by Reece Kelley Graham

There he was, standing on the sideline — and nobody recognized him.

Unshaven and wearing cargo shorts with a button down shirt, Lance McIlhenny stood watching SMU’s scrimmage, covering his full head of salt and pepper hair with a towel while squinting through the Texas heat.

Inconspicuous, but not purposely, McIlhenny watched as head coach Chad Morris put his Mustangs through specific in-game scenarios.

Some SMU players may have met McIlhenny before, but most had no idea of the man behind the hand they were shaking. Nobody would blame them – he had played his final snap for SMU well before any of the current Mustangs were born.

As he walked back up the stadium stairs near the end of practice, I turned to a group of reporters and asked, “Did y’all see Lance?”

“Who’s Lance?”

“Lance McIlhenny,” I added, thinking the unmistakable last name would jog their memories.

“I’ve heard the name,” another reporter admitted, “but who is that?”

I share this moment not to shame my colleagues, many of whom are young alumni like myself.

I share this moment, rather, because it’s the perfect example of how one might react when they hear the name Lance McIlhenny – I mean really, the name certainly isn’t common, but who is Lance?

He’s the greatest SMU quarterback you’ve never heard of.

That is, unless you lived in Highland Park during the late ’70s and early ’80s. In the Park Cities, the name McIlhenny is a household name, an instantly recognizable mainstay. A name celebrated for its ability to transport memories back to when times were good.

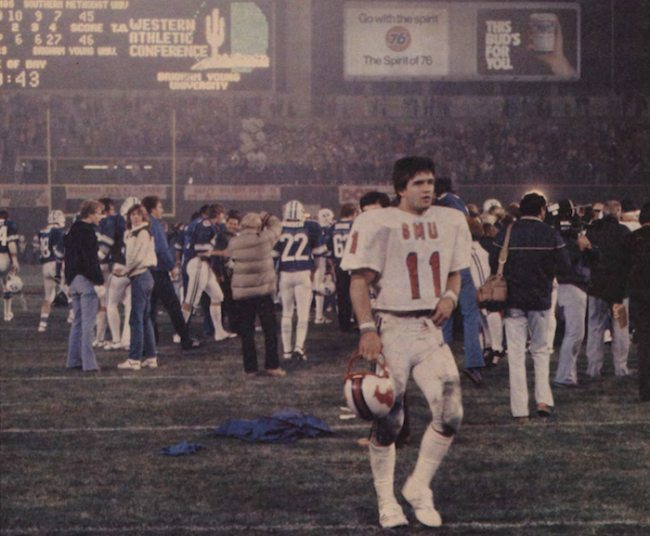

Everywhere else, Lance’s legacy has been forgotten – a story buried deep within the greatest and arguably darkest chapter of SMU football history.

When people off The Hilltop hear the name, “Southern Methodist University,” they think of words like “money” and “scandal” — words that are frequently intertwined.

They also think of a great academic institution, known for its clout and history of throwing it around.

Mind you, that’s all just perception. That’s how one might perceive SMU and its football program if they gathered their information exclusively from Thaddeus Matula’s 30 for 30.

The documentary entitled “Pony Excess” tells the story of SMU’s program receiving the “Death Penalty,” largely from the perspective of the media.

The aptly named sanctions levied by the NCAA killed the program, shutting it down for the 1987 season after investigators found that SMU had created a slush fund to pay athletes and prospects. But you probably already knew that.

Talking to McIlhenny makes one realize that even a truthful telling of events can sometimes paint the wrong picture. And that’s largely what has happened at SMU.

Since those sanctions were levied, the label of “cheater” has fallen upon anyone with relation to the Mustangs’ program during that time.

The legacy of the personnel and players that weren’t making or receiving payments during the ’80s has been glazed over, including McIlhenny’s. In the wake of the “Death Penalty,” their stories were the true casualties.

The 10th and 11th tree

McIlhenny would know his tailgating spot even if the number spray-painted on the curb somehow disappeared overnight.

“Between the 10th and 11th tree on the right as you’re walking up the Boulevard.”

It’s the spot he and his family have owned since Boulevarding began in 2000, when SMU’s Gerald J. Ford Stadium opened.

McIlhenny’s family – father, mother, sister and brother – all attended SMU. They still depend on Lance to lug the tailgating equipment back-and-forth. After all, he lives only two blocks north of campus.

“We grill bratwurst and hot dogs,” McIlhenny said as he patiently sipped coffee at a café near campus. “I do the grilling until I can coax someone else to take the tweezers.”

Another breezy autumn Saturday means the Mustangs are hosting East Carolina, Central Florida, Connecticut, or some other football non-power that his father Don wouldn’t have faced when he played for SMU in the ’50s.

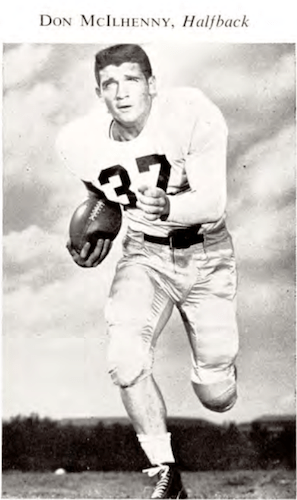

Don went on to play in the NFL, though he was mostly used as a backup halfback. Scoring the first rushing touchdown in the history of the Dallas Cowboys franchise is his one claim to fame.

Lance never played professionally, but put together quite a resume while on The Hilltop. He graduated as the winningest quarterback in school history with a record of 34-5-1.

“I never felt like I was anything special,” McIlhenny said. “I was just part of a team that won a bunch of games.”

“A bunch of games” is an understatement – a humble, modest deflection from a college football legend turned real estate titan.

McIlhenny’s tailgate is popular with friends, and not just because he keeps a surplus of beer on hand.

Friends stop by to reminisce about the days when he ran the “Pony Express” – when McIlhenny, Eric Dickerson and Craig James made the Mustangs seem untouchable.

That team down in Austin

“If we lose that game, I’m probably fired.”

Former SMU head coach Ron Meyer chuckled those words through the phone shortly after returning from a bass fishing trip.

Meyer, who was hired in 1976 and tasked with turning SMU’s football program around, hadn’t produced a winning season in four tries. Things were supposed to be different in 1980.

The game Meyer was referring to was the Mustangs’ midseason matchup with the No. 2 Texas Longhorns, whom SMU hadn’t defeated in 14 years.

“We were loaded,” McIlhenny said.

To match a talented defense featuring multiple fifth-year seniors, Meyer had brought in countless offensive weapons, including highly recruited running backs Dickerson and James to trade-off snaps in the backfield. Senior Mike Ford, who already placed top 10 in all-time NCAA passing yardage, was to start at quarterback for the entire season.

Meyer had gathered a plethora of talent. And that was the problem.

On offense, the Mustangs lacked an identity. SMU’s pass-first tendencies from previous years no longer worked with Dickerson and James waiting to run.

Steve Endicott, SMU’s offensive coordinator, would later move on with Meyer to coach in the NFL with New England and the XFL with Chicago. After SMU fell to Baylor and Houston in back-to-back games it shouldn’t have lost, Endicott knew a change was needed.

“I tried to incorporate too much in the offense,” Endicott said. “We weren’t really good at anything.”

The incumbent Ford, who had returned from a broken leg he sustained the season before, played terribly in both losses. He fumbled a snap on fourth down against Baylor, resulting in the 32-28 loss.

“Our offense was just sputtering,” Meyer said. “We couldn’t really get a handle on whether we were a running team or a throwing team.”

Meyer felt the season and his job slipping away with the Longhorns next on the schedule. He benched Ford and opened up the starting job. By practice on Wednesday, Meyer had found his man.

“Ron came in my office and said, ‘Hey, we need to ditch Ford and go with the freshman,’” Endicott said. “I was kind of surprised.”

“‘You’re the boss,’ I told him.”

Meyer wasn’t blowing smoke. He promptly informed 19-year-old McIlhenny that he would be starting in Austin, against the No. 2 team in the nation, in front of 73,000 people, on ABC’s national broadcast, with two days notice.

The average freshman would have wilted at the idea. Luckily for Meyer, McIlhenny wasn’t average. Meyer said McIlhenny didn’t shy away from the news whatsoever. After beating out SMU’s other five quarterbacks for the job, McIlhenny called his family and told them to be in Austin on Saturday.

“It was an awesome week,” McIlhenny said.

Everyone was hesitant at the move. McIlhenny hadn’t played a snap of college ball. He wasn’t incredibly athletic. He could throw, but wasn’t known for his arm. His small 5-10 frame didn’t instill much confidence either. He was quick, but not fast.

“I think Lance was the only one that really had the extreme confidence and belief in himself that he could really get it done,” Meyer said. “Once we committed to the running game, Lance fit it to a T.”

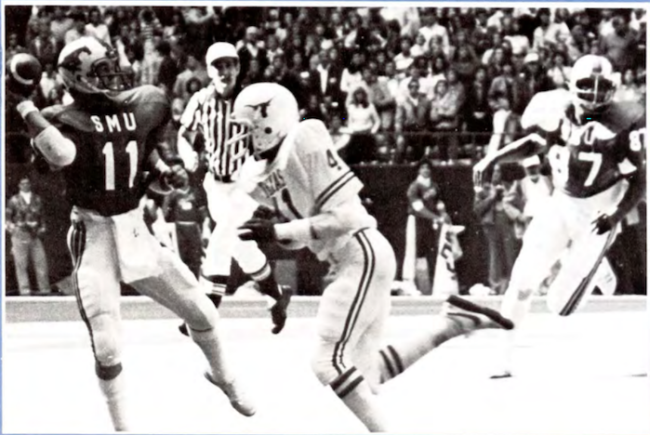

The Mustangs came out in an I formation and kept pounding the ball. The Longhorns’ defense, which had prepared for a completely different style of attack, was blindsided.

McIlhenny led SMU down the field, completing only one pass in the entire game for a measly three yards.

“People were making their blocks,” McIlhenny said. “Kicking the ball out to Eric and Craig… we won 20-6 that day.

Thus, the “Pony Express” was born.

“It really was our coming out party,” Craig James said, whose 53-yard run gave the Mustangs the lead that day.

McIlhenny would not only become the most successful quarterback to play at SMU, but also in the history of the Southwest Conference. During McIlhenny’s time at SMU from 1980-1983, he led the Mustangs to two conference championships, two bowl games and four consecutive 10-win seasons. In his junior year, SMU went 11-0-1 and was ranked as high as No. 2 in the nation by the Associated Press.

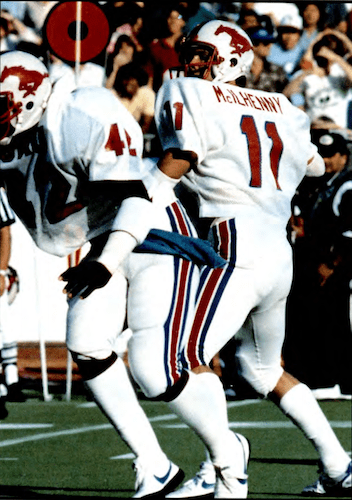

Meyer’s gamble on a 19-year-old paid off. McIlhenny would become the greatest option quarterback in the history of college football.

An obvious decision

While Meyer didn’t know if the young McIlhenny would be able to perform that Saturday in Austin, he was fully aware of what the SMU legacy could do with a football.

With McIlhenny playing high school ball just up the road at Highland Park, both Meyer and Endicott had a front row seat to watch him learn the option. McIlhenny’s opportunity with the Scots came much like his break at SMU. The senior quarterback got hurt, and head coach Frank Beavers taught McIlhenny the “Houston Veer” — an option style attack with many similarities to what the Mustangs ran years later.

“If your tackle and tight ends make their block, then it’s me against the defensive end,” McIlhenny said. “If he takes me, then I can kick it out.”

“He had the guts of a high diver,” Meyer said. “He’d go right up to the defensive end and either keep the ball or flip it at the last moment. He had a great sense of timing. Most option quarterbacks come down and pitch it way too soon. It allows the defense to react quickly and negate the play. Lance would come right down, jump into the defender’s lap, and then pitch it.”

“He was a magician on the option,” Endicott said.

“He could pitch it over people, under people, around people. I didn’t talk one second of technique with him. I didn’t tell him one thing. He had it all. He taught me more.”

McIlhenny’s skill with the option attracted many suitors. SMU, Arkansas, Texas A&M, Oklahoma, Alabama and Nebraska all wanted him. And yes, the Mustangs were once considered in that company.

But Meyer had an “in.” In fact, he had multiple. SMU had recruited and signed McIlhenny’s brother the year before.

Being the hometown school his father played at, SMU was the one. Lance had already been attending SMU football games since his family moved over from Preston Hollow when he was in the first grade. Back then, SMU games were packed with enthusiastic fans, unlike today, when the head coach has to hand out ice cream and ask for students to come.

“I guess my decision was pretty easy,” McIlhenny said. “There’s coaches that are coaches on the field, and then there are coaches who are salesmen. [Meyer] was a great salesman.”

“I’d be shocked if [McIlhenny] didn’t [commit to SMU],” Endicott said. “He was blue and red through and through.”

McIlhenny claims he never received any cash incentives to commit to SMU – maybe because those writing the checks never thought he would play, or maybe because Meyer knew he had the kid locked up. After all, the general perception is that SMU was giving money to every player. McIlhenny said the higher-ups were much more selective.

“It wasn’t everyone on the team,” McIlhenny said. “It was a select group. By the time we were seniors, we were making our way out of that.”

McIlhenny only received one gift – a small cash amount he found in his locker one day after practice, and only after he had won the starting job. He received the cash, coincidentally, just days after he saw a team staffer taking money out of a laundry bag.

McIlhenny never received Meyer’s alleged “hundred-dollar handshake.” He was never gifted a Datsun 280ZX, the preferred car of the Mustangs. Again, McIlhenny never felt he was “anything special.”

“It’s just TCU”

McIlhenny was already working in real estate for former Dallas mayor Bobby Folsom when the NCAA crushed SMU football.

He had no aspirations of playing professionally and didn’t have the size or skillset to do so.

Dickerson and James, of course, went on to great professional careers.

When people think of the Pony Express, those two come to mind, not the guy who was pitching them the ball.

The pair undoubtedly overshadowed McIlhenny’s contributions, but he doesn’t mind that.

He was more than happy to raise a family in Dallas.

But sticking around meant McIlhenny would have to witness what SMU was to become – a barren wasteland of bad football.

“The Death Penalty really, really hurt this school,” McIlhenny said.

“The repercussions of it all, the stigma, the association, you can’t ever change it.”

Schools like TCU and Baylor used to be SMU’s annual punching bag, but as conferences expanded, the now irrelevant Mustangs became the last dog at the bowl.

The others grew up, and SMU shriveled like a runt.

“Everybody puts Baylor up here and TCU up here,” McIlhenny said. “It’s just TCU. They’re beatable. Let’s go kick their a**.”

If history is written by the victors, or in McIlhenny’s case, the one with the most victories, someone must have forgotten to hand McIlhenny the pen.

Ultimately, the NCAA wrote SMU from the histories.

But back on the Boulevard, it’s gameday, and McIlhenny is still smiling, not caring too much about his legacy.

In many ways, he still resembles the boy his coaches loved coaching – the boy who grew up to love Dallas and SMU more than anywhere else in the world.

“There were three guys in my coaching career that I couldn’t wait to see everyday, and Lance was No. 1,” Endicott said.

“He was the best competitor I ever coached.”

Reece Kelley Graham is a staff writer for The Hilltopics, a Rivals.com site. Follow him on Twitter at @ReeceKelleyG.