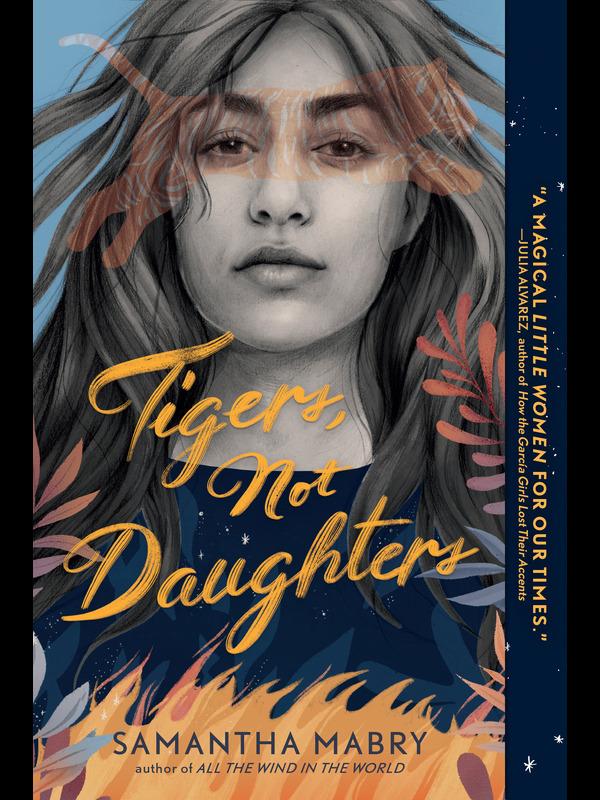

SMU Lecturer Samantha Mabry’s book, “Tigers, Not Daughters,” is an angry and unapologetic story about the many faces of grief. The novel offers a dynamic exploration of the nuances of sisterhood and trauma. It’s part ghost story, part family drama, and an unexpectedly appropriate read for the holiday season.

The title “Tigers, Not Daughters,” alludes to a phrase in “King Lear” that refers to Lear’s brutal and animalistic older daughters, Goneril and Regan. While Shakespeare’s angry daughters are villains in their story, Mabry reclaims “tigers” as heroines in her potent and complex characterizations of the daughters of the story.

The narrative rotates between the point-of-views of the Torres sisters as they cope with the death of their eldest sister, Ana. Burdened with an erratic and temperamental father, Jessica, Iridian, and Rosa Torres isolate their grief from one another and look for respective ways to absorb their older sister. The novel builds to a climax when Ana returns to the Torres home as a ghost, forcing the sisters to confront their dissolution head-on.

Mabry develops meaningful characterizations of each of the Torres sisters through their relationship with Ana, but where the novel truly succeeds is in its depiction of Jessica. Jessica, “the angry one,” copes with Ana’s death by trying to become her. “Something interesting happened four days after Ana died. Jessica was taking a shower… Jessica pulled a clump of her older sister’s hair from the trap. She knew it was Ana’s because it was longer than hers was, and because a few of the strands were gray at the root. Jessica held the wet strands between her fingers for a few moments before putting the hair in her mouth and swallowing it.” Moments like this strike a sensitive nerve and set Jessica’s narrative apart from the others.

The most poignant lines in the book come from Jessica’s grief: “Did he want to know, while Jessica was having sex with John in the back seat of her car the other night, she started crying so loudly and violently that she’d tricked him? John had thought they’d been cries of passion…but they’d had nothing to do with him.” Painfully colorful descriptions of Jessica’s coping habits are fueled by the intricacy of her character. She starts a relationship with Ana’s ex-boyfriend while stepping into a primary caretaker role as the girls’ father Rafe Torres collapses as a parent. “Rafe required nonstop words of love and loyalty. He also required food, so Jessica had to carve out money from her paycheck each month to keep the fridge stocked. She also had to make sure Iridian didn’t fossilize under the covers of her bed…” The attention given to Jessica’s simultaneous fury and love for her family reflects the novel at its sharpest.

Jessica’s voice is the strongest, but it is generally reflective of Mabry’s larger authorial voice, which is wrought with edge, dark humor, and a propensity to misbehave. “That’s the kind of man Rafe Torres was, the kind who would cling to a spatula in a time of crisis.” The notes of irony and ridiculousness within the prose resonate with the multidimensional reality of grief. There is a scene where Iridian and Jessica sit on the couch, watching television after a turbulent fight. Despite the charged energy and unresolved tension between the sisters, Jessica simply addresses the screen: “Seriously these actors are so ugly where do they find these people.”

Mabry evokes a candor that makes this novel about grief feel sincere and uncontrived. “In the weeks following their sister’s death, the Torres girls would play a game called Who Loved Ana Most. Iridian would always win because she was the best at remembering small details. For example: Ana’s left eye sat a little lower on her face than her right.” Although the book jacket may lure in readership with the promise of Ana’s ghost entering the narrative, it is Ana’s absence that pulls the reader in.

“Tigers, Not Daughters” doesn’t mince words or try to please. The story revels in the several absurdities and illusions of life, death, and the in-between. As the year ends and we draw into an often-melancholic season, it wouldn’t hurt to reflect on Mabry’s unpredictably comforting family drama.