As college students, we commit to spending four years on campus studying for a degree. We commit to pay expensive tuition and give up nights and weekends studying. We commit to take classes and pass them. We commit to specializing in one or more fields so that we might know something at the end of our time here. We have fun, too, but in essence, serious students come to college with the primary motivation of actually learning something.

We agree to certain rules, knowing that if we do not pay attention or pass our classes that we will not be rewarded with a degree. Strangely, however, we never explicitly commit to the real pursuit of knowledge. Because there is no real penalty for refusing to expand our horizons, to push our minds to their limits, or to think about complex concepts outside of class. So where is our incentive to seek the learning that resides outside the pages of our textbooks and the walls of our classrooms?

The truth is that the system of modern education—classroom learning followed by homework practice—provides no clear method for discerning a student’s motivation, needs and retention of information. Although grades may reveal how well we played the game in the classroom and how well we synthesized the information at the end of the semester, they tell us little about what we actually know once the transcripts are mailed and the books are closed. The educational system, which in essence changes little from state to state and from Kindergarten to college, is broken. Because as long as we are tethered to our grade point averages, we will never truly be free to learn.

An appropriate alternative to the current, age-old model would be one that both allows measurement of student performance and yet encourages true learning. Unfortunately, such a perfect system exists only in our waking dreams. If the system cannot be trusted to ensure that we learn, then who can? The answer is both simple and necessarily complicated: we.

The truth is that because our current system is broken, the ethical responsibility of learning lies solely with the student. We are each responsible for ensuring we do our best to learn, despite grades. Yet this responsibility not for the faint of heart. Only the bold, wise few can make the choice to really learn.

Even fewer of us actually ever ask ourselves if we have really learned anything, or if it is knowledge or grades that is really more important. Why does our educational system not bring this challenge to us?

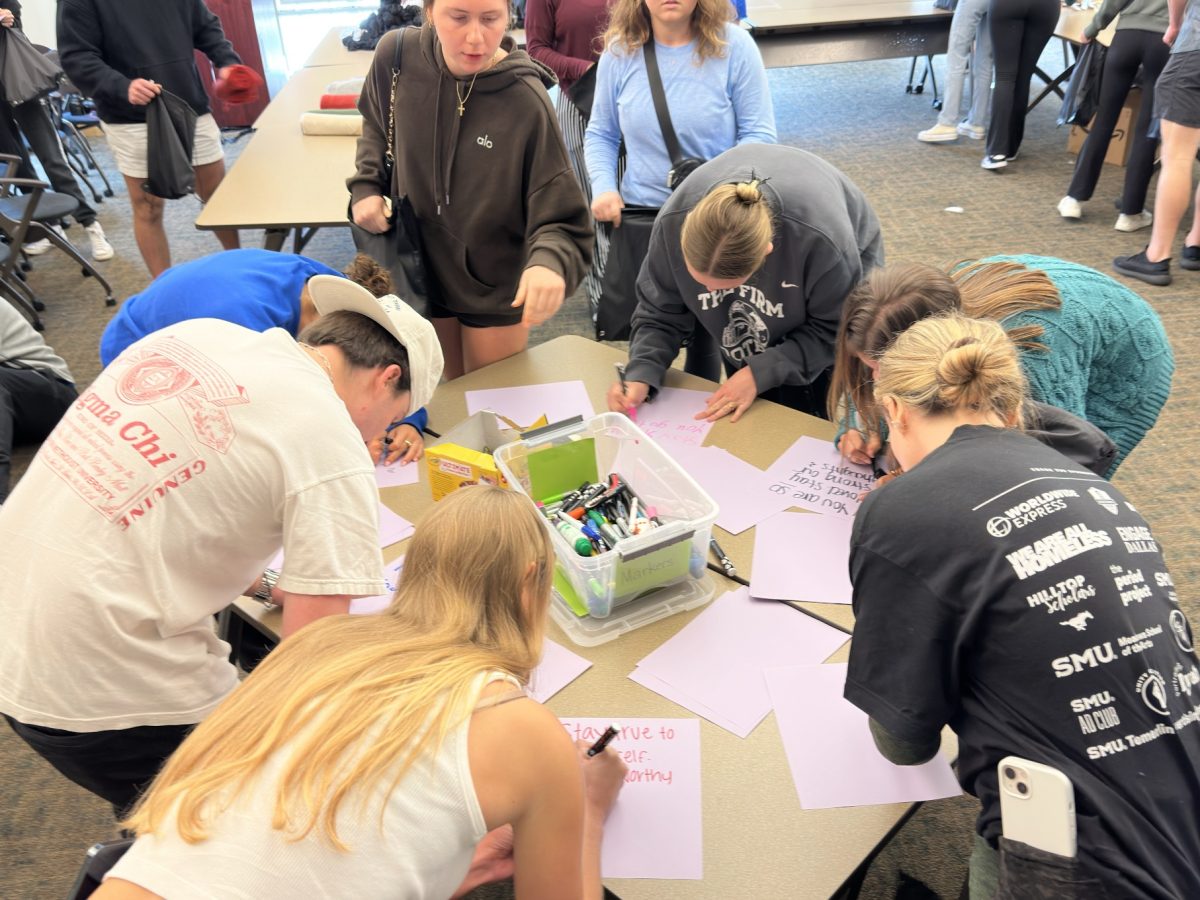

I believe that our university would benefit from presenting such a challenge to New Student curriculum. The ethos of Southern Methodist University as an academic institution could greatly improve if it would explicitly and unashamedly admit the flaws of the system that it represents. SMU should take the time to inform its students of the role they play in the development of their own intellectual formation and offer them a challenge. Just as new students pledge to drink responsibly, we must pledge to think responsibly. Such a formal pledge would be both innovative and responsible, helping SMU and its students to wisely seek the truth for which its motto stands: “Veritas Liberabit Vos”—the truth shall make us free.

Rebecca Quinn is a senior art history, Spanish and French triple major. She can be reached for comment at [email protected].