Ra-Sun Kazadi most likely imagined he would be spending his spring mornings and summer nights somewhere on a practice field.

In the shadow of Ford Stadium, tucked in between the buttresses of the old Methodist Church and the outskirts of Downtown Dallas, SMU’s double-fielded practice facility was going to be the backdrop of Kazadi’s first offseason with a real chance to compete for time.

The SMU sophomore safety, who spent 2018 as a redshirt and 2019 sidelined after ankle reconstruction surgery, had everything in front of him. Then the coronavirus shut it all down.

Instead of shuttling between lifts, where his father is Human Performance Coach Kaz Kazadi, and a slate of advertising classes, Kazadi spent his days a 25-minute drive away at his home in Plano. Surrounded by his mother, Monique, and two younger siblings, he occupied his nights perched on the family dinner table equipped with a canvas, charcoal, graphite and an iPad.

While the pandemic largely took away what could have been a chance to carve out time in SMU’s secondary, Kazadi filled the empty hours with another passion: His art and his voice. And as protests enveloped the nation after the death of George Floyd and the coronavirus raged on in Texas, the two converged onto one another.

The 20-year-old began churning out pieces of art with subjects ranging from systematic racism to Kobe Bryant. On Twitter, his art gained traction. It appeared in news publications and slowly, as an unintended consequence, it morphed into a telling undercurrent of a time when words can only go so far.

“It’s weird because [my art didn’t] start out as a political statement,” Kazadi said. “It just turns into one. I draw about what I am feeling. Right now, I am feeling things around this subject.”

‘Somehow it’s controversial to talk about human rights’

Kazadi originally did not want to speak out when Floyd was killed in Minneapolis on May 25. He felt there were already enough voices in the arena, why add to it? What would he even add?

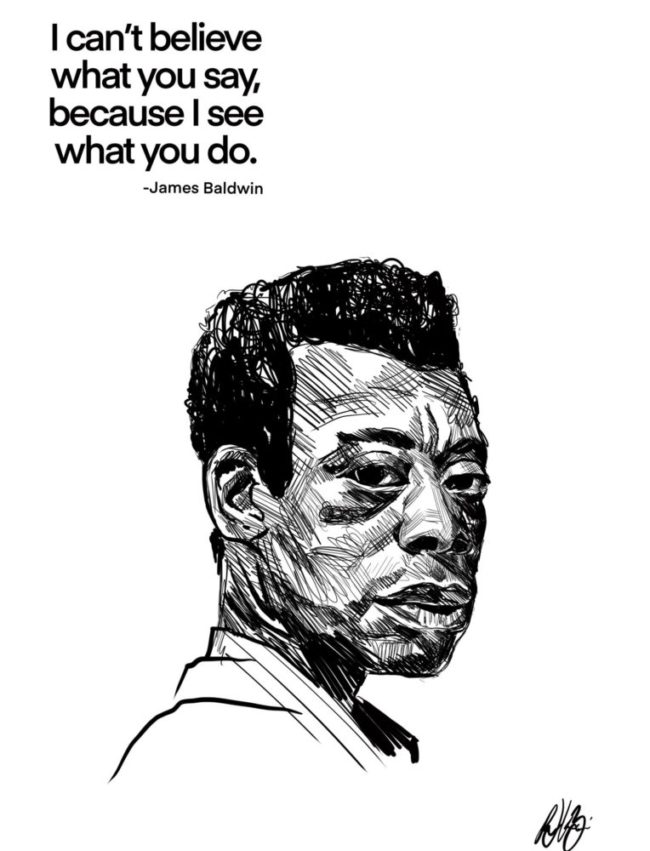

These were the questions rattling around in his head as he spent quiet evenings reading the likes of James Baldwin and other authors that spoke to the issues of policing and systemic racism — Baldwin is a frequent inspiration for his art. One quote in particular, about being patriotic enough to critique America, stuck with him.

“My first thought was that could be really anyone. That could be me. That could be my dad. That could be my friends, my little brother,” Kazadi said. “The fact that it was an alleged counterfeit bill, that you could die for that with someone’s foot on your neck for nine minutes… that really [maddened me].”

That was when the story got more personal. Kazadi’s 18-year-old sister, Isis, was detained at a rally on the Dallas Bridge along with 300 other people. He was not with her when she was taken through custody at the Frank County Courts Building. She had asked him not to come. It was the only protest of three that he not been by his sister’s side.

“It messed with me that the one time I kind of let her go out by herself is the time she had to experience that. Nobody was there with her. That was family,” Kazadi said.

“At the end of the day she was just walking. The fact that you put my sister’s face in the dirt for walking because it is controversial to you, and inconvenience to you, that irritated me,” he finished.

So, he turned to art. He texted Kaleb Mulugeta, a graduated SMU copy writer, saying “I’m doing this.” The two bounced around ideas for hours.

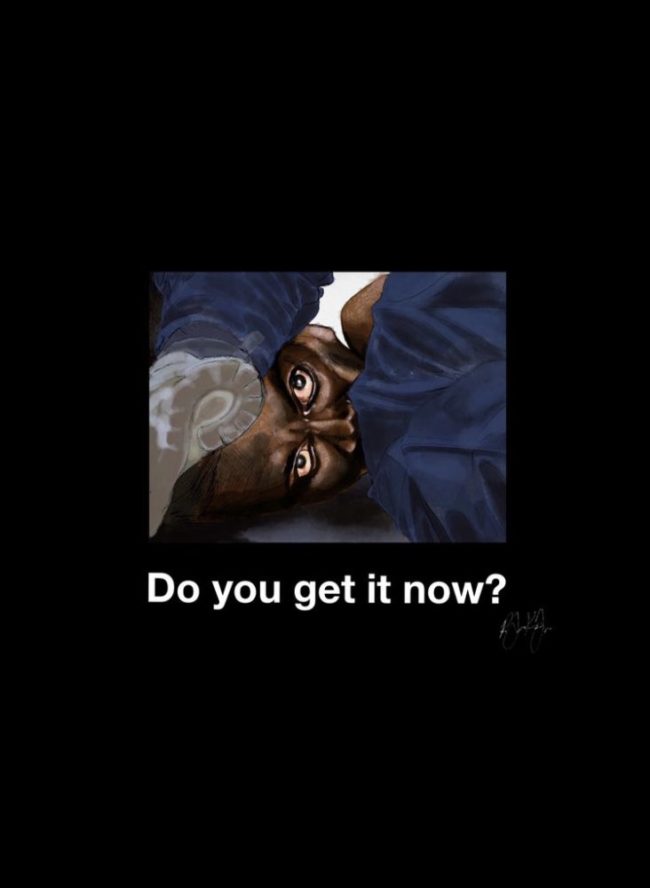

Eventually, he produced the piece “Do you get it now?” The black and blue image, that depicts an African American looking up from under a shoe and a knee, was his vision of the moment.

Just as everyone else tweeted out long paragraphs, Kazadi said, art was his version of expression. The subjects of his art are a conglomeration of his thoughts, not any one person.

“When you think about it, our grandparents fought the same fight… for some reason it is controversial to talk about human rights. It was cool to see people state their side,” Kazadi said.

‘If we don’t speak out, who is?’

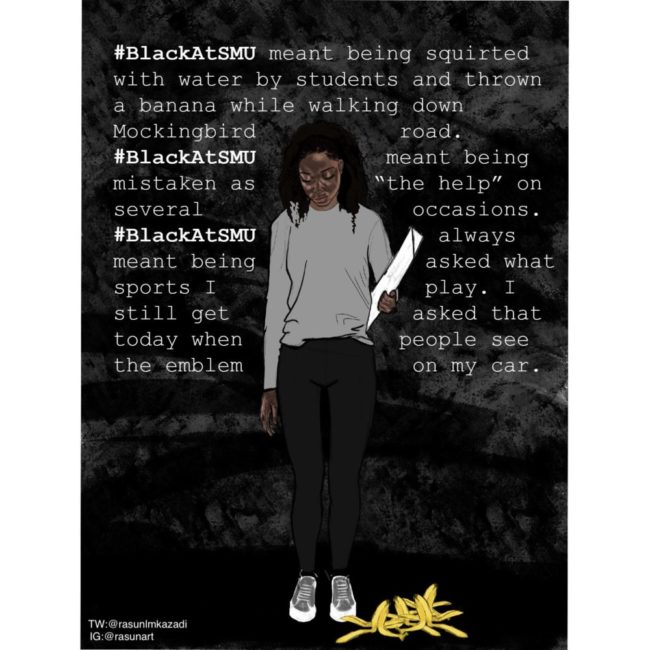

After three weeks of continuous protests hit Dallas and all 50 states, Kazadi again took to art to give voice to another issue that hits more directly at SMU.

In the aftermath of Floyd’s death, SMU students and alumni restarted the hashtag #BlackatSMU to give a voice to Black students who have fought against poor treatment at the university for decades. Kazadi talked with students who were speaking out and attempted to put their experiences into his art —even adorning the piece with their quotes.

To Kazadi, this is the power of art. He wants to use it to lift up other voices.

In reality, though, Kazadi’s art is also about finding his own voice. The issues raised from the #BlackatSMU movement cut deep for him, too. He has grappled with being an African American student-athlete operating at SMU, and University Park. He can recall the racially charged monikers of people saying student-athletes are “lucky to be in school.”

“People try to tear you down for speaking out… it is really racially charged. Like, ‘You should sit down, shut up, and take what you can get. Look where you came from.’” Kazadi said. “People don’t understand that you earned that.”

He is quick to state his position on student-athletes speaking out. He said these types of statements have kept players from giving their opinions in the past. Now, Kazadi thinks, they are tired of it.

“It is weird because [student-athletes] are in a position to where people see us on Saturdays… You feel like you are protected, I’m not that guy,” Kazadi said. “I’ve heard certain guys say that… but we are Black men first. I think us speaking out brings a lot of light to [systematic racism]. If we don’t speak out, who is?”

He has had conversations with teammates, of all races, about it. 30 players, and the entire coaching staff, went to a protest to pass out water. It was all spurred by a couple of players texting on the team’s Teamworks chat about wanting to go.

“Our white players are, well anybody who is not Black, are standing with us and understanding issues. They are saying ‘Oh, I didn’t know it was like that with campus police, DPD, just being Black,” Kazadi said.

‘Got to be about it’

Kazadi never thought of himself as an activist. His art has put him in that category. The coaching staff never knew he was able to draw until he had spent over a year in the program; the sophomore didn’t want to be seen as uncommitted.

Multiple coaches have reached out to him saying they support him. Scott Nady has done so publicly. Kazadi describes Head Coach Sonny Dykes as “all in.”

Former SMU defensive tackle Demerick Gary tweeted out support to his art saying, “Keep standing tall and never be afraid to use that voice. It has volume.”

Dykes added, “Proud of you. Keep working hard and no one will slow you down.”

With the newfound spotlight, Kazadi has used this time to read. A frequent topic of interest is working poverty. As the coronavirus spikes in Dallas County, erasing jobs and incomes along the way, the 5-foot-11 safety has worried about families one check away from homelessness.

That is why, on June 21, Kazadi bought three cases of water and drove to Dallas to handout bottles to the homeless. To him, it is about seeing the bigger picture and changing the system. It is the system that allows people to live “one funeral away” from living on the street.

“For me it is not one issue. It is all the same. It is [less about] treating the symptom and [more about] treating the issue. I’m concerned about systemic racism as a whole and that is a trickle-down thing,” Kazadi said.

The next steps are clear to him. He and his roommates, SMU juniors Jimmy Phillips Jr. and JC Rispress, are working with the SMU compliance office to sell shirts for the proceeds to go to homeless shelters in Dallas and the Equal Justice Initiative. They are also preparing to bring socks and supply bags to the homeless next time they go out.

Said Kazadi, “If we are doing things, people will follow. People will know we aren’t just talking. This isn’t just a fad. This is a movement.”