Music and dance paint vivid view of history

Rather than dipping her quill in ink to chronicle Mexican history, Amalia Hernandez captured it with dance.

On Thursday, Hernandez’s Ballet Folklorico de Mexico celebrated 50 years of documenting events from pre-Hispanic rituals to the Revolution of 1910.

With music as parchment and swirling skirts as pen strokes of Mexico’s dramatic history, nine dances traced the Mexican spirit more successfully than any dry historical text.

Although the performance was an enjoyable feat to be admired for its complexity and spirit, it was a bit uneven. The subtle timeline of history the first half traced lent consistency and cohesiveness. The second half lacked both of these.

Further, nothing can match the infectious mood a skilled mariachi can inflict; without live music, some of the dances suffered.

“Los Matachines” opened the evening with a nod to both the indigenous peoples of northern Mexico and 16th century Spanish influence.

Although it began as a dance performed exclusively during religious celebrations – as a custom of “dancing with one’s gods” – the dance evolved into a form of praise for Christian dieties.

Because the performance was more rhythmic than graceful, it was a bit jarring. The raw beat (sans trumpets or stringed instruments) and scarce costumes provided a link to a lost and primal past.

“Tunes of Michoacan” and “The Tarima” returned the audience to its expectations of traditional ballet folklorico.

Women seemed to be perfectly coiffed dolls: eyes, hair and dresses moved in unison. They were, by turns, pastel confections twirling in tasty pirouettes, and then blooming buds boasting yards and yards of vibrant material and joy.

In crisp white suits and delicately tipped white cowboy hats, men were marionettes with impossibly precise movements.

One almost strained to see the strings that must have been controlling the perfectly timed, deft motions of the identically dressed dancers.

After the closing strains of the mariachi music and last light steps of the village life, the story of the Revolution of 1910 danced onstage.

Swathed in shiny and close-fitting European finery rather than generous pastels or vibrant primary colors, Mexico’s upper crust danced polkas and flirted as mariachis wearing large sombreros entered and stood on one side of the stage.

The division between the two classes could not have been more obvious: the Revolution of 1910 was a battle for the freedom and rights of those unfortunate enough to be born without money. (The revolution proved to be a catalyst for sweeping social change.)

Tension between the two classes increased as one mariachi made eyes at one fine lady; her dapper cohort eventually chased the lowly musician off stage.

Finally, a group of revolutionaries entered the “drawing room” of the dandy aristocrats, and the Revolution began.

With the famous tune “Adelita,” behind them, female revolutionaries charged in with bullets strapped across their chests and performed in linear formations.

Brandishing guns and dominating the stage, the women accepted a place in Mexican history and provided the most climactic performance of the evening. Their spirit and dedication made the dance a thrilling experience.

This ballet was dedicated to the “Soldaderas,” women who “fought next to their men and even bore arms.”

Though the “Festival in Talacotalpan” proved less inspirational than its predecessor, the dance was sufficiently imaginative to distract its audience from boredom.

Surreal costumes, called “Mojigangas” were huge figures “representing the lives and legends” of the village of Talacotalpan. The characters, including an oversized fish, clown, dark skinned angel, devil and weeper, were grotesque.

Because there is no substitution for live music, the second half of the performance lagged considerably.

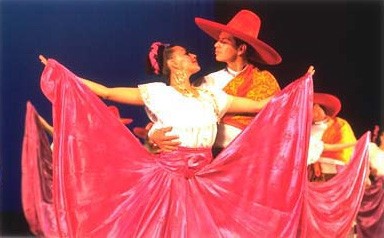

Of the four remaining dances, two subsisted on recorded music. “Guelaguetza from Oaxaca” was a pre-Hispanic selection inspired by the ancient Zapotec custom of offering a welcome “through the language of music and dance.”

With drama reminiscent of a soap opera, “Wedding in Huasteca” picked up the musical and emotional pace by telling the tale of a groom en route to his own wedding.

The groom resists everything but temptation and ends his walk in the arms of a beautiful Indian woman. Even as he woos his Indian love, his bride toys with the affections of another villager.

Eventually, the bride and groom reunite and the village rejoices – but not before the beautiful Indian crashes the party and the rejected suitor is murdered.

One can say little about this performance besides noting the costumes. In the shorter, more casual skirts of the village dress, the dizzying footwork of the women can finally be appreciated.

“The Deer Dance” captured the tradition and culture of the Yaqui people – the only aboriginal tribe of Mexico who resist both racial intermixing and exposure to modern culture.

The result was similar to the previous pre-Hispanic offerings – a raw, intense beat behind a solitary dancer is an event one can see only so many times.

By the end of the “Deer Dance,” only one dance could get the crowd on its feet: the “Jalisco.” The performance ended in triumph – to the tune of three standing ovations – after the dance.

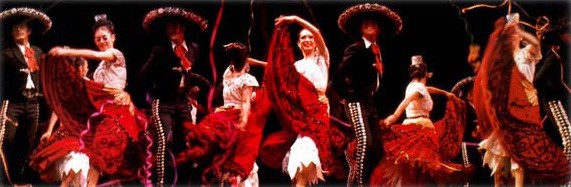

This dance defines the term “crowd pleaser.” In marched the mariachis, in swirled, twirled and whirled the brilliant scarlet, gold, fuchsia, and royal blue skirts of the women and in sauntered the men, sharply dressed head-to-toe in black.

This is “El Jarabe Tapatio,” or the “Mexican Hat Dance” and nothing but a personal experience can convey the lavishness, the sensuality, the spirit and the joy of the music and dancers as they perform.

“La Culebra” and “La Negra,” two very familiar and famous tunes, were applied as a medley to keep the dancers on their toes and keep the audience out of breath.

In a performance where color, music and movement are meant to capture what words cannot, Ballet Folklorico painted a beautiful picture of history.

Music and dance paint vivid view of history

Music and dance paint vivid view of history