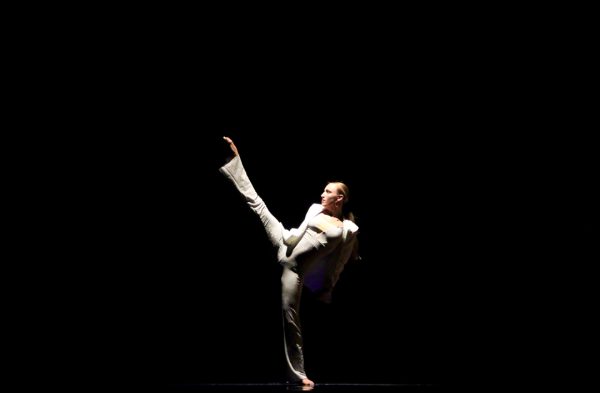

I settled into position in the Bob Hope Theater and prepared to watch from behind the curtain as upperclassmen dance majors warmed up on a dimly lit stage. I heard they were performing “Diversion of Angels,” a piece by a choreographer and dancer Martha Graham. The lights came up and illuminated a woman dressed in white and a man in brown pants. I watched in awe as dancers glided across the marley floor in colorful flowing fabrics to a romantic musical score. Sitting in that darkened theater, I felt the air shift as each dancer moved powerfully with expression. That performance marked the beginning of what became an obsession with Martha Graham. I needed to understand how Martha Graham captured so much emotion and meaning in movement. I soon discovered her legacy was more than modern dance. She was the catalyst of a revolution in how we understand the body, emotion and art itself.

A pioneering force in modern dance, Martha Graham revolutionized the art form and choreographed more than 180 works. She developed a technique built on the central movements of contraction, release and spiral. Her choreography, often inspired by mythology, psychology and the human condition, pushed the boundaries of what dance could be. Through works like “Appalachian Spring,” “Lamentation” and “Diversion of Angels,” Graham showed the world that movement could convey grief, joy, passion and everything in between.

I spoke to former chief dance critic of the New York Times, Alastair Macaulay, prior to starting this story, confused about how to begin to articulate my strong feelings towards Graham and her work. Macaulay pointed me to an essay in Arlene Croce’s book titled “Writing in the Dark, Dancing in the New Yorker.” Croce wrote passionately of Graham’s devotion to self-discovery and discipline. Macaulay and Croce both believed Graham was a feminist heroine.

“The fact that she doesn’t live for love is the most important of all,” Macaulay said. “[Her] early work heroically makes you see the woman as being sufficient to herself. When Graham begins to add men, it doesn’t necessarily make it better.”

Graham championed the idea that the female body could be an instrument of raw, unfiltered expression, capable of conveying not only beauty but also rage, despair, ecstasy and love. For me, this notion expands beyond the studio and emphasizes the importance of women’s impact on the arts in a male-dominated world.

Jesse Factor, a former Graham dancer and current dance professor at Point Park University in Pittsburgh, described the first time he saw Graham’s work.

“I had never seen the human body move that way. It was so powerful, so expressive. It was a combination of grace and athleticism,” he said.

Factor said teaching and performing Graham’s work has empowered his sense of audacity.

Just a few weeks of practicing the Graham technique at the start of my freshman year was enough to intrigue me. I learned from dance Professor Myra Woodruff, who danced directly under Graham as a company member, taught at the Graham School for 10 years and performed in more than 25 ballets from the Graham repertory.

Woodruff had a thin frame and expressive personality. She recited the words of Graham like holy scripture, and her class was like church. Woodruff was everything I assumed a dancer should be.

I remember her saying, “Martha believed the arms came from the back because they were once wings. Find your wings, and use them. You can fly.”

I have never, and will never, meet another human quite as incredible as Woodruff.

The Meadows dance department still places importance on modern dance techniques. Christopher Dolder, chair of the division, and Anne Westwick, a professor of practice, pass on Graham’s teachings, along with their interpretations of her values.

“I’m not trying to make you the artifact of Martha’s art,” Dolder said. “I am trying to use Graham, and Anne is using Graham to give you a suit of armor, to give you a foundation by which you can go try many things.”

Graham’s impact touches all of those who encounter her teachings, even after time away from training. Erin Vonderhaar is a professional dancer well-versed in many mediums of the industry who values her Graham training from SMU.

“It’s hard to understand when you’re in the moment, and then it’s weird, it kind of sets in your body, and the longer it sets in, the more you start to understand it,” Vonderhaar said.

She also said the quality of her movement across all dance styles is stronger because of her technical Graham background.

After four years of working on the Graham technique, I’ve also noticed my core is stronger, a necessity for mastering Graham’s signature contractions and releases, which demand control and precision. My posture and alignment improved, and movements that once felt rigid or intimidating are now second nature to me. This physical strength has not only made dancing easier but also deepened my emotional connection to the choreography. Each gesture feels more intentional, each contraction more intense, as if my body is finally in sync with the emotional depth the technique requires. Dance is not just about moving, it’s about building a body that is truly expressive.

Graham broke barriers for women in the arts and weaved together an approach that elevates dance to a fine art. For me, Graham’s legacy taught me that vulnerability is strength and that true expression lies in embracing the divine imperfection of human life.