By Sara Ellington

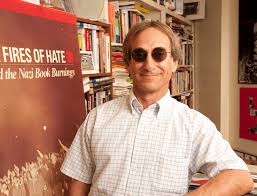

In his signature circular tinted glasses, nice cargo pants, and button-up polo that always has a pen and marker in the pocket, Dr. Rick Halperin is the endearing face of the SMU Human Rights Program. He speaks with a Southern accent from growing up in Alabama and takes his time with his words—as someone who studies the worst of human history, he knows the power of them.

In 1968—widely considered one of the most tumultuous years in history—Halperin, then a sophomore in college at George Washington University, went to Europe for the first time to study abroad in Paris. With eyes as big as plates after visiting Holocaust sites, he soon came across Amnesty International and realized he could actually make a career out of human rights.

Two decades later that dream began materializing. In the spring of 1989, then only his fourth year at SMU, Halperin proposed adding a human rights course to the history department and was also elected to the board of Amnesty International USA that summer.

After six years of teaching “America’s Dilemma: The Struggle for Human Rights” and 13 years of traveling alone to Poland’s Holocaust remembrance sites—on top of the travel he did with Amnesty—Halperin was able to merge the two experiences and the first group trips to Poland began in 1996.

Anyone who has traveled with the program can talk about its transformative impact, but few can speak to the degree of that change as Lauren Embrey. In 2005, Embrey was a Masters of Liberal Arts student and went on the trip after hearing about it in one of Halperin’s classes. Within six weeks of returning home, Embrey and her sister Gayle set up a meeting with Halperin to ask if their family could make a $1 million donation to the university specifically to create a human rights program, and if he would consider being the director.

Halperin didn’t even need time to consider, excitedly accepting with a grin and “You’re darn right!” For him, he waited his whole life for this kind of opportunity; for Embrey, she wanted to give young people the opportunity to help move the world in a more peaceful, equitable, loving direction through her family’s foundation.

In 2007, the program officially began as a minor—much to Halperin’s protestations, who knew enough students would be attracted to a major from the outset. Indeed, the first person graduated with a minor the following year, and from 2007 to 2011, Human Rights was the fastest growing program on the entire campus. With the university pleasantly surprised (and Halperin pleasantly vindicated), the December 2011 board of trustees meeting established the major, and the first two students to graduate with a B.A. in Human Rights stayed an additional semester in order meet any outstanding requirements. Upon degree conferral in Spring 2019, the program will have graduated over 100 majors.

Meanwhile in 2012, Dr. Brad Klein just graduated with his PhD in Religious and Theological Studies from the University of Denver and was looking for his next step. When a former classmate living in Dallas told him about an opening in the human rights program, it seemed like exactly what he was looking for: by covering all the facets of human rights, there would be no need for compromising values.

Paralleling Halperin’s sense of excitement when Embrey proposed directing the program, when Klein was given the chance for final questions in his one-on-one interview with Halperin, he asked “what else can I say to make sure you see I’m the right candidate?”

Whatever he said, it worked. Klein joined the small team in the fall of 2013 as assistant director, and hit the ground running with establishing the program’s five-year-plan. According to that document, SMU ultimately wanted to be “at the forefront of a growing movement to see human rights represented across the higher educational landscape” through expansion in graduate education opportunities, local community outreach, global connections and name recognition.

For the most part, Klein thinks the initiatives have been successful. But as with any plan, goals have to be re-prioritized and changes in context demand a change in strategy. Primarily, the hopes for masters and PhD level graduate programs have been put on hold due to financial insecurity—an unexpected frustration at a university as wealthy as SMU.

To achieve that milestone and others, the program has taken money matters into its own hands. On December 10, 2018—Human Rights Day—the program launched its Dignity Endowment Campaign. By marketing its unique qualities through student, faculty and community member video testimonies, the campaign hopes to reach a goal of $10 million. On top of housing the largest undergraduate program out of the six other universities in the country—none of which are also in the South—the funds would make SMU home to the first endowed undergraduate degree-granting human rights institution. With those resources, it may finally be recognized as the country’s epicenter of human rights education, as Halperin firmly believes it is.

Another major frustration is unfortunately all too natural given SMU’s demographic makeup as a PWI (Predominantly White Institution). The human rights program’s all-white staff is led by two men while most students in the program are women of color. (For reference, as of 2017 SMU’s faculty is 39.4% female and 18.5% minority.)

This issue, too, returns to the importance of the endowment campaign and the potential it brings. Without the resources to hire and compensate its own faculty and staff, the program misses out on the perspectives and experiences a more diverse office would bring. But Community Outreach Coordinator Hope Anderson ’17 points out both Halperin and Klein have had their own reckonings with privilege as straight white men, and that’s led them to a place of clarity regarding how to facilitate the most impact, like focusing on recruiting diverse students.

Both 2018-2019 post-baccalaureate fellows—Kendell Miller-Roberts and Jessica Pires-Jancose—are women of color, and they hope their presence over the past year has helped students see themselves represented more. “Because the program is majority black and brown women, that imposter syndrome is so much stronger,” Jancose says. “Half the battle is actually doing the work, and half the battle is beating down that feeling of ‘I don’t belong here.’” Which is why, she continues, such a focus of the program is cultivating the inner empowerment of each student and helping them mobilize their activism.

Anderson is proud to agree the staff’s main role is to hone and tweak student initiatives. “The program is not a staff-powered program. The only lifeblood we’ve got is our students.”

In one way or another, every single person in the office echoes that sentiment: not only are the program’s students the best ambassadors for it to continue gaining support from the university and community, but they are the force behind all the success in the first place.

“Despite areas of improvement and despite bureaucracy, we still come here every day because we love the students and we think this work is worth doing,” Miller-Roberts concludes.

Though Anderson believes in it’s in the nature of human rights students to give back, curating a safe, encouraging space for that inclination to prosper takes daily intentionality. For one, Program Coordinator and all-around office mom Sherry Aikman stocks the entrance area with treats to make the space inviting (just in case the near constant free real food leftover from events wasn’t enough for college students).

The staff even limits their reservation of the conference room to a couple hours once a week in order to leave as much as space as possible for students to build connections. Walk in to Clements 109 at any time of day and that’s what you’ll see, too: whether it’s students laughing through event planning and study breaks, or privately having an emotional heart-to-heart with one of the staff (the only time office doors are closed).

Klein has a master’s degree in Pastoral Care and Counseling and strives to provide a moment’s rest and encouragement for students who need it because the blood, sweat and tears is very real in this line of work. For the program to live up to its motto of demanding dignity, there’s a need to strike a balance between issues-based work and what Anderson calls “you-based work.”

Though this culture would be undoubtedly beneficial across academic disciplines, it is uniquely tailored for human rights students, who expectedly study the worst of humanity, but just as often the best of it. Through her time both as a student and now two years on staff, Anderson has found that in this community, “joy and sorrow are so deeply interwoven.”

It’s fair to say her and Klein speak for the rest of the program when they say the point of this program is to foster resiliency when the sorrow and pain get too heavy. Inside and outside of the classroom, Klein engenders a sense of longevity, of doing work that is just as perpetual as the systems it’s aimed to reform, and in a sustainable way.

No matter the result of the campaign or future of the program, Anderson believes instilling that framework is enough to bear the march toward justice. Of course—ever the optimists—SMU human rights still firmly its best days are yet to come.