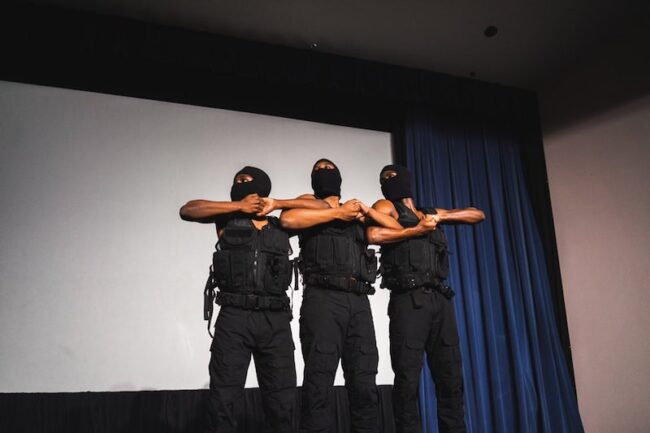

Last fall, three men clad in black tactical vests and ski-masks entered Hughes-Trigg auditorium. Someone called SMU PD.

That same evening in Hughes-Trigg, Alpha Phi Alpha president Jabari Ford was preparing for the fraternity’s annual probate show. Probate shows are more typical to the National Pan-Hellenic Council, a council composed of historically African American Greek chapters. The high-energy, choreographed shows are a unique and cherished tradition where new pledges, or probates, are officially revealed as a part of their respective chapters in front of a crowd of friends and family. That night, however, Ford began receiving countless calls about police outside.

“I have a million other issues that I’m concerned about at this point, so I’m like, ‘Oh, it doesn’t matter to me, like, the police?’” Ford joked. “There was a high school football game going on on campus at this time so I was like, I don’t need to worry. They’re on campus as crossing guards for the game. Don’t worry about it, just tell them why you’re here and just get on by.”

The calls kept coming, and a sudden flood of people walking into the auditorium tipped Ford off to the fact that something wasn’t quite right. It wasn’t until he saw two police officers walk in with guns that he began to understand what was happening.

“I’ve never seen anything that big,” Ford said, recalling the guns the officers were carrying. The police warned Ford of an active shooter situation, and he realized the police were there because of his probates, who, as per Alpha Phi Alpha’s annual show theme, were dressed in black tactical vests and ski-masks.

SMU student Logan McElroy initially de-escalated the situation with “cultural intelligence on the fly,” showing the officers the event flyer and explaining the concept of a probate show. The situation could have ended very differently without McElroy’s clarification; Ford was later told by the then Dean of Students Dr. Evelyn L. Ashley that several intelligence agencies were preparing to respond to the perceived shooters.

“Logan literally saved their lives that day,” Jabari Ford said. “Admittedly we should have gotten there a little earlier and then should have gotten changed in Hughes-Trigg…It was just, it was probably one of the scariest experiences.”

Fast-forward to May. The shock of George Floyd’s murder in Minneapolis reverberated across the nation, unearthing long-ignored conversations about race and law enforcement. SMU was no exception.

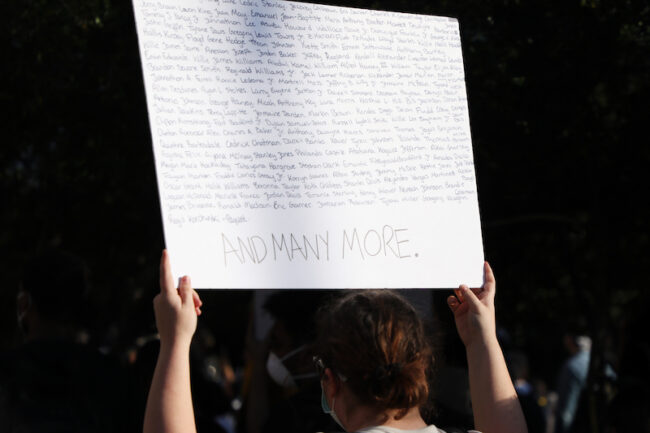

It began on Twitter where Black SMU students recounted their personal stories of discrimination, humiliation and frustration on campus with the hashtag #BlackAtSMU. Many of the stories criticized SMU PD for reinforcing a discriminatory environment on-campus.

Got stopped by SMU PD for “matching the description” of a non-student who was hanging out in the dorms. After showing my ID, the officer still called back up. I was surrounded by 3 squad cars when they admitted I didn’t really match the description- I was just black. #BlackatSMU

— Dorothy Dangerous (@_Losteele) June 2, 2020

National movements to abolish the police came out of the endless interactions mirrored around the country, highlighting the vastly different perception and experiences that Black Americans have with the police. The demands of this abolition movement vary depending on the locality, yet they are seldom, if ever, about simply eradicating police.

Proponents of the movement claim the police are overextended and respond inadequately to issues such as drug use, sexual assault and mental health. Many suggest that these issues could instead be more safely and effectively addressed by divesting from the police, and redirecting that funding towards community-based social programs.

“I think the Black Lives Matter movement has been a big kick in the ass to literally everybody in this country to kind of reevaluate our implicit biases, to reevaluate how radical we should be, to reevaluate how serious about this issue we should be,” Ford said.

SMU Police Captain Jimmy Winn, who has been at the university for almost 20 years, oversees more than 30 SMU PD officers who are in charge of patrolling and securing the campus. According to Captain Winn, the university has a community-based approach to policing and officer training that sets it apart from a typical city police department.

“As far as the state of Texas is concerned, an officer has to complete 40 hours of training every cycle, which is every 2 years. Our department and police officers double that every year,” Captain Winn said. “With our cycles we always have a cycle on cultural diversity, de-escalation, and stuff like that on every police cycle…we have at least 80 or 120 hours per cycle per officer.”

In addition to officer training, Captain Winn says discriminatory behavior is not tolerated.

“When we find an officer that has bias or has been committing questionable police activities, we have no problem just getting rid of them. And that’s just all,” Captain Winn said. “There’s no tolerance in our department for that type of behavior. Period.”

Since 2017, one police officer has been dismissed for discriminatory behavior. Yet students’ lived experiences may attest to how the line between discriminatory and non-discriminatory behavior is not so clear-cut.

At SMU, a new abolition movement has become a platform for students to demand greater transparency and accountability from the administration in a bid to better understand the processes behind campus policing. Public records like the annual Clery Report and crime logs provide data, yet both SMU PD and students point to how that data provides a significantly limited perspective.

Ben Nwokoye, a rising senior and former RA, suggests that transparency should also apply to interactions such as traffic stops or suspect searches.

“If you’re looking for a six-foot black male, and you’re just stopping me…if you’re asking me if I go to school and I have a backpack on and things like that, I’m gonna immediately view that as a micro-aggression, no matter what,” Nwokoye explained. “You could at least let me know that you’re looking for someone and that I might fit the description…at least I could understand why you’re stopping me.”

Some students involved with the abolition movement hope to minimize and eventually eliminate the presence of Highland Park, University Park, and Dallas Police on-campus, all of whom currently share jurisdiction of SMU’s Main Campus.

Captain Winn says that the shared jurisdiction is a necessary result of the campus’s urban location, but does acknowledge the discrepancies in experiences and protocol that can occur when students interact with four police departments rather than one.

“It just depends on circumstance and the situation, you can’t really have a one-fits-all when it comes to that,” Captain Winn said. “But the thing that I would say is get to know the police department where you’re at. No matter if it’s SMU, no matter if it’s another city or whatever, you know, they’re all an open book and they’re all open door. So, I would get to know that police department, get to know names, faces.”

SMU PD plans to implement new programs on-campus that will increase their visibility and personal interactions with students. This includes an Officer Affiliate program in the fall, which will assign a community officer to each residence hall and commons. They hope that students will eventually become more familiar and comfortable with campus police as a result.

“We need to probably do a little better job with the community activity, and we are doing that now. We’re launching several programs that we’re getting involved in, but also we need the help of the community to come in and, you know meet us halfway,” Captain Winn said. “We can’t operate, we can’t work without the help and support of not only the university but also the community as well. That’s a big part of it.”

At a recent diversity town hall, SMU PD officers, Black students, and recent alumni discussed how to address the current oversights in SMU’s diversity training and other initiatives. The students that the Daily Campus spoke with agreed with Captain Winn’s sentiment that both students and police would have to make efforts, but felt the police had a greater position of power and authority that gives them the responsibility and authority to initiate a better dynamic.

“I’ve heard about a lot of great programs that the SMU PD has had and interacted with, but with the majority of the campus,” Ford said. “I would definitely like for them to make a concerted effort to bridge that gap specifically within our own community because we’d be willing to take that step with them. But being the person of lesser power in this scenario, it’s very very difficult for us to reach out to PD. ”

Ben Nwokoye suggests that having police officers attend events and interact with the students outside of their uniform duties could help build a more positive connection between police and students of color.

“Not every student is going to be receptive to you [the police] talking to them when you have a uniform on,” Nwokoye said. “I feel like the biggest disconnect is…if you’ve never had an interaction with the police, your first reaction is probably going to be negative just because of everything you’ve seen on the media and stuff. So they should make active steps to try and paint themselves in a better light.”

For now, candid conversations like the ones initiated by the town hall and #BlackAtSMU are critical to creating a greater understanding on campus between students and officers.

“The biggest thing is face time…I don’t think PD has ever been proactive about getting out and solving the issue; I think they’ve been very receptive, and I think that’s where we can do better,” Ford said. “We need to give them that push that they haven’t been given…And I don’t consider myself a radical, but I think that a gentle nudge in the right direction would be good for us. I think that even an incremental change means that something good came out of all of this.”