Part two – ritual

(This is the second column in a series)

Rituals are the processes we repeat and expect. We the living. Often rituals are about the dead, even the very long dead.

While digging this summer at the Chaves/Hummingbird site, a long-ago abandoned pueblo, I again came to a human burial. It was my second. Last year, while excavating a room on the main mound, I uncovered what I first thought was a gourd. There was little chance a buried plant, such as a gourd, would survive those hundreds of years.

Still, it looked and felt and sounded like an old, stained gourd.. The sutures of a skull alone showed it was much more.

The skies began to grow darker as the skull was exposed. The rain threatened and then fulfilled its threat. We covered the trenches and rooms we had excavated with tarps and retreated to the security of the quonset hut. I put sifted sand over the skull to protect it and tarped the room reluctantly. The only record of the skull would be my drawings and I would have preferred to finish in a single setting. The weather would not allow me that pleasure.

The rain came in torrents, wind carrying it furiously and often horizontally. During one of the quiet moments right after dusk all but a few of us headed for sanctuary in town. The dirt road had turned to pudding and only a few of the four-wheel drive vehicles could get out to the highway and into the security of a hotel. The few that stayed pushed and tied towropes. We danced in the mud and rain to “Magic Bus” playing on the radio of the lead vehicle.

We watched the tail lights disappear as we danced in rain-soaked darkness and then hiked back to the lab.

The wind had died by the time we reached the lab and the rain had abated to steady patter on the metal roof. The patter was soon accompanied by the faint croaking of frogs. The frogs that had been hiding, dormant, inches below the surface, had been woken from their slumber by the onslaught of water. Their alluvial cue freed them to feed and breed quickly enough that their offspring would have time to dig and hide below the earth’s surface before it dried up hard again, imprisoning them until the next monsoon.

I don’t know if they were chasing the lights in the quonset hut or the bugs that chased the same light. Either way they hopped en mass toward the open bay doors. Hundreds of frogs the size of poker chips came hopping to us.

First a few, and we tossed them back into the darkness. Then waves of frogs began to flow out of the night forcing us to turn out the lights. The next day little rattlesnakes began to emerge in pursuit of the now abundant prey (but that’s another story.) The monsoon had again set in to motion a number of processes in a mad rush to reproduce. The processes in action had and should continue across time. The rituals are human.

I was uncomfortable referring to the remains as “it” or “skull” or “remains.” From what little we could see sex could not be determined; never the less, I called him Karl after Karl the Hammer, Charlemagne’s daddy. The name seemed fitting for the wrath the monsoons had unleashed upon us.

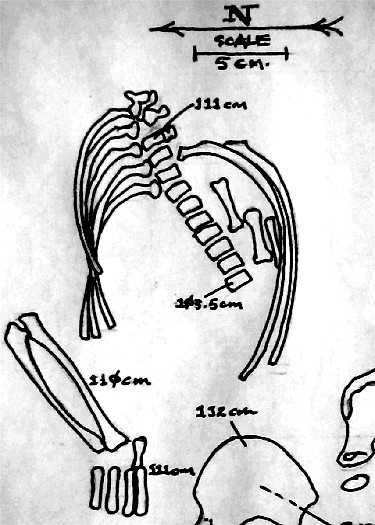

Rules (legal) of the moment, passing as the pendulum of politics, prohibited excavation and discretion prohibited photographs. The next day I hid from the occasional hot sun under a mylar canopy (my colleagues jokingly accused me of sleeping) and documented what little bit of Karl that had been exposed. On the second morning after discovering him I finished. I covered him with sifted sand and a protective layer of stones.

For the living, the process was not complete. The weather was coincidental but the foreboding feelings seemed to match the gray skies. I burned sage gathered from the mesa as we back-filled that portion of the excavation. The sage I used grows all over the area. The smoke is sweet, soothing the senses and the spirit.

I say the ritual was not for Karl, or whoever he may really have been – he had long since passed away. It was for us. Nevertheless, the clouds parted within minutes and the sun shone down on our soggy pueblo. Within days the desert was thick with green and then burst into bloom.

The field season was over a few days later. The roads were dry and I drove out early one morning on my motorcycle.

About a mile before the ranch gate an owl swooped down from behind me. He continued, slowly, just a few feet in front of and above me, painting the sky with his wing tips. He led me the last mile away from the site and then turned and effortlessly glid back toward the mesa.

To some an owl’s visit is an omen of death. I had no worries about the long drive home or myself. I had no worries of death at all.

The owl, the wind, the rain, them bones were all omens. Reminders of mortality and of rebirth. Right there, again, I questioned my own significance or even relevance. The owl reminded me I was not alone.

The next discovery of a burial came this year.

Part two – ritual