There are no options.”

Natalie Nanasi, Associate Professor of Law at SMU Dedman School of Law, specializes in humanitarian immigration law.

“So much of the immigration system really is so dependent on geopolitics at the time and domestic politics at the time,” said Nanasi, who also serves as Director of the Judge Elmo B. Hunter Legal Center for Victims of Crimes Against Women.

“Much like everything else in the world, because of COVID-19, things in the immigration system slowed down. The typical wait for a hearing in immigration court, even pre-COVID-19, was a couple years,” Nanasi said. “Now, with institutions struggling, you’re seeing the effects of that in the immigration system as well. Everything is taking years.”

Nanasi emphasized the challenges many immigrants face while waiting years for their applications to be adjudicated.

“Our system is just broken. People are being separated from their families. I think we would all agree that this is not the way it should be,” Nanasi said.

With limited options and dire circumstances, Lebanese citizens are suffering, with little possibility for relief.

“Lebanese people are always described as resilient,” Tareq said. “But people are tired, and they’re vocalizing it. They’re tired of fighting for their lives every single day against an invisible actor who has penetrated every single aspect of their day-to-day life and taken it away from you in some way.”

Tareq said the mishandling of the crisis by the political elite is costing people their lives.

“They are dying in hospital beds and politicians are looking in the other direction,” Tareq said.

Tareq’s grandmother passed away on September 25th.

The Tareq family is not alone in their experience. What they have gone through is emblematic of the plight of families across Lebanon, who are living without electricity, medicine, fuel and other basic necessities billions of people don’t think twice about.

Tareq speaks gratefully of her opportunities and life as an immigrant in the United States.

“My family was lucky. We are not better than anyone else,” Tareq said. “That’s what I always tell people when we go back. I’m not any better than you. It could happen to you. I just got lucky.”