Travis Nolan crouches over a ping pong table, lights hovering over his shoulder. Progressive metal music plays softly in the background. Each crease he makes in a piece of ultra-thin paper is strategically folded to ensure a perfect outcome.

He easily holds a conversation as he makes crease after crease like he has done thousands of times before.

“It’s a space where I feel like I know what I’m doing. Or if I don’t know what I’m doing, I’m confident that I can figure it out eventually,” Nolan said.

Nolan gets quiet as he comes to a complicated fold, holding his breath to make sure the paper doesn’t rip.

At the age of 7, Nolan’s dad taught him how to fold an origami goose and he became enticed by the art of origami. After receiving “Origami Design Secrets, Second Edition” by Robert Lang as a gift, Nolan became enamored with creating original pieces. Using origami as his escape from the everyday stress of class and life, Nolan finds solace in spending hours working on complicated origami designs.

“Some of the origami is stressful,” Nolan said. “You’ve been folding this sheet of paper for 20 hours and now you have to do some complicated maneuver. Is it gonna rip? But a lot of times, it is really calming.”

Nolan is a sophomore studying biology and geology. His goal is to work in paleontology after graduation. When he is not creating new origami designs, Nolan is digging up fossils with the Whiteside Museum of Natural History in Seymour, Texas. He has been volunteering with the museum since it opened in 2013 and is working on a research project with them this summer.

In the 2021 International Origami Internet Olympiad, Nolan placed fifth overall and helped the USA team rank third. This put the USA on the IOIO leader board for the first time since the competition was founded in 2011. Nolan exceeded his goal of making it into the top 20 and received two gold ribbons for his work.

For his winning design, Nolan pulled inspiration from his other passion: paleontology. The final product was a complicated 500-million-year-old predatory shrimp called the Anomalocaridids, an extinct relative of modern arthropods.

He has even met other origami enthusiasts, like Catherine O’Mary, at a geology convention. While not everyone Nolan has met through origami has become a friend, he appreciates the connection that everyone has.

“Origami connects people by speaking to their sense of curiosity,” O’Mary said. “It’s a natural sharing of ideas and mechanics.”

O’Mary describes Nolan as eccentric and a quick learner. He specializes in 22.5-degree designs that restrict the folds of the design to multiples of 22.5 degrees. Because Nolan is self-taught, his projects are often odd and part of a discovery process. Nolan is inspired by the fossils he researches in his digs and models his designs after them. He looks at each new project as a puzzle that he is trying to solve, starting with a particular part of the animal that he wants to perfect.

“[Fossils] are actually really important for understanding evolutionary history in general, and particularly the evolution of mammals and humans,” said Nolan.

In 2017 Nolan created an origami organization in Dallas and asked O’Mary to be the vice president. They got involved with Paper for Water in 2018, an organization that sells origami and donates the money to World Water Crisis. Currently, Nolan is trying to start an origami club that volunteers with Paper for Water at SMU.

Through origami, Nolan has had many opportunities to showcase his work. He has led folding nights at the Perot Museum, created designs for a book cover, and even interviewed for a craft competition show in Los Angeles. One of Nolan’s favorite memories is when Origami USA offered him a scholarship and flew him out to New York for their annual convention. During finals week of his freshmen year, the 9th Street Art Gallery in Wichita Falls showcased his work at an exhibition for two weeks.

As Nolan continues to fold, he describes different papers and tools he uses in his work. He is unhappy with the cheap craft paper that he is working with but notes that it is good for practice or prototypes. Nolan typically works with larger sheets of high-quality paper that can get up to 3-4 feet in length. He never works with rulers. The creases are supposed to be established by folding not measuring, he says.

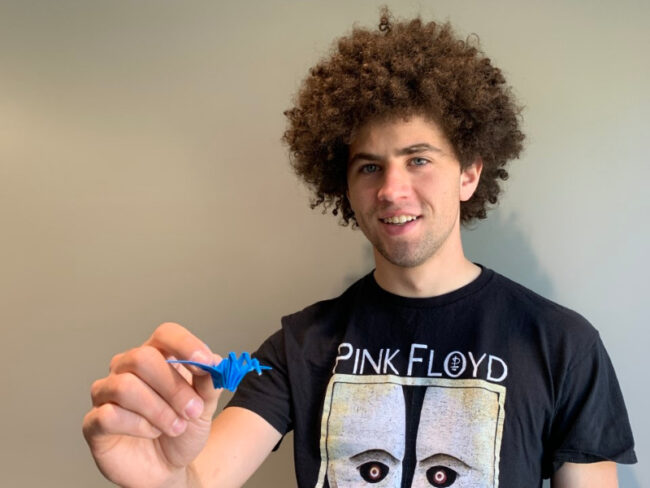

Nolan stops talking and makes a few quick folds. He looks up and presents an intricate blue three-headed swan.