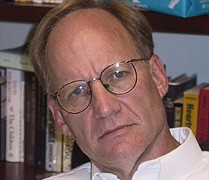

Flournoy brings bite, bark to SMU

Pulitzer-prize winning reporter Craig Flournoy didn’t want to become a journalist after graduation. His goal was to teach history. But Flournoy, newly hired associate professor of journalism, took what seemed his only option at the time and, in the process, made life better for hundreds of people.

The University of New Orleans graduate found himself with a dim-looking future when historian Steven Ambrose told him that there were no teaching jobs in history – not a good thing for someone without much money.

“I didn’t own a suit,” he said. “I looked like your basic mass murderer. I had long hair, full beard and moustache, ski runs through my beard. I was basically equipped to do nothing.”

Desperate for a job, he followed Ambrose’s advice and applied to about 50 newspapers, finally landing a job in Huoma, La.

Raising hell

Since that first job, Flournoy moved away from his home state and established himself at The Dallas Morning News.

In Dallas, Flournoy carved his own niche and in doing so, won numerous awards for ground-breaking reporting on public housing. The most prestigious is the National Reporting Pulitzer he and co-writer George Rodrigue won in 1986.

The Pulitzer, the first the News ever won, was for stories that uncovered patterns of racial discrimination and segregation in public housing across the United States and led to significant reforms.

A later series revealed the horrific state of Dallas housing community Robin Square, resulting in the removal of families from the area. The results, he said, meant more to him than any award.

“It didn’t win a Pulitzer, but it did help about 150 black families in South Dallas get out of an absolute hellhole and get decent housing and, really, a chance at a decent life,” he said. “I consider that story a much greater accomplishment than the one that won a Pulitzer.”

When asked what he thinks about journalism, Flournoy refers to The Chicago Tribune’s definition: “It is a newspaper’s duty to print the news and raise hell.” It’s a philosophy he wholly embraces.

“I believe that you don’t just objectively report the news,” he said. “I believe in reporting with a larger goal, philosophy in mind. You tell people things they don’t know, and hopefully that will make for a better place to live.

“I guess what I’m saying is I believe in hell-raising.”

Doing just that earned him the nickname “Mad Dog” in Shreveport, La., and continued later at The Dallas Morning News, where, he said, he would bark at the phone after a frustrating interview.

“He didn’t just bark at the phone,” said religion reporter Jeffrey Weiss, his colleague at the News. Weiss worked with and nearby Flournoy during the late ’80s.

“For a while, every day around 3 or 4 o’clock, when he felt the need to blow off steam, he’d bark or do bird calls,” Weiss said. “First-time visitors would wonder what was going on. For the rest of us, that was just Craig. The better the story he was working on, the more frequent the barks.

“You could tell when he was having a good day.”

But his success at DMN and winning the Pulitzer didn’t kill his itch to teach.

He earned his master’s in history at SMU and planned to go to Emory for his doctorate when his wife became pregnant. Several years later, news of another pregnancy halted his plans to attend TCU. Obviously, something wasn’t meant to be.

“Then I decided maybe I’ve been barking up the wrong tree. Maybe I ought to try teaching journalism.”

He took a year-long job at Sam Houston State University teaching journalism and advising the student paper for a year, thinking, he said, that it would be boring and all grammar. It turned out to be anything but.

“In the year that I was there, I saw a group of kids that the administration had described as underachievers do some wonderful writing and kick-ass reporting,” he said.

In 1997-98, The Houstonian staff reported on an embarrassing university state audit, on grade inflation and ran a series of stories on student rapes the administration had covered up.

Weiss went to Flournoy’s office at the Morning News every Friday for the latest installment on the Sam Houston happenings and saw the effect his colleague had on his students.

“From his stories and from copies of the papers that he brought back, it was obvious that he inspired some of these students into doing real journalism,” he said.

Perhaps the students inspired the professor as well. Flournoy decided to go to LSU for his doctorate in journalism and to take up teaching full time.

He taught international journalism at the SMU-in-London program last summer, receiving top-notch student evaluations, said Nina Flournoy, his wife and director of the program.

“The evaluations were amazing and stunned me because he’d never really taught before and hadn’t taught international journalism,” she said. “Lots of students wrote that they’d ‘never had this good a teacher before.'”

This semester Craig Flournoy will teach computer-assisted reporting and hopes to complete his dissertation on media coverage of the civil rights movement, comparing coverage by the black press and the white press.

Teaching an old dog new tricks

Weiss has no doubts about Flournoy’s ability to light a fire under his students.

“Whatever course Craig is teaching, what the students are going to have is the experience of being with somebody who is passionate and talented in the world of,” he said. “Plus he’s hugely entertaining and he’s nuts. He knows it, and everybody who knows him knows it, but he uses his eccentricities as a way to prove his points.”

Flournoy’s teaching style reflects his attitude and passion (“Most young people just need a little bit of ass-kicking and inspiration and they can do great stuff.”), but he’s aware of his unorthodox ways and is trying to learn to curb himself.

“I’m not going to bark at students,” he said. “I’m really trying to learn good, academic etiquette…but I’ve basically been paid to be mean for 25 years.”

Chris Peck, Belo Distinguished Chair in the department of journalism, said he has no qualms about Flournoy’s classroom behavior.

“When people walk into his class, they’re going to be engaged – he’s going to grab people and hold on,” he said. “Demonstrating the passion you have for your profession is one of the greatest things you can bring to a class.”

Behind Flournoy’s self-effacing humor, Weiss said, students will find a well of drive and experience.

“He’s got this sort of country charm thing, but below the surface he is ferociously smart and he cares deeply about his work, whatever it is,” he said. “He cares about the journalism projects he did and he cares about the teaching.”

So even though Craig Flournoy may not rescue anyone from the slums this year, he’s finally doing what he always wanted to do – shaping the next generation.

“In one sense, I’m not doing journalism that can make a difference in people’s lives,” he said, apologizing for sounding idealistic and sappy. “On the other hand, if I do it right, I get to make a difference in the lives of young people. People at this university are the whole future of this country. You’re great, you have unlimited potential, you can do any damn thing you want.

“And the reason that I know that better than most professors is this – I’m a hick. I don’t have a very high intelligence, but I somehow became something of a success in journalism.”