For the first time, the Perot Museum of Nature and Science has collaborated with the University of Witwatersrand in Africa to welcome two new ancient human relatives to Dallas.

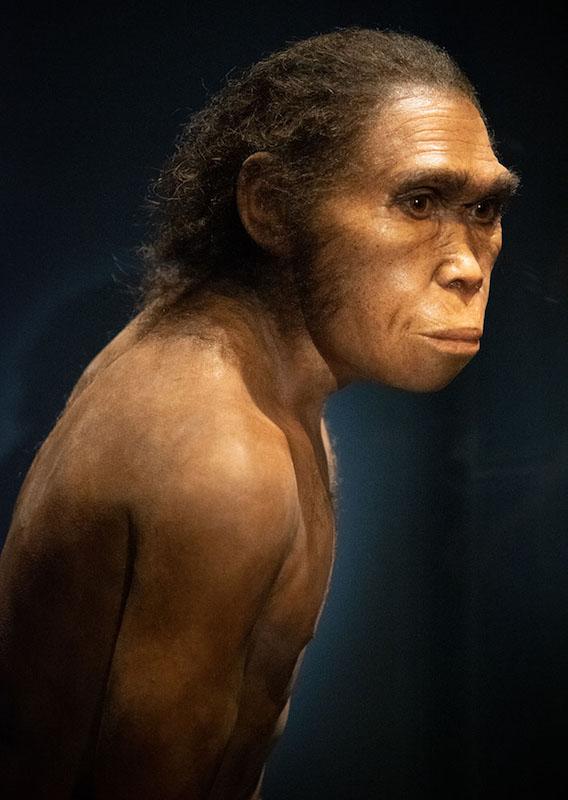

In their new bilingual (English and Spanish) exhibit, “Origins: Fossils from the Cradle of Humankind”, Australopithecus sediba, and Homo naledi will be on display for the public now through March 22, 2020.

The exhibit showcases the story of a young boy who stumbled upon the remains of Australopithecus sediba and the mission that six female “underground astronauts” took to get to the bones of Homo naledi.

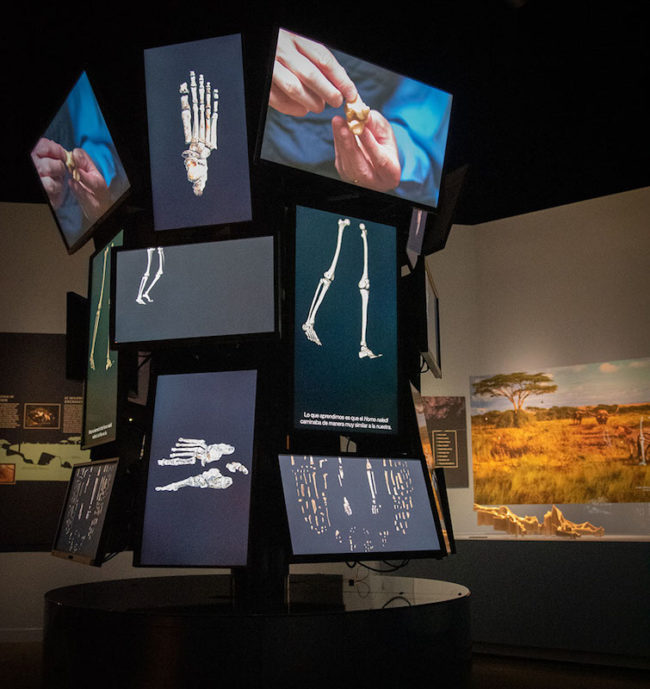

Within the exhibit, guests can watch scientists study the fossils in real-time. Visitors can also participate in an interactive challenge that involves squeezing through an 18-centimeter gap that resembles the underground location of the Homo naledi bones.

People of all ages are welcome to try using technology to discover their own fossils amongst a field of small rocks.

When it comes to discovering fossils, Becca Peixotto, a member of the Homo naledi excavation team and the Director and Research Scientist of the Center for the Exploration of the Human Journey, is no stranger to it.

“It’s exciting,” Peixotto said. “It’s a part of our shared human history, and I’m one of the first people to see it.”

For Peixotto, the fossils she helped excavate mean much more to her than another piece of scientific data.

Although stressful and “way scarier than going underground,” Peixotto said that bringing the fossils all the way across the Atlantic Ocean was meant to highlight new research and “give people in Dallas a unique opportunity.”

Since the Perot Museum has the Center for the Exploration of the Human Journey, which focuses on paleoanthropology and archaeology, it just made sense to Peixotto to bring the exhibition here.

More importantly, Dallas has “an audience that might not ordinarily get to see this kind of thing or engage with this kind of material,” Peixotto said.

Ultimately, the arrival of these fossils in Dallas provides the public with an opportunity to talk about evolution. Drew Montgomery, Science Communication and Outreach Fellow, said this “can be a little bit of a touchy subject, especially in the south, especially in Texas, and it doesn’t necessarily have to be.”

To change the conversation, the exhibit is working with schools, local libraries, and they are educating teachers on how to teach evolution.

As researchers work to educate the public, they also acknowledge the hypocrisy and narrow narrative within the Paleoanthropology community. Peixotto said that, traditionally, Paleoanthropology is a very closed field and very much an “old boys network.”

“We lose a lot of really good science and scientists when our fields operate that way,” Peixotto said.

By adopting the Open Access Research idea, created by Lee Berger, lead investigator of both discoveries, more people of diverse backgrounds will be included in scientific teams and the research process will become more transparent in the future.

“You don’t have to be a paleoanthropologist or an archaeologist… anyone should be able to learn about these things,” Montgomery said.

Overall, the discoveries of Australopithecus sediba, and Homo naledi have led the field as a whole to “understand that there is more out there to be discovered,” Peixotto said.

In the grand scheme of things, so little is known about how humans evolved into one species and even less is known about what the future may look like. However, with an open conversation, looking at our “Origins” is the first step towards answers.