Many SMU students have connections to Palestine and Israel. Navigating their often drastically different perspectives offers a look into the fraught histories shared between the two communities.

The variety of often conflicting perspectives emerges from different backgrounds and shared experiences. Israel is seen by many Jewish people as an important part of their identity, culture and faith. For Palestinians, however, Israel’s founding and continued expansion into Palestine through illegal settlements denies millions a home and opportunity.

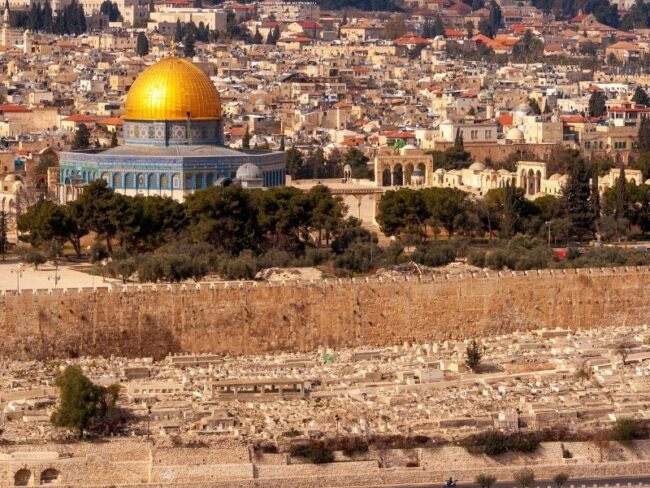

The state of Israel was established in Palestine after the Arab-Israeli war in 1948. In the wake of the wars, however, over 700,000 Palestinian refugees fleeing violence were displaced. These refugees have not been able to return to their former homes in current-day Israel, and were the first of a global Palestinian diaspora that now contains over 7 million people. The city of Jerusalem further complicates the conflict, which contains holy sites for all three major Abrahamic religions.

“Jerusalem is a city that brings together these cross currents of different people from different areas, different thoughts, and different beliefs,” said Rabbi Heidi Coretz, the Jewish Chaplain at SMU. “They come together to honor God and honor God’s creation of all of humanity.”

Lior Kremer, co-President of Hillel at SMU, is one Jewish and Israeli student who feels drawn to the region for its connection to her faith as well as her own Israeli identity.

“I’m very connected to Israel, I want to eventually go back and work there, raise my family in Israel. I want to make Israel better,” Kremer said. “I want to make the area and region more calm and better for everyone. And I think it starts with us, by having the right intentions because I feel like the politicians we have right now are not necessarily doing the right job for it.”

Many Palestinian students also have a strong connection to the region, and consider the area an integral part of their identies and family histories.

“Growing up, my parents constantly reminded my six siblings and I of the importance of remaining cognizant of our identities as Palestinians,” said Sanaa Ghanim, a second year SMU law student. “To my parents, the most important piece to this is visiting home as often as we can. My summers in Palestine are spent making up for lost time with family and learning more about Palestine through conversations with family members.”

The West Bank and Gaza are both recognized as Palestinian territories under Israeli occupation. Gaza, where over 2 million people live on a 140 square mile piece of land, is the center of much of the violence seen during flashpoints such as those from the past summer. From the Israeli perspective, Gaza is not an occupied territory since Israel officially disengaged the area in 2005 and the region is now governed by Hamas. Still, Israel controls Gaza’s air and maritime space as well as several of their land crossings and reserves the right to enter at will with control over water, electricity, and other utilities.

The Israeli military presence and the extreme poverty that millions of Palestinian refugees face means that historical wounds bleed into the present.

“I’m from the south of Lebanon, which has villages where my father is from that had been occupied by Israel. The house that my grandfather built there at some point, also had been destroyed and he had to rebuild it because Israeli soldiers had destroyed it,” said Dima, an SMU junior who requested we only use her first name for safety reasons. “Even whenever we would go to the village on the weekends, we would hear Israeli drones just around the area constantly monitoring. It’s just it’s always been a part of my life and that’s how I’ve learned about it.”

The abject desperation is one of the few indisputable factors in the region’s conflict. Director of the SMU Embrey Human Rights Program Dr. Rick Halperin said that he was in disbelief at the living conditions in Gaza when he visited, and described them as the worst he had ever seen.

“There was no mail coming in, the electricity had been cut off. There was no garbage pickup. People would take their trash down to the Mediterranean and let the tide take it out. It was beyond horrific,” Halperin said. “I want to be clear that I am not pro-Israeli, I’m not pro-Palestinian – I’m pro human rights. I believe that all people, even in areas of tension and conflict, still must be afforded the basic rights of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.”

Even beyond Palestine, the intensity of the occupation takes a toll on those who are connected with it. Dima said her relationship to the region as an Arab American student makes her feel alienated from others on campus.

“Even though people tried to act accepting towards Muslim Arab students, in reality they don’t really respect their human rights. I just feel like a lot of groups aren’t supporting Palestine, which is really disheartening to me as a Lebanese Muslim student,” the junior said. “You’ll respect my diversity and my background when it’s useful to you, but when it actually comes to taking a stand on something important, you won’t do it.”

Many Israelis feel the problems that Palestine faces are due to their leadership with Hamas, the de facto governing authority in Palestine. They also believe that the difference in coverage of Hamas’s war crimes versus Israel’s embodies a persistent double standard.

Those sympathetic to Palestine point out that Hamas has far inferior offensive and defensive military capabilities than Israel, which receives $3.8 billion of annual military funding from the United States per a 10-year Memorandum of Understanding signed in 2016. However, some Israelis feel that Israel’s significant military funding and responses toward Hamas are necessary measures of self-defense.

“Does that make us less of a victim because we can protect ourselves and we don’t have victims like actual deaths? I don’t condemn that,” Kremer said. “Hamas is a terror organization, but it’s supported by Iran and they get weapons from them. So it’s not really true to say they’re that much weaker because they have the support of a lot of other countries.”

The occupation and tension in the region is unlikely to go away soon. The overarching issue can seem black and white, but the underlying politics make it difficult to untangle.

“We always listen to Palestinian voices. We always listen to Israeli voices, and I hope we come away with an understanding that this is an incredibly complicated set of problems,” said Dr. Robert Hunt, the Director of Global Theological Education. “We simply cannot vilify or dehumanize one side or the other…neither society is monolithic. They have their conflicts within themselves, and that makes the situation more complicated.”

Despite the complications and animosity that the conflict generates, SMU professors, leaders, and students hope that greater dialogue and understanding will pave the way towards an eventual solution.

“I know that this problem must include human rights education,” Halperin said. “Whatever the answers to solving these difficulties are, they are worthless, and bound to fail. working with young people about human rights education has to be a part of the solution.”

This story was updated August 12, 2024.