Protests have rocked the governments of Tunisia, Egypt, Jordan and Yemen in past weeks, leading to new or partially new governments in three of the four countries. (HELENA BOLOGNA/The Daily Campus)

Protests in Tunisia sparked a wave protests across the Middle East, leading to new or partially new governments in Tunisa, Egypt and Jordan while Yemen’s goverment remains in power. The protests in each country are explained here.

TUNISIA

The Tunisian uprising took the world by what seemed to be mild surprise. Ben Ali ruled the country since 1987, and though his government was criticized by NGOs, major countries such as the United States and France supported it. Its support explains the lack of coverage up until the protests began to shake the country.

In mid-December, 26-year-old Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire in front of Tunis’ provincial headquarters after being denied help there when a policewoman confiscated his vegetable cart and its contents. Though he did not immediately die, his actions set off a wave of controversy in the city, leading to a blunt response by police, which inflamed the controversy into outright riots. Though Ali visited Bouzizi in the hospital in an attempt to quell the unrest, he was not successful and protests continued over poor working conditions, unemployment, corruption and the lack of freedom of speech among other things.

In a televised speech on Dec. 28, Ali warned against “use of violence in the streets by a minority of extremists,” saying that he would punish those who continued the unrest. He was ignored, and the protests continued.

In response, he shuffled around some key positions in his government and pledged to create 300,000 new jobs, though his promises seemed to have no effect on the protesters.

Curfews were put in place, though protesters never followed them. Just days before Ali stepped down, he said he would not change the Tunisian Constitution, which stated that no one over the age of 75 could serve as president. Ali is currently 74, so his statement effectively meant he would not run again in 2014.

On Jan. 14, Ali dissolved his government and declared a state of emergency and fled, handing power over to Prime Minister Mohamed Ghannouchi. Ghannouchi’s reign was shortlived, as it was soon ruled that Parliamentary Speaker Fouad Mebazaa was the constitutionally correct rule; he was given 60 days to organize a new election.

On Jan. 17, Mebazaa announced a “National Unity Government,” which immediately picked up criticism because it still held members of Ali’s former government. This led to a cabinet reshuffle a few days later, but Ghannouchi stayed as prime minister, leading to further protests.

Recently there has been talk of Ali’s allies attempting to spread chaos and take back power. As a result, the new minister of the interior shut down all operations of Ali’s former party. The country continues to increase in stability, but protests still shake the effectiveness of the new ruling government.

EGYPT

On Jan. 25, just weeks after the start of the Tunisian protests, protests in Egypt began. Many of the protesters who took to the streets carried Tunisian flags to show the country’s influence.

The majority of the protests focus on such things as the lack of free elections and free speech, the corruption of the current government, low minimum wage and high unemployment, food prices, the state of emergency laws and police brutality.

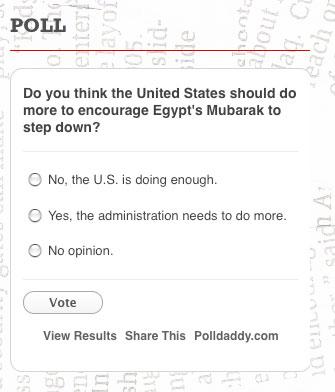

The primary demand of the protesters is the resignation of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, who has been in office since 1981.

Soon after the protests began, the Muslim Brotherhood, the country’s largest opposition group threw its support behind the protests and its members began to join in. The Brotherhood has become a leading voice in the protest.

The death toll rose slowly throughout the first few days of protests, but people were being arrested in high numbers. On Jan. 28, the Egyptian government shut down access to the Internet, texting and mobile phones. Police also issued a curfew, which was promptly ignored by protesters.

The military was ordered to help the police control crowds, but the military took a decidedly more peaceful approach than the police, gaining support and cooperation from the people.

By Jan. 30, the crowds had grown larger and the death toll higher. The military was given permission to use live rounds on the crowds, but refused to do so. Mohammed ElBaradei, a noted Egyptian scholar and former director of the International Atomic Energy Agency, arrived at the center to offer his support.

According to Al Jazeera, ElBaradei said, “You are the owners of this revolution. You are the future. Our key demand is the departure of the regime and the beginning of a new Egypt in which each Egyptian lives in virtue, freedom and dignity.”

The Muslim Brotherhood and other opposition groups gave him their support as the negotiator to form a new government.

On Feb. 1, Mubarak declared that he would not run for another term, though he did not intend to vacate his post early, saying that would lead to further destabilization of Egypt’s government. He also called upon the parliament to change the requirements to run for president and the term limits of the presidency.

The next day, pro-Mubarak groups began to clash with protesters. The supporting forces used violence against the protesters, throwing things like Matalov cocktails and stones. Pro-Mubarak activists also began to attack journalists, leaving over 1000 anti-Mubarack protesters and journalists injured. Western journalists speculated that the two sides might escalate the fight to a civil war.

In the next two days, The Associated Press reported that Egyptians who had been denied cash due to closed banks were offered money and food to stand up against the anti-Mubarak forces.

After his speech on Feb. 1, in which he ordered an “orderly transition” that “must begin now,” President Barack Obama was said to have gone into talks with Egyptian officials over a plan for Mubarak to resign immediately and turn power over to Vice-President Oman Suleiman, whom would lead a transitional government.

In an interview with ABC’s Christine Amanpour, Mubarak said he was “fed up” with being in power, but would not resign because he did not want the Muslim Brotherhood to take power and allow Egypt to fall into chaos. He responded to Obama saying, “You don’t understand the Egyptian culture and what would happen if I step down now.”

Though Suleiman has taken a more active roll in Egyptian politics, by engaging in talks with opposition leaders, many Egyptians are unhappy he continues to be involved. The Guardian reports that many are wary the United States is pushing a Suleiman-led transitional government because it will simply be more of the old.

Egyptians continue to protest Mubarak’s continued presidency.

JORDAN

Protests are rare in Jordan, and its stability is often seen as an exception to the rule in an otherwise turbulent region. Jordan has frequently been labeled by NGOs to be the most stable country in the region. Amnesty International has also consistently labeled the country as having the best human rights in the region, though it still trails most western countries.

But in late January, protests erupted calling for change in the Jordanian government due to complaints of government corruption, denial of rights and joblessness. The protests began in impoverished Bedouin villages, but quickly spread to major cities such as Amman, Jordan’s capital.

According to The Economist, King Abdullah II increased government pensions by 20 dinars (28 USD) a month as a response to the unrest. When that had little effect, he ousted his government and appointed Marouf Bakhit, who comes from the same Be

douin roots of many of the protesters, as the new prime minister.

In a letter to Bakhit, the king instructed Bakhit to “take practical steps, quick and concrete, to launch a process of genuine political reform” and “comprehensive development.” The king said that former leaders had been resistant to change, which had slowed the development of the country, and urged the new prime minister to review the rights and laws that govern the people in order to “address the mistakes of the past.”

But many are still unhappy with the Jordanian government, as they believe that a new prime minister is not likely to produce speedy results. Many protesters continue to call on the king to do away with a part of the 1952 constitution that gives him the right to hire and fire unelected prime ministers.

Though the protests have noticeably slowed, discontented Jordanians still hold rallies calling for political reform and more protected freedoms.

For a more in-depth discussion of the government rehaul in Jordan, visit www.politically-inclined.com.

YEMEN

The protests in Yemen do not pose as big of a threat to the existing Yemeni government as the protests in Tunisia, Egypt or even Jordan do.

Tens of thousands showed up for a “day of rage,” targeted at current Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh due to the poor economy and high unemployment, but tensions have since cooled and few believe the protests to be a significant threat to his leadership.

Saleh has held power since 1978, and has ruled through more tenuous times than these. The Associated Press reports that Saleh “ruled without interruption through Cold War division, civil war, a rebellion in the north, a revived southern secessionist movement and an Al-Qaeda insurgency, among other threats.”

To vote in this poll, visit http