At the legal age of adulthood, 18 years after birth, our government deems us responsible enough to vote for our country’s leader, purchase addictive substances and even die in service.

However, while we are apparently mature enough to do these things, we are considered unable to handle the effects of alcohol. As a result of our country’s lack of faith in America’s youth, a culture of taboo, binge-drinking and alcohol abuse has evolved. The solution to this problem lies in the elimination of a drinking age altogether. The decision as to what age is appropriate for a child to start consuming alcohol should lie in the hands of families and in their beliefs, because the system our government has adopted is obviously ineffective.

The apparent culture embraced by our society is that of boisterous drinking, often to excess. Portrayed in advertisements and emulated by our country’s youth, this practice of drinking in order to get drunk has enormous impacts on the lives of participants and those around them. What aspect of our culture perpetuates this need to drink to the point of delirium? The answer is directly related to the impractical age a person must reach to drink legally. The allure of such a forbidden substance causes children to perceive drinking as a glamorous adult activity, instigating the urge to drink, often irresponsibly.

One campaign utilized by federal agencies such as the Center for Substance Abuse Prevention and certain activist groups claims that drinking alcohol at an early age causes brain damage and can retard the growth of teenagers’ mental capacity. According to David J. Hanson, Professor Emeritus of Sociology at the State University of New York at Potsdam, this assumption is faulty. The medical research behind it is conducted on rats—which are given large doses of alcohol over a long period of time—or humans who are typically known alcohol abusers. Hanson said, “At lower levels of consumption, the ‘adolescent’ rats tend to be less susceptible to motor impairment and also less easily sedated than are older rats.”

The second piece of information inconsistent with this misused health statistic is evident around the world. Hanson calls cultures where drinking at an early age is not only legal, but culturally expected, “natural experiments.” He also attests: “In many societies most people drink and they begin doing so in the home from a very early age. Examples familiar to most people include Italians, Jews, Greeks, Portuguese, French, Germans and Spaniards.

There is neither evidence nor any reason to even suspect that members of these groups are brain impaired compared to those societies that do not permit young people to consume alcohol.”

How is it that our federal government advocates such an outlandish concept when there are physical contradictions to this theory around the world?

Part of what makes questions of alcohol so daunting is the amount of confusion associated with drinking laws. Texas has some of the worst, if not the most unclear, in the country. The Fort Worth Star-Telegram reports that, “In some counties, only four percent beer is legal. In others, beverages that are 14 percent or less alcohol are legal. In some ‘dry’ areas, you can get a mixed drink by paying to join a ‘private club,’ and in some ‘wet’ areas you still need a club membership to get liquor-by-the-drink.”

The temperance movements associated with these strict regulations seem to be harming the public rather than helping. According to Hanson, areas with harsh rules against alcohol consumption tend to have more alcohol-related problems such as drunk driving.

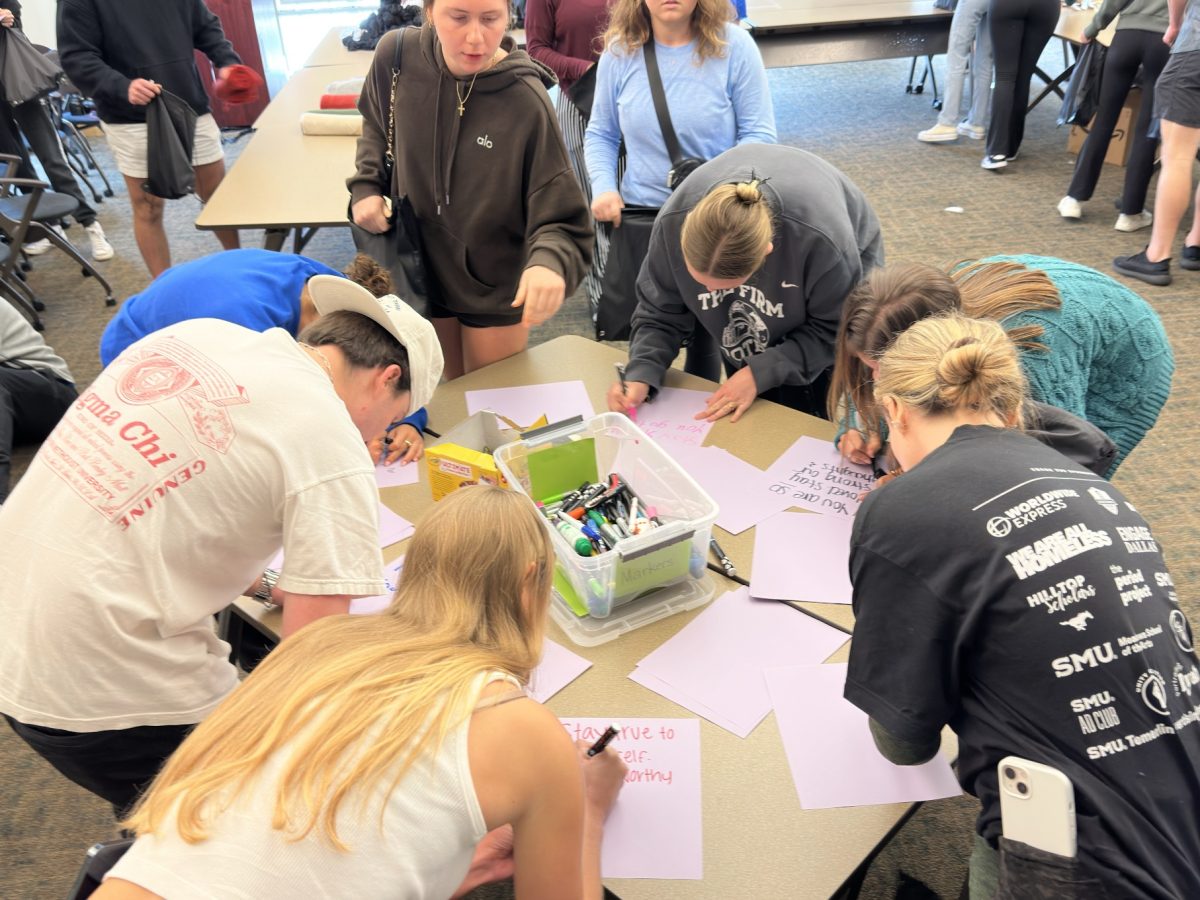

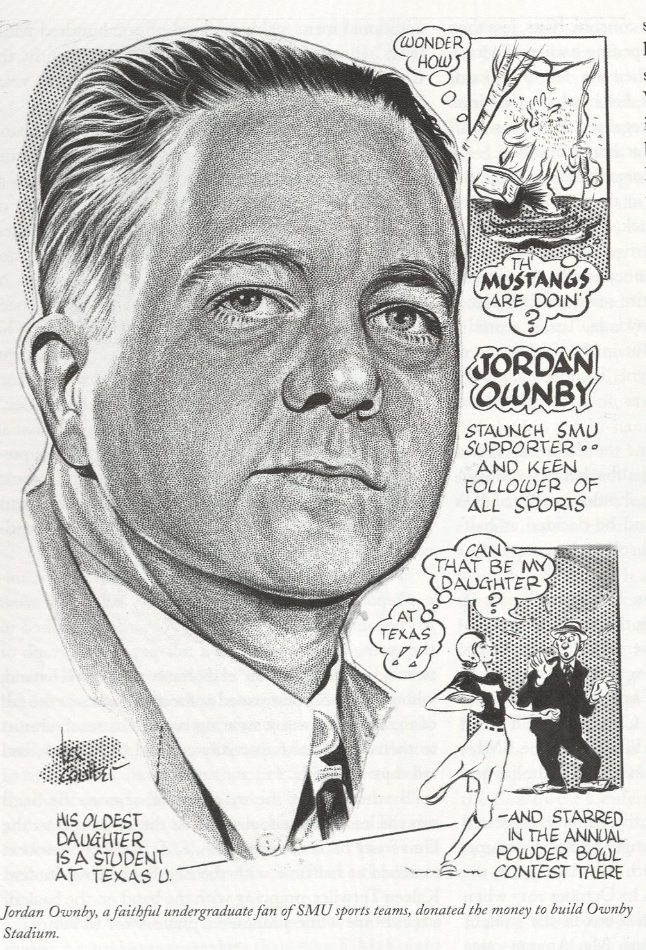

In addition to the issues circulating throughout the rest of the country, SMU’s endeavor to eliminate underage drinking on campus is hurting the student population more than it is helping. It would appear as though the administration’s plan to eliminate this “problem” is to target the school’s Greek organizations, notably the fraternities. Prior to the constant stream of fraternal suspensions and expulsions, parties hosted by these organizations were, in a sense, fairly responsible. The thought that eliminating fraternity parties would eliminate the issue of underage drinking is impractical if not naïve.

College students will continue to socialize and, like people around the world, will most likely use alcoholic substances. Focusing SMU’s resources on this issue will inevitably result in more alcohol violations, portraying students in a negative light within the university and elsewhere.

Last October, The Dallas Morning News commented on the drinking habits of SMU students: “Students say they’re well aware that three classmates died from alcohol or drug overdoses last school year. But, as SMU police logs and campus judicial records show, the partying continues.” Once again, rather than focus on why the number of violations has gone from 160 to 230 in the past year, the article continues to berate the number of minors caught intoxicated at a multitude of frat houses. The article also does not take into consideration the number of students unaffiliated with the Greek organizations drinking off campus.

Why is the thought of consuming and purchasing an alcoholic beverage before one reaches the age of 21 perceived so negatively in our culture whereas in other cultures – cultures that appear to not have these problems – children begin learning about and consuming alcohol at a very young age?

For our government to regulate at what age its citizens become consumers of a product is obviously not working.

Kristin Mitchell is a sophomore CCPA major. She can be reached for comment at [email protected].