Beep, beep, beep, 6 a.m. the alarm is screaming and so is Jane’s stomach.

With daybreak comes hunger, that inevitable, insatiable hunger, and those growling thoughts. Self-loathing anxiety screams imperfection from inside the mirror as Jane Jemerson walks past towards the scales, the true test.

Numbers don’t lie.

“I used to weigh myself in the morning and sometimes in the evening,” collegiate distance runner who we’re calingl Jane Jemerson states. “Even if I knew that the daily changes doesn’t [sic] even have anything to do with real weight gain or loss, it affected like my mood and my decisions the whole day.”

The number was the baseline, the preliminary data for the day, it was the master of all thoughts, the pretext to all decisions, the veil like filter that distorted reality and only allowed perfection in its raw statistical form to perpetrate. For two and a half long years Jemerson suffered behind this veil of flawed perfection as she ruthlessly forced unattainable excellence in every aspect of her life.

Her sport. her education. her relationships.

And her means of accomplishing all of these things – her body. Jane’s body.

Because if this was perfect, so too would be everything else.

The pressures caused by female objectivism among college-aged women is a well-documented phenomenon, but perhaps a more taboo topic is the amplification of these issues driven by the target-oriented perfectionism witnessed in high-performance collegiate sports.

“The culture within athletics, where … an over-emphasis on the connection between weight and performance occurs,” says, Ph.D., Licensed Athletics Psychologist, who doesn’t want her name used due to patient confidentiality . “Places athletes at a higher risk for developing eating concerns than their non-athlete peers.”

25 percent of college-aged women engage in bingeing and purging as a method of managing their weight, according to The Renfrew Center Foundation for Eating Disorders, 2003 summary of ED statistics. While in his book “I’m, Like, SO Fat!” Neumark Sztainer, D states 50 percent of students aged 18- to 25-years-old will actively engage in unhealthy weight loss mechanisms at one or more point during college.

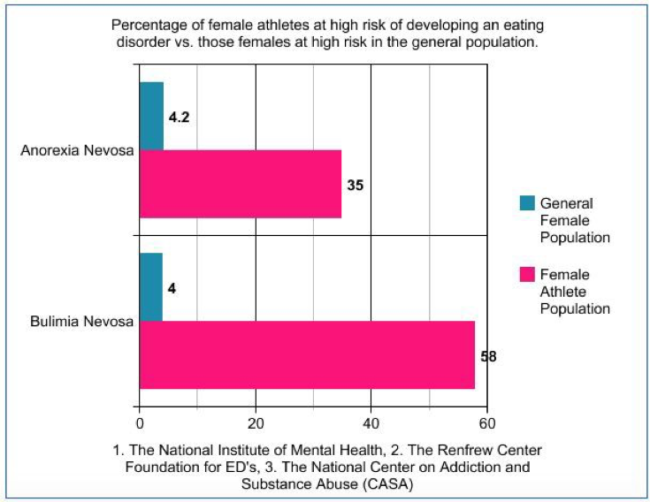

For collegiate athletes the pressure to perform at a peak level on a continual basis while still achieving in the classroom, puts 1 in 3 female athletes at direct risk of forming a serious and sustained eating disorder according to the sports documentary “Why Don’t You Lose 5 Pounds?” produced by Olympic figure skater Nancy Kerrigan.

These risks are further enlarged for those competing in aesthetic and gravity oriented sports such as Gymnastics, Distance running, and Dance, with Renfrew Center Foundation statistics displaying 42 percent of female athletes in these sports practicing disordered eating.

Jemerson, like most athletes, is highly analytical. A great quality when taken in the ideal situation, but the reality of the student-athlete life is far from ideal in terms of the time deficit juggling multiple priorities presents. Evidently, the most important ingredient to athletic success – adequate recovery, tends to fall last on ‘at risk’ athlete’s lists.

Athletes are programmed to evaluate their performances, forming links between previous actions and performance results.

Ron Thompson, a consulting psychologist for Indiana University athletics and co-director at McCallum Place, said. “This emphasis on reducing body weight/fat to enhance sport performance can result in weight pressures that increase the risk of restrictive dieting, as well as the use of pathogenic weight loss methods and disordered eating,”

Over attributing performance outcomes to nutrition and specific food groups can further create extreme and divisive thinking.

“I have seen clients that [sic] use ‘black and white’ or ‘all or nothing’ thinking when it comes to food groups,” PhD, Licensed Athletics Psychologist, said. “These thought patterns can lead to feelings of guilt or shame that come when eating self-identified ‘unhealthy’ foods.”

Jemerson remembers directly linking good foods to good races and bad foods to bad races. She applied strict rules, always plotting to avoid situations with ‘bad’ foods.

“Afterwards I felt guilty,” she said. “If my plan … did not work out, I was kind of in a ‘now it doesn’t matter anymore’ position and just completely over-ate.”

Like Jemerson, high school distance runner, Lisa Smith, has experienced the shame and guilt associated with ‘good’ and ‘bad’ foods first hand.

“Whenever I felt too full I would always feel guilty and then think about how this would affect my training, and my long-term performance goal,” Smith said. “Carbs were the main food group I couldn’t handle, it was just a red flag straight away.”

Stereotypes and the need to be in control of athletic success also played a role in Smith’s irrational nutrition.

“Have you ever seen a chunky distance runner win a race? Never,” she said. “It’s always the stick skinny ones that win, so with that in mind I thought the only way I could have a good season running would be to lose some weight.” – Lisa Smith

Restriction is not the only eating disorder faced in sports, in fact, according to the The National Institute of Mental Health, the high energy output of sports sees Bulimia Nervosa assume a close second place in those illnesses gripping female athletes.

For Smith, the extreme guilt escalated beyond thoughts to counter actions .

“In situations where I couldn’t avoid eating main meals, … I found myself eating as quickly as possible and then looking for an out,” she said.

Bulimia held Smith in its grasp for nearly 2 years.

“It really ate me alive,” she said. “It’s so much more of a mental game than just restricting. You find yourself hating yourself for a lack of discipline.”

Giving into hunger was Smiths’ worst fear. She feared the guilt that came with overindulging and the secondary self-hate that came as she forcibly made herself sick.

“The worst part is when you’re really trapped by the disease you tell yourself this is the last time,” she said. “But you know later the same day or the following day you will be doing it all over again.”

Forging a path to recovery and acceptance wasn’t easy, “I felt bloated with heartburn all the time,” she said. But finding appreciation and love for her current body and food has helped.

Smith now recognizes it was a combination of low iron levels, depleted micronutrient stores, sleep deprivation, and inadequate fueling that hindered her athletic ability, not the ‘extra’ weight she deemed too much.

Both Jemerson and Smith fell victims to their illnesses through an individual determination for perfection. With these illnesses still holding stigma in many sports, how does a team environment and atmosphere alter such behaviors? And how do these behaviors alter the social environment they partake in?

Feelings of both shock and upset riddled graduate student and distance runner, Marlene Gomez, when she first encountered a struggling teammate purging.

“I couldn’t handle the fact that someone would deliberately throw up in order to decimate intake of calories,” she said. “I wanted to grab her shoulders and shake her, tell her that this isn’t something she needed to do but I couldn’t.”

Knowing she didn’t have the skills to directly help in the moment, Gomez sought higher support from coaching staff.

“It is uncomfortable to ask someone ‘do you need real help?’” Gomez said. “But sometimes there needs to to be very uncomfortable and brutally honest conversations in order to facilitate healing.”

The recent movement from stick thin to strong girls dominating social media stereotypes seems to show society is on an upward turn. But for athletes who justify under-fueling as a means of nutrition to better perform, the underdiagnosis of sports-related eating disorders continues to grow.

Masked under washboard ABs (Abdominal Muscles) and the media’s infatuation with #FITSPO, #GAINS, #STRONGGRILS. Athletes find it hard to fit within both the strong and lean stereotype.

These society imposed expectations and labels make it increasingly hard to identify and help those who desperately seek it, Ph.D., Licensed Athletics Psychologist, said.

Attempting to reach out and offer help in this media-saturated environment creates a sense of helplessness for those close to the athlete.

“You feel helpless because it seems impossible for the person to break their cycle,” Gomez said.

You worry about them, and about the influence, their situation can have on other athletes who might be tentatively struggling with their own performance and body issues, she said.

“In general, I hope just communicating on a more meaningful level rather than a superficial one helps,” Gomez said.

For Gomez, fully accepting her own body rather than comparing it to others allowed her to find grace early on in the sport.

“Our own bodies matter,” she said. “Not how they compare to others’.”

Recovery is not a quick fix and for many who experience eating disorders within athletics, personal thought patterns and body acceptance can remain distorted.

“It was hard because I was still in a sport in which you have to be pretty lean,” Jemerson said. “But I realized for myself that … being lean and strong does not mean I have to be like skinny … I shifted my focus from … being skinny and not eating to being fast, and you can only be fast if you … fuel yourself.”

With a commitment to holistic health both Jemerson and Smith have been able to see beyond their eating disorders and forge a happier lifestyle going forward.

“It’s … a mindset to feel happy with yourself,” Jemerson said. “If you look in the mirror and you are telling yourself that you are proud of your body and what it does for you every day you, … will feel so much better.”

Determination and an utmost will to succeed is seemingly one of the largest factors that pulled Jemerson into her eating disorder, but Ironically with a change in perception and a commitment to something more than numbers and object ridden goals, this same mentality was the agent of change that pulled her out, to a happier, healthier lifestyle.

“It’s actually pretty similar to running or athletics in general,” Jemerson said. “If you … go into a race with the mindset to lose, you will lose. But if you are telling yourself that you can do this, you are unstoppable … No matter how many tears, sweat and pain recovery may cause, it is so worth it.”