Dallas is no newcomer to the sex industry. Under the guise of so-called entertainment venues, clubs began to open up across the city in the 1920s, catering to the gangsters. The 1960s brought about a darker scene when underground strip clubs began to pop up in the industrial areas of Dallas. In 1977, the upscale sex club entered the picture when the Dallas Playboy Club opened on the second floor of what is now known as SMU’s Expressway Tower. The Playboy Club served as a large hub where wealthy Dallas men could kick back, ogle beautiful women, and drink endless booze.

Just four years later, and two miles north of the Playboy Club, sex industry entrepreneur, Don Furrh, would take the Dallas sex industry one step further by opening its first topless club – Million Dollar Saloon. The success of these two clubs fueled an industry that would thrive throughout the ’80s and ’90s and lead to Dallas’s current abundance of sexual entertainment: strip clubs, adult arcades, theaters, and peep shows.

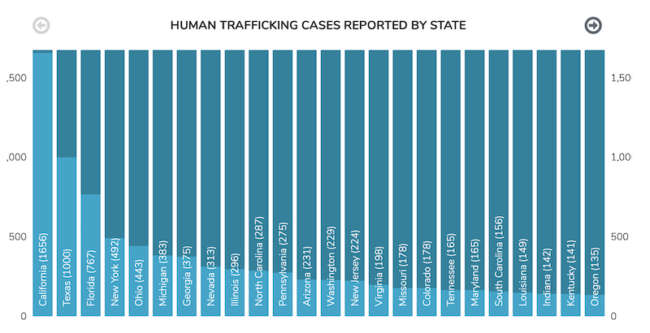

However, behind the deceptive glamorized outer layer of the industry lies the dark, and life-damaging, world of sexual exploitation and trafficking. In response, the Polaris Project was formed. This organization runs the National Human Trafficking Hotline and is the world’s largest, and leading, organization working to end human trafficking. Polaris Project defines sex trafficking as a modern form of slavery, in which individuals perform commercial sex acts through the use of force, fraud, or coercion. Furthermore, if a minor engages in commercial sex, they are automatically considered a victim of sex trafficking.

Rebekah Charleston, an anti-trafficking advocate and survivor, explained that there is a “happy hooker myth” in which the women working as prostitutes and in other areas of the sex industry are “white women who have other options, but they choose to do it.” While it may appear like this lifestyle is a choice, advocates, like Rebekah Charleston, say the sad reality is most women in this industry have no other option.

Trafficking is everywhere around the globe, but is often not considered an issue in the U.S., let alone in Dallas because it is disguised so well by the glamorized sex industry. People often view the participants in the sex industry as consenting adults, relishing in cash, choosing to be in their position. However, that is not the case because the vast majority in the industry are in it because they feel they do not have another option.

Teen runaways and girls, and/or women, who exhibit some type of vulnerability, or past trauma, are at the most risk of being sexually exploited. This was the case for Charleston. When she ran away from home as a young woman, she began dancing in Dallas clubs as a way to make money. The danger of doing this, or something similar, is that girls like Charleston find themselves feeling that they have no other options to make money to survive, leaving them vulnerable to being preyed upon and sucked into the life of sex trafficking.

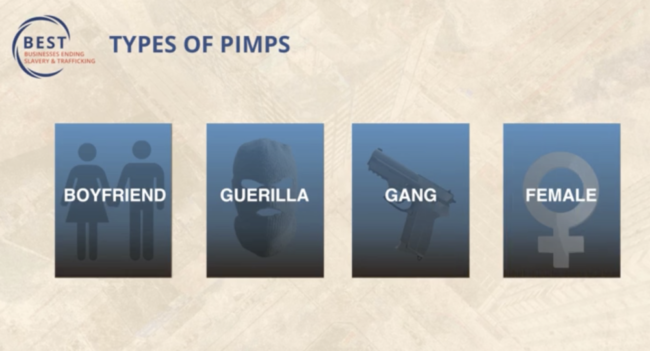

This happens because traffickers, also known as pimps, prey upon their victims within the same basic framework that Furrh followed when opening the Million Dollar Saloon. They, however, take sexual entertainment “one step further.” According to Charleston, traffickers will take a vulnerable woman who is already dancing in a club and will tell her something like “you are already dancing in the club, you will be doing the same thing just for a smaller group at a house,” and will then take her “one step further” into exploitation, continuing this process until she is eventually a full-fledged trafficking victim.

Treasures, a California based organization, works globally to bring awareness to the dangers within the sex industry and ultimately help women, who have been sexually exploited and trafficked. The organization has released a statistical report showing that 70% of females are trafficked directly from the sex industry. 89% of those women said they wanted to escape, but had no other means for survival. The report also shows that one in three women, who are working in sex industry clubs are doing it to pay their way through college.

The young women who are paying their way through college via the sex industry exemplify the vulnerability and desperation that traffickers look to prey upon. The women need fast cash and the industry can provide them with that. However, it can also lead them directly into the hands of traffickers, who will use false promises and the “one step further” framework to lure them into trafficking.

Another common way college-aged women make money within the industry is by being a “sugar baby.” A sugar baby is a person who receives cash, gifts, or other financial/material benefits in exchange for being in an intimate relationship, which often includes sex as part of the transaction. The paying partner is typically a wealthy, older individual, who has the capability of providing the sugar baby with luxuries, gifts, and larger payments.

Mosaic Family Services, Deputy Director, Bill Bernstein said that sexual exploitation and trafficking “is more hidden” on college campuses. Additionally, Bernstein explained that not only does the need for economic empowerment drive college girls to becoming sugar babies, but it also gives them a feeling of being in control. Sugar babies can control their schedule, determine who, and how many men, they will see. They also get the feeling of being desired by someone. College girls working as sugar babies blend in with the rest of their fellow students. However, sugar babies can just as easily be taken “one step further” until they lose the false control they felt they started with, which leaves them unexpectedly trapped within the world of trafficking as well.

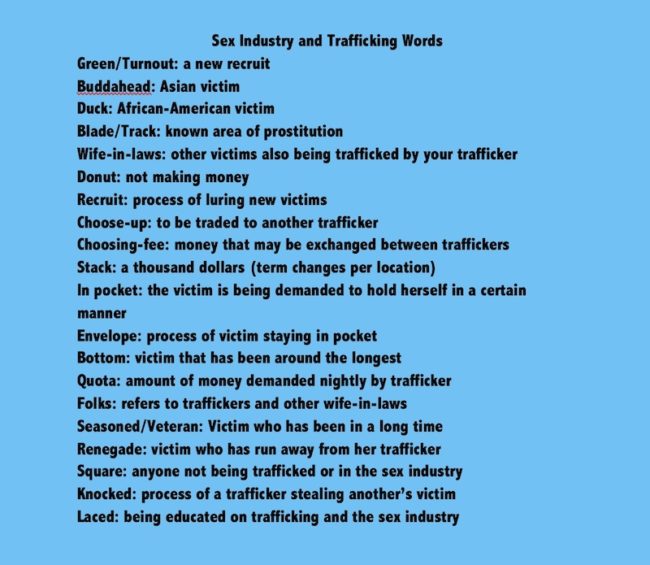

Because sexual exploitation and trafficking are hidden in plain sight, as they lurk on college campuses, recognizing indicators of the problem is crucial and has the potential to save one’s life. Charleston provided a list of sex industry words that are commonly used by victims and their traffickers. These words allow the ability to camouflage conversations without drawing unwanted attention. The list consists of 20 words, including but not limited to:

- Turnout: a new recruit

- Blade and/or Track: known areas of prostitution

- Choose-up: to be traded to another trafficker

Recently a survey conducted at SMU by myself, asked 65 students ranging from freshman to graduate students if they had heard the words. Students were provided with Charleston’s list of words and their definitions. The purpose of this survey was to research how many students had heard these words on campus. The results showed: 11.48% had heard the term “blade and/or track meaning known areas of prostitution,” 16.39% had heard the term “square,” meaning anyone not a victim; 14.75% had heard the word “knocked,” referring to the process in which a trafficker steals another trafficker’s victim; 9.84% had heard “wife-in-law,” which refers to victims being trafficked by the same trafficker; and 65.57% had heard none of the words in their context.

The survey’s results demonstrate that students may be hearing these words on campus, but they are hearing them out of context. While this might be the case in regards to common knowledge, it only takes a quick search on the popular website Urban Dictionary to find the sex industry definitions. Urban Dictionary serves as an online dictionary for slang words and phrases and is a popular search among college students. Because sex industry definitions are the first results to show on Urban Dictionary, this shows that it is quite accessible for students to hear, or at least find, the definitions of these words in their proper context.

Since exploitation and trafficking are hidden in plain sight on college campuses, it is important for students and faculty to be educated on the words, their definitions, and context. If these words are recognized, it could help save a woman from the sex trafficking industry.

Along with recognizing the significance of sex industry words, nonprofits like DeliverFund and Mosaic Family Services share a goal of advocating for sex trafficking awareness. These organizations focus on the importance of reporting suspected trafficking and how to do so in Dallas.

DeliverFund’s founder and executive director, Nic McKinley, explained that once people become aware of trafficking, they want to devise some heroic way to come in and stop it. The problem is that “if you do not have a badge or gun, you cannot stop it.” According to McKinely, if someone other than law enforcement was to go in and physically take that person away, it would be considered kidnapping. The process takes time and the victims who leave should have “left on their own free-will.”

McKinley further explained that there is a common misconception, people think that nonprofits are the ones doing the saving, but they are not. The nonprofit’s main role is to aid victims in their recovery process, advocate for awareness on the subject, and serve as a buffer between law enforcement and the everyday person wanting to fight trafficking.

Nonprofits and other anti-trafficking advocates work to promote awareness by educating people on recognizing trafficking. A compilation of trafficking warning signs provided by Charleston, DeliverFund, and Mosaic Family Services are listed below.

- Someone who suddenly has many luxury items: This is especially important if it is known that the person in question could not previously afford said items.

- A person who does not seem to have control over their schedule: This might look like someone who cannot make time commitments, and/or consistently fails to show up or follow through with plans.

- Bruises/swelling

- Carrying prepaid credit cards

- Carrying large amounts of cash and/or rolls of cash

If there is the concern of imminent danger, 911 should always be called; otherwise, suspected trafficking should be reported to a hotline. Mosaic runs a 24-hour hotline, serving as a buffer between law enforcement and the community. The hotline generally receives two types of calls, each with its own follow-up process.

- The caller is a trafficking victim: law enforcement will be notified and Mosaic will arrange to provide them with immediate help

- The caller is a concerned citizen suspecting trafficking: Mosaic will inform law enforcement and an investigation will take place.

Recognizing the signs of trafficking and reporting it could save a life. If someone feels that they see the signs of trafficking, they should not hesitate in calling either the National Human Trafficking Hotline or the Mosaic Human Trafficking Hotline.

National Human Trafficking Hotline: 1 (888)-373-7888

Mosaic Family Services Human Trafficking Hotline: (214)-823-1911

This article is part of a series in a special project on sex trafficking in North Texas from an SMU Division of Journalism course titled Human Rights and the Journalist. The class is taught by Michele Houston.