The events of 1968 are not only historic, but arguably affected the trajectory of the country’s political leadership and hushed the voices of social justice, creating a product of silent voices, even in decades to follow. The assassinations were clearly an attempt to silence voices, and Dr. Martin Luther King and Robert F. Kennedy were certainly silenced, but the messages were carried on by others.

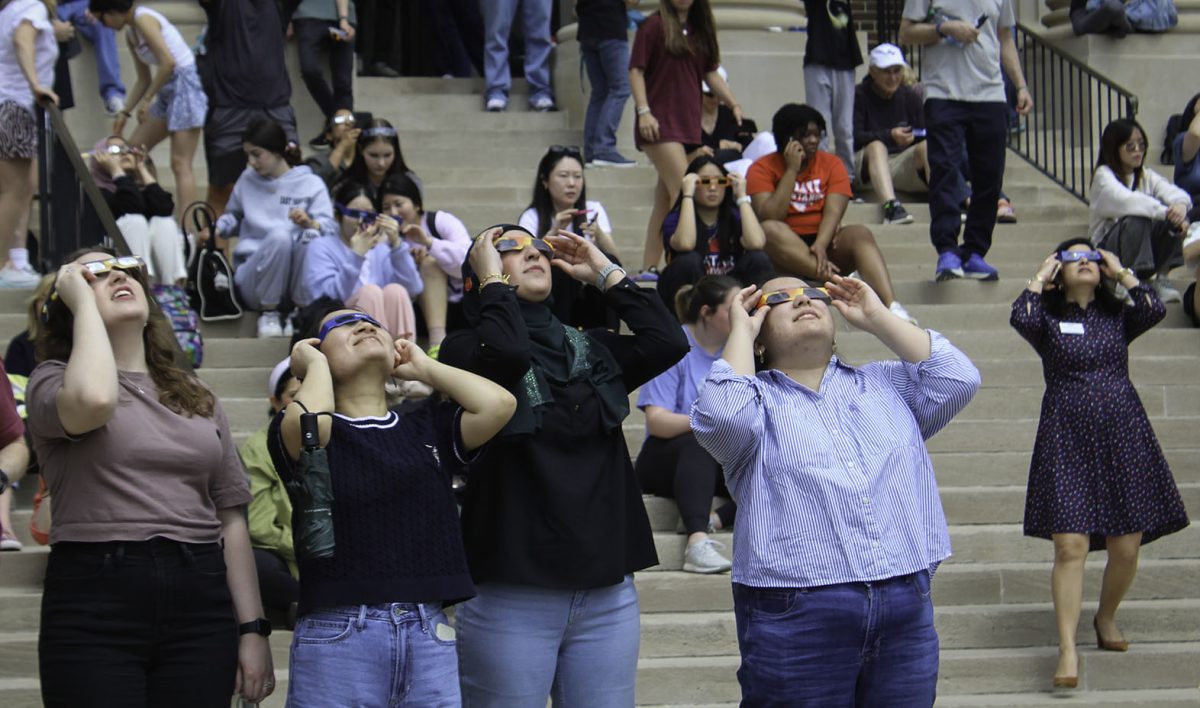

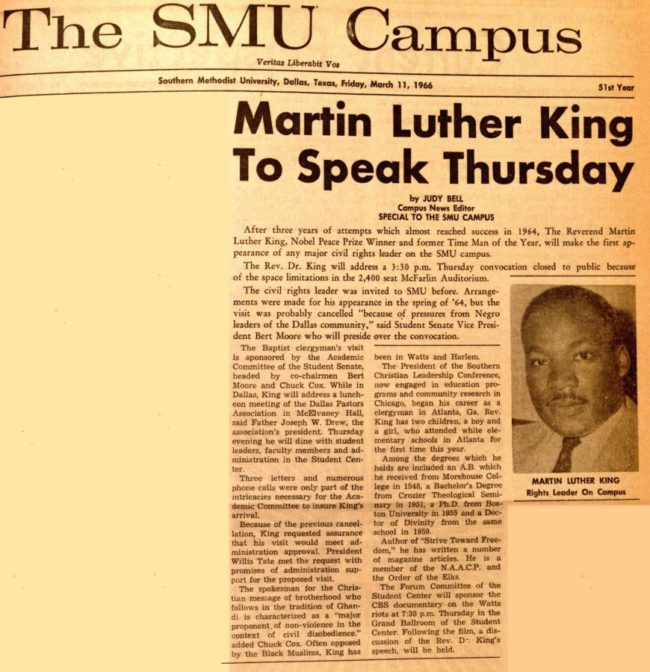

In August of 1965, Dr. King was invited by Bert Moore, the vice president of the SMU Student Senate at the time, to participate as a speaker in the annual guest lecture series. On the afternoon of March 17, 1966, Dr. King spoke in McFarlin Auditorium to a packed, then not fully integrated crowd, accompanied by an abundant police presence.

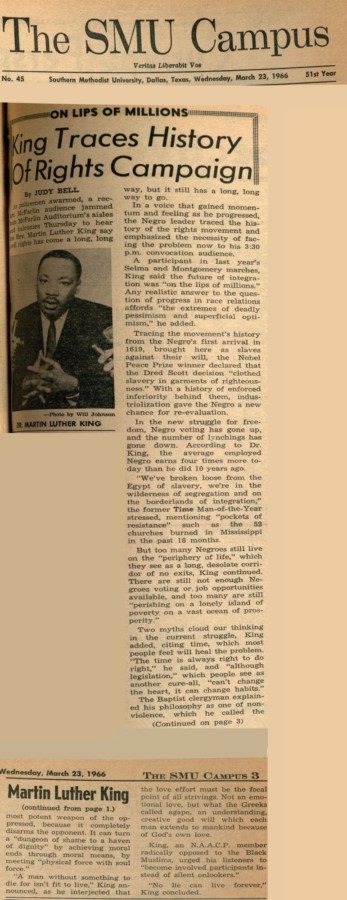

With utmost eloquence, Dr. King’s speech projected the unjust truths of the black narrative amid America’s hostile race relations. He reiterated the length of the strides to come, without detracting from the progress made, in effort to instill hope. King said:

“Now it is a fact that we have come a long, long way, but it isn’t the whole truth. And in order to tell the truth, I must give the other side, and if I stop at this point, I may leave you the victims of a dangerous optimism. I may leave you the victims of an illusion wrapped in superficiality. So, in order to tell the truth, it is necessary to move on and say not only have we come a long, long way, we still have a long, long way to go before the problem of racial injustice is solved in our country.” – MLK, Jr.

According to The Dallas Morning News, Moore, who died in 2015, described this day as the highlight of his life.

Moore orchestrated the entire event, from sending the invitation, to picking Dr. King up at the Dallas Love Field terminal. In an interview in 2015, with staff writer Melissa Repko of The Dallas Morning News, Moore talked about his fears about how the SMU community would react to Dr. King’s presence on campus.

“Racism was pervasive and taken for granted,” Moore said. “There was no sense that this was wrong. It was, “This is always the way we’ve done things.” – Bert Moore

Despite Moore’s worries, Jerry LeVias, SMU’s first black athlete, Bill Clements, who would become the governor of Texas, and Charles Cox, the Students’ Association Academic Committee Chair at the time, all reacted positively in their reviews of Dr. King’s speech.

LeVias was afforded a one-on-one meeting with Dr. King in which he gave LeVias advice about keeping his emotions in check juxtaposed with desire to react to the students and teammates on campus who attacked him, spat on him, and refused to sit next to him.

“It was sort of like being mentored by one of the greatest men who ever lived,” LeVias said.

Clements was in tears by the time Dr. King finished with his remarks, and Cox was just mesmerized by his voice.

“I remember being so incredibly impressed with his speaking abilities,” Cox said. “He spoke for about 60 minutes, and he didn’t have a single note.”

Despite the “us vs. them” narrative that seemed dominant in Dallas and the South at the time, Dr. King commanded the attention and presence of everyone in the auditorium. His Baptist values intertwined with his philosophy of non-violence proved to be a memorable and historic moment for both SMU and Dallas. King continued:

“And so the plea facing us today is to move on that additional distance that we have to go with understanding, with a concern for brotherhood, with the removal of all prejudices, with an understanding that all of God’s children are significant.” – MLK, Jr.

When reflecting on the year 1968, the same four topics emerge. They are the Vietnam War, specifically the Tet Offensive, the assassinations of both Dr. King and Robert F. Kennedy, and the student revolution that was concentrated in the U.S., but in fact involved a liberating and active uprising on a global scale.

In 1968, Dr. Rick Halperin, director of the SMU Embrey Human Rights program, was a first-year student at George Washington University in D.C., situated three blocks west of the White House. In his recollection of the assassination of Dr. King in Memphis, TN in April of 1968, Halperin reflected on his experience on Capitol Hill:

“I went up to the roof of my dorm and I could see everything as D.C. erupted in riots and violence. All you could see, as darkness fell into night, was trash, fires, ambulances, police cars, and hundreds of people who took to the streets shooting at planes that flew right above the city. All you could hear were sirens and gun shots. It was just outrageous.” – Dr. Rick Halperin

Two months later, in June of 1968, Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated in the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles after winning the California primary. Halperin continued:

“It seemed like the country was coming apart at the seams. It’s hard to describe the daily violence that the country was enduring. After the two assassinations of King and Kennedy, America has never found a national moral voice of sanity since.” – Dr. Rick Halperin

For Dr. W. Marvin Dulaney, associate professor emeritus of history at the University of Texas at Arlington, the assassination of Dr. King in 1968 was the end of the civil rights movement as well as King’s “larger-than-life role and influence” on the movement itself. Not only did the nation lose a social justice leader and voice, but Dulaney goes further to denote the culmination of his political and social tactics:

“Indeed, the assassination of Dr. King made it very clear to my generation that “loving your enemies,” “turning the other cheek” and adopting nonviolence as tactics would get us killed. While we loved and honored Dr. King, we saw that the resistance to his very mild and legitimate demands for the nation to honor its own creed of equality of opportunity, voting rights and basic human rights were demands that the nation could not fulfill.” – Dr. W. Marvin Dulaney

The map below indicates the locations of the deaths of Sen. Robert Kennedy, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., the location of the auditorium where Dr. King spoke to the SMU community, and George Washington University where Dr. Rick Halperin was a freshman when the assassinations occurred.

Thnks 2 @SMUAlum @RevDrMikeWaters Charles Cox @SMUsenate 4 presenting transcript of Dr. King's speech @SMU in 1966 pic.twitter.com/ljsDUtClxs

— SMUCommunity (@CommunitySMU) January 15, 2016