She reached for the carton of milk but her hand had only brushed against the cardboard when it happened.

“First my ears were ringing,” sophomore Krissy Orth said. “I started seeing black dots everywhere, and a rush of heat filled my body.”

Orth was making a bowl of cereal for breakfast when she had her first POTs episode. Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome, POTs for short, is an autonomic nervous system disorder that affects the circulation of blood flow.

“I passed out on the floor and my host dad found me shortly after,” Orth said. “I had to skip school that day cause my whole body was weak and I was throwing up.”

Orth is one of many people affected by chronic illness. The National Health Council reports that about 133 million Americans, 40 percent of the national population, have an ongoing, chronic illness. And by 2020, that number is projected to grow to 157 million. These often “invisible” illnesses affect many people on a large scale, but also many people on a scale as small as a college campus.

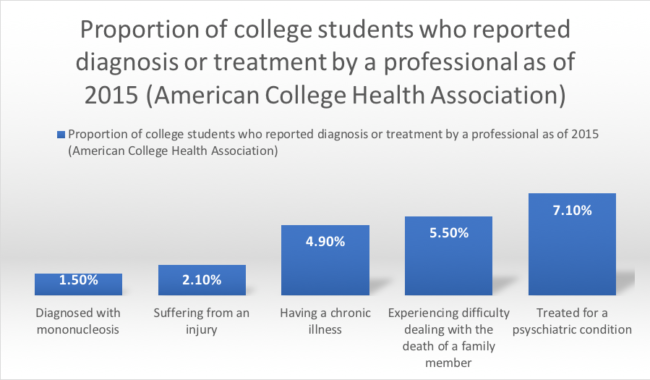

https://www.acha.org/documents/ncha/NCHA-II_WEB_SPRING_2015_REFERENCE_GROUP_EXECUTIVE_SUMMARY.pdf Photo credit: American College Health Association

The Assistant Director of Health Promotion, Griffin Sharp, believes that the biggest difficulty with these invisible illnesses is miscommunication and a lack of information on what these chronic illnesses entail.

“I think to combat these difficulties, it’s best to educate ourselves on chronic illnesses,” Sharp said. “What works for one person might not work for another person, even if they have the same chronic illness. So, it’s really important to work with those individuals, to best understand how they manage their chronic illness and how they can best be supported by those around them.”

Junior Kayla Keck was diagnosed with Celiac disease in her senior year of high school. Celiac disease is an autoimmune disease in which eating gluten causes damage to the small intestine.

“All my friends know I’m gluten-free just because I’m so active about it,” Keck said. “But a lot of social events are surrounded by food.”

Keck said that while at first, she was worried she would no longer be able to eat some of her favorite foods, she has sought out to learn more about Celiac and substitutes for the non-gluten-free foods she sometimes craves.

“I was sad then, but I realized I eat pretty normally now because I find a lot of substitutes and I go out of my way to find the substitutes,” Keck said.

Keck believes education is extremely important when it comes to chronic illnesses, especially those that are considered invisible to the eye.

“A lot of professors don’t really understand it’s an actual disease and not just an allergy where you get over it the next day,” Keck said. “Celiac takes a few days, or a week or two, to get over a reaction.”

Orth echoes this, saying POTs had a huge effect on her upon diagnosis, especially in terms of social life and academic life.

“I was making stupid mistakes in school, such as accidentally taking home a test instead of turning it in at the end of class,” Orth said. “I was always an A+ student, but all of a sudden I was struggling in school.”

Because POTs is an “invisible” illness, other people are not always aware of how disruptive its symptoms can be.

“My friends sometimes make fun of me when I am feeling symptoms or say that I can’t go out or do something because of my POTs,” Orth said.

Although there is not a cure for POTs, a combination of medications can treat different aspects and lessen symptoms of the illness.

“For example, I take separate medications for low blood pressure, migraines, ADHD, and anxiety/depression,” Orth said. “At one point, the doctors didn’t know exactly how to treat my symptoms so I was on 8 different medications for a while.”

Orth said that SMU has been very helpful in making accommodations for her illness, DASS (Disability Accommodations & Success Strategies) has given her extra time for test-taking, flexible attendance and priority enrollment.

“My specific advisor was super empathetic towards me and was very knowledgeable about POTs because her daughter has the same condition,” Orth said. “When choosing colleges, SMU became one of my top choices because of how small the campus is and the fact that class sizes are not huge compared to other state schools.”

Sharp says that SMU aims to work with the students, making sure they are properly adjusting to campus life and communicating with their parents to make sure they are completely aware of everything going on with their child.

“I think SMU does a great job of making sure students with chronic illnesses are supported on both an academic and medical level,” Sharp said. “SMU’s really great at communicating with students who might need accommodations and communicating with professors and faculty members on whether or not a student might need extra support.”

Additionally, the health center’s pharmacy is full-service and located right on campus for students to pick up medicine at their convenience.

“Here in the health center, our doctors are very well-versed in all forms of chronic illness and most campuses do have it, but we have a very good medical staff here that works with the students with chronic illnesses to make sure they are managing it appropriately,” Sharp said.

Orth thinks that it is important to be exposed to strong resources, like the ones SMU provides, especially when dealing with a long-term illness. She has come a long way from her first encounter with the illness to her official diagnosis 6-8 months later.

“I have always been a hard-headed, do-it-myself and don’t seek help kind of girl,” Orth said. “However, after realizing that my body and brain don’t function the same as everyone else, I learned that sometimes you need to ask for help in order to be on the right track.”