Yuefan Hu, a first-year student from Nanjing, China, was hanging out with his high school friends at Zilker Park in Austin over the summer when a man approached them. That’s when the anti-Asian racism began.

“He told me ‘you Chinese people gave us COVID, and you’re hurting our country,’” said Hu, who moved to Texas two years ago.

His friends laughed along to relieve the tension, but Hu said he felt an overwhelming sense of uneasiness. He wanted to defend himself, but fear held him back.

“I can’t say anything because I’m part of the small population in the U.S.,” Hu, a business major, said. “People say that we’re taking their jobs and spreading like the virus. They show that they don’t care about you.”

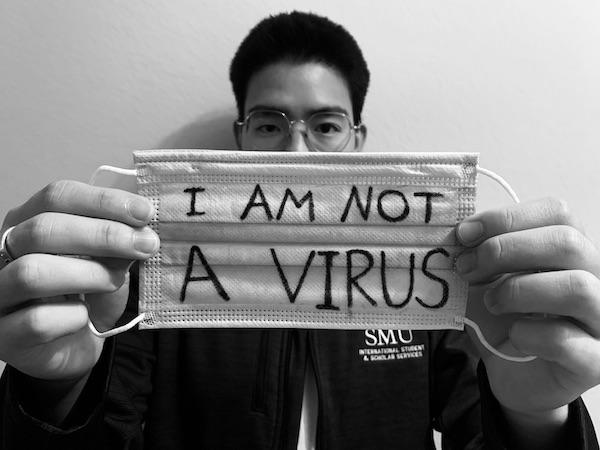

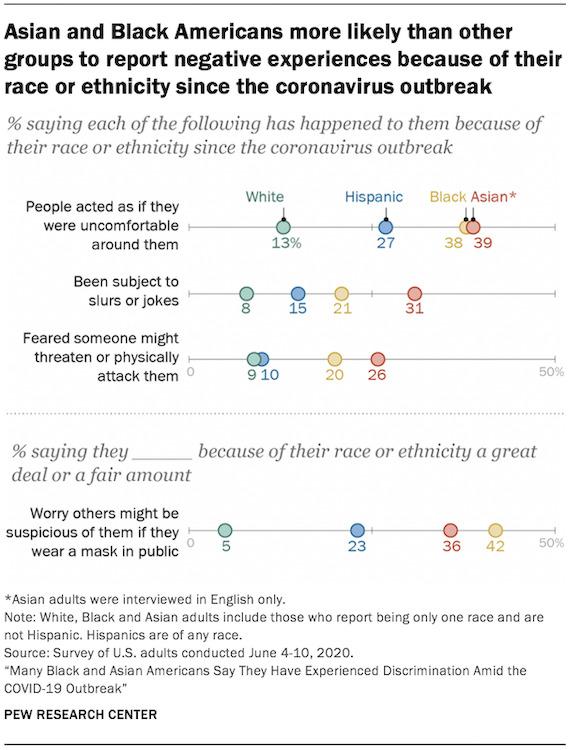

This incident is part of a bigger issue Chinese citizens living in America are grappling with: an increase in anti-Asian racism and discrimination due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

According to The Asian Pacific Policy & Planning Council’s initiative: Stop AAPI Hate, 2,583 incidents of discrimination against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders across the U.S. have been reported from March 19 to Aug. 5. Stop AAPI Hate was formed on March 19 in response to the increase in anti-Asian racism incidents because of the pandemic.

Some SMU students and faculty members say they have also seen a rise in anti-Asian racism and discrimination on campus. Senior Nikki Adams, who studied abroad in Suzhou and Beijing, China, during the summer of 2018, said that she faces discrimination for speaking Mandarin, even though she’s not Asian.

“Because I speak Chinese, people call me a Communist all the time,” Adams, who is white, said. “People have asked me if I’ve eaten dog before. I get the Communist comment all the time, and it makes me uncomfortable.”

However, Chinese student Maggie Qiu, who is from Shanghai, China, said she has never experienced discrimination on campus. She said some of her Chinese friends have faced discrimination, such as being blamed for COVID-19, but that she has always been treated with respect.

“Even in a class with all-white students, I’m really treated equally,” Qiu, who is studying accounting, said. “I had a professor who said that if we face any racial discrimination, then come to him to talk about it. I’m very grateful that everyone treats me equally at SMU, and everyone was very nice to me during the pandemic.”

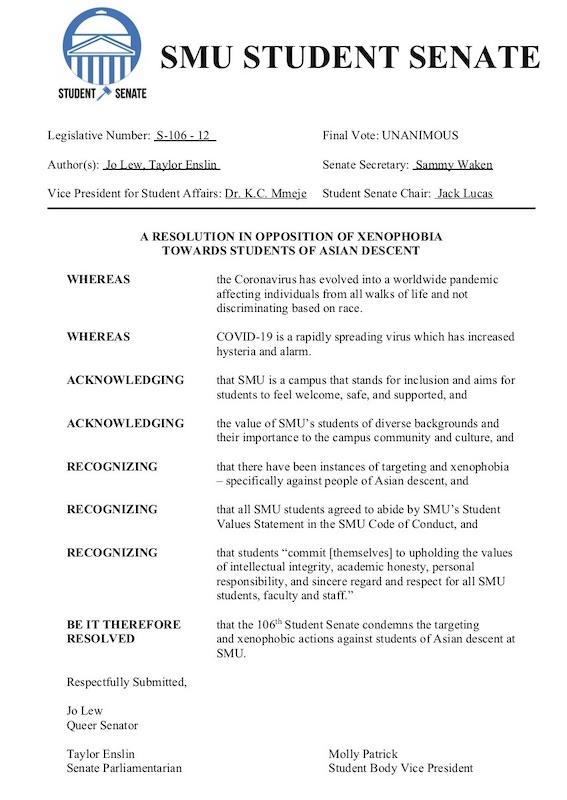

While SMU does not disclose information to the public about how many incidents of anti-Asian racism have been reported on campus, the university does offer services to help prevent anti-Asian racism on campus. This includes requiring employees to participate in harassment and discrimination training and offering counseling services to all students. This March, the Student Senate released legislation that condemned discrimination towards Asian students.

Junior Jeffy Xin, from Xi’an, China, said she has seen an increase in anti-Asian racism because of COVID-19. She said the increase is mainly because of how President Donald J. Trump refers to COVID-19 as the ‘Chinese virus’ and ‘Kung Flu.’

“The racism is because of Trump and what he says to the public,” Xin said. “What he says is really irresponsible and racist. Chinese people aren’t calling the H1N1 virus the ‘U.S. flu,’ so why is the U.S. government calling COVID-19 the ‘Chinese virus’?”

Adams, a psychology major, said that anti-Asian racism has been an issue on campus even before the pandemic and that she often hears stories about Asian students being called derogatory names.

“I was in a Zoom class and someone called COVID-19 the ‘China virus,’” Adams said. “I told him to stop calling it that and he said ‘Well, the Chinese gave it to us,’ and blamed it on Communism. He wouldn’t stop, even when I asked him several times to stop.”

Chinese language and culture professor Wei Qu, from Jilin Province, China, said President Trump’s rhetoric causes Americans to blame Chinese people for the spread of COVID-19. She said it’s difficult for Chinese citizens to speak up against anti-Asian racism because the Chinese culture teaches them to avoid conflict and maintain social harmony.

“For Chinese people, we think that suffering is a good thing and that it can help you grow,” Qu said. “So, Chinese people don’t speak up that much against anti-Asian racism. It’s just our culture. We don’t like conflict or fighting.”

Xin, a corporate communications major, said that she’s had to speak up against anti-Asian racism before and after the pandemic began. She said that being a Chinese student and having an accent causes American students to discriminate against her.

“I feel like I face discrimination because I’m an international student and I can’t talk the way that native speakers do,” Xin said. “When I’m in a group for a class, the Americans will be more friendly to each other than with me. Most Americans at our school are interested in international students, but don’t want to be friends with international students.”

However, senior Sarah Sedaghatzadeh, from Dallas, said many non-Asian students do consider how hard anti-Asian racism has been for Chinese students since the COVID-19 crisis began.

“I never realized the importance of reaching out to my Asian friends until I had an encounter with a student who was in tears telling me how they were stereotyped and treated poorly after the start of COVID-19 back in February,” Sedaghatzadeh said. “Inclusivity is one of the most important things we can do as students at SMU and we need to make our friends feel welcome here.”

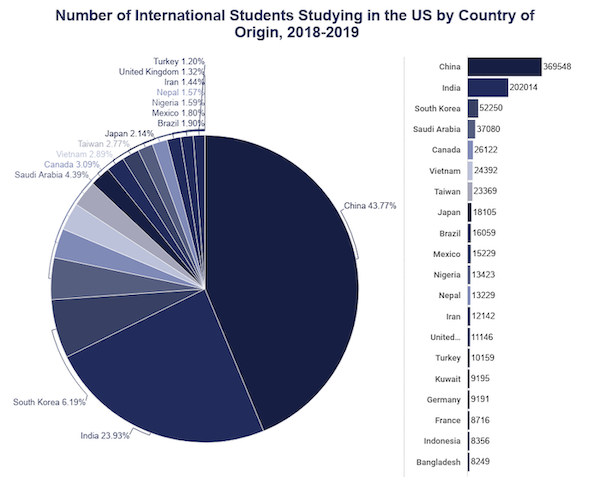

According to research done by Educationdata.org, international students from China are the largest group of international students studying in the U.S. In 2018, the U.S. economy made $14.9 billion from Chinese student enrollment.

However, Chinese international student enrollment has decreased since the COVID-19 outbreak. According to data from SMU’s International Student & Scholar Office, there were 802 Chinese students enrolled this fall, a drop of nearly 28% from fall 2019, when Chinese student enrollment reached 1,026. International students make up about 7% of SMU’s total enrollment.

Director of Admission Elena Hicks said that concern regarding COVID-19 in the U.S. has affected Chinese international students’ decision to attend in-person classes at SMU.

“In particular for international students, there are 3 popular options – request to study virtually this semester, or request a gap semester, or gap year,” Hicks said. “On the flip side, there are international students who, while still cautious, are grateful to be here in the U.S. and appreciate the strong infrastructure of medical services on campus and in Dallas.”

Although Chinese students, such as Qiu, feel that SMU does a good job supporting and respecting Chinese international students, other students believe SMU’s administration needs to take action to better protect Asian students.

“You can say whatever you want, but you need to actually do something,” Adams said. “I know SMU has a statement that says that they are against racism. Saying is easy, but doing is hard. SMU needs to do something.”