God not necessary for love

Ever since I was young, I was taught that love is one of the gifts of the Holy Spirit, freely given by God to man in spite of his flawed nature. So if as many other people buy this interpretation as my religious teachers might suggest, I have an uphill battle when it comes to defending love without God.

Perhaps critics of my position are correct. Perhaps there really is no reason to give of oneself freely to those close to us if there is no perfect exogenous model whence this love derives. Perhaps Ayn Rand was right: altruism is a dangerous corruption of human morality and the only good life is one perpetually mediated by rational self-interest. Perhaps there is no purpose to human existence besides the continued propagation of our species, and any people who get in the way of this goal are perfectly expendable; no use dwelling on those who suffer because “that’s just the way the cookie crumbles, man.”

And yet, I find these hypotheses as painful to suggest as they must be for any reasonable person to read. I reject the notion that a godless society is one in which humans necessarily lack regard for one another. In fact, even with God, human beings don’t do a particularly good job of loving one another. When two depraved young boys see it fit to kill and maim hundreds of people in the name of their God, or when self-proclaimed Catholics like New York State Senator Greg Ball can go on TV arguing that one of those perpetrators ought to be executed (something the Catholic Church strictly forbids), I wonder what kind of cognitive dissonance must be clouding their views to make them ignore explicit Scriptural commands.

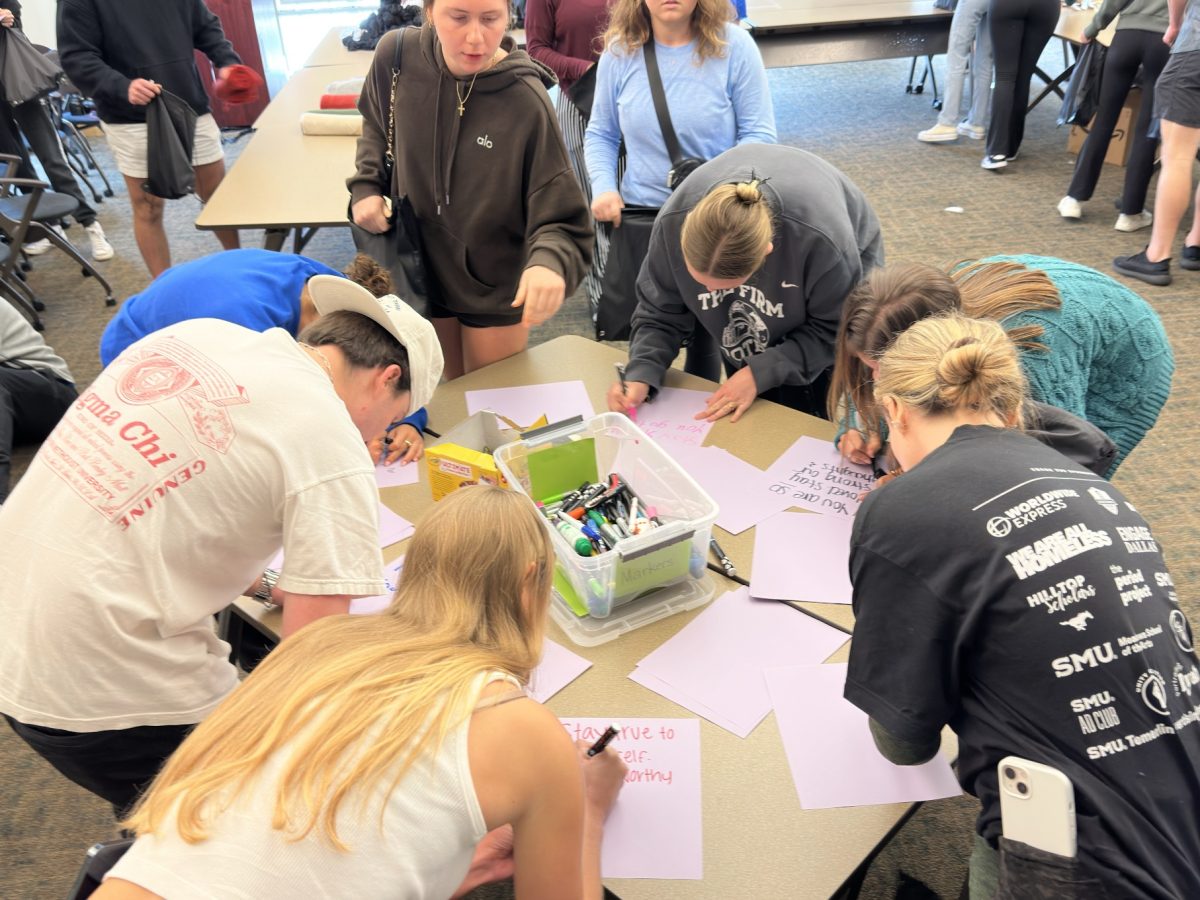

But the fact that human beings do fall short of this imperative to love, regardless of whether that command emanates from God or from within an inborn conception of human decency, does not mean that it should be totally disregarded. And in spite of the unimaginable and unconscionable atrocities human beings have committed throughout history, I remain confident that the human potential for love is strong. When runners participating in the Boston Marathon cross the finish line and run three more miles to the hospital to donate blood to bombing victims; when the city of West, Texas asks that people stop donating certain relief goods because they simply don’t have the resources to maintain people’s generous contributions; when a good friend can cheer an ailing buddy up just by staying close and hardly saying a word; when a couple of people married for over 50 years can share a look with one another as if they had just started dating again — that’s how I know that there is love. I might not be able to quantify human compassion or explain it fully through evolutionary or biological processes, but I know that it is most certainly there, and it is something worth living for, regardless of whether or not God compelled us to do so.

Rather than continue rambling, however, I thought I should co-opt the words of a humanist author who expressed this sentiment far better than I will ever be able to: as Kurt Vonnegut wrote in his grossly underrated “The Sirens of Titan,” “A purpose of life, no matter who is controlling it, is to love whoever is around to be loved.”

Bub is a junior majoring in English, political science and history.

Religion important in love

Whether we hear about it from Romantic poets, cognitive scientists, self-help gurus or religious folk, love is central to the human experience.

Everyone has some theory about love, whether it’s a fabrication, just chemicals in the brain or if there is in fact some metaphysical thing called love.

I think love involves both action and an orientation of the spirit.

Thus, it seems like love is consciously chosen. Love is displayed through acting in certain ways towards others, but also in sentiments, emotions and thoughts.

The English language is severely hindered in that it only has one word for love, with no chance of differentiating between erotic love, the love of friendship, Platonic love or something transcendent. But we might think that all of these types of love have something in common.

I think that, of these manifestations, the uniting factor is something that transcends all of them. In particular, I’m thinking of an eternal love that comes only from the Divine.

These types of love are all shadows of the Christian notion of love, which holds that God is the epitome of love.

Love is not this or that action or this or that emotion; love is from and of God and shows itself through actions.

In the words of the 19th century Danish philosopher and theologian, Soren Kierkegaard, “for one is not to work in order that love becomes known by its fruits but to work to make love capable of being recognized by its fruits.”

Love, then, is something wholly otherworldly, and cannot be reduced to simply this or that set of actions, but we can see God or love in particular instances, like flashes of lightning that intimate the transcendent idea of Light.

Kierkegaard’s words are even further instructive in that he calls us to understand love as a duty.

This duty, to love, is eternal and unwavering against any change of emotion or circumstance.

Here is where Kierkegaard’s understanding of Christian love runs up against our contemporary ideas of love. One does not fall in and out of love. Love is eternal, and our participation in loving is an instance of that love.

The idea that erotic fixation on someone is love undermines and degrades the notion of Christian love. One’s attachment to another person is hardly the epitome of love, and it may in fact be contrary to Christian love.

When we say, “I love you,” what we might mean is actually “I have some attachment to you, but it might disappear when you hurt or offend me.”

This is, by no stretch of the imagination, an inaccurate representation of love. Instead of abandoning the high idealism of Christian love to a secularized and naturalized view of love, we should strive to maintain the beauty and the duty that comes along with love as a manifestation of God’s divine nature.

Dearman is a junior majoring in political science and philosophy.