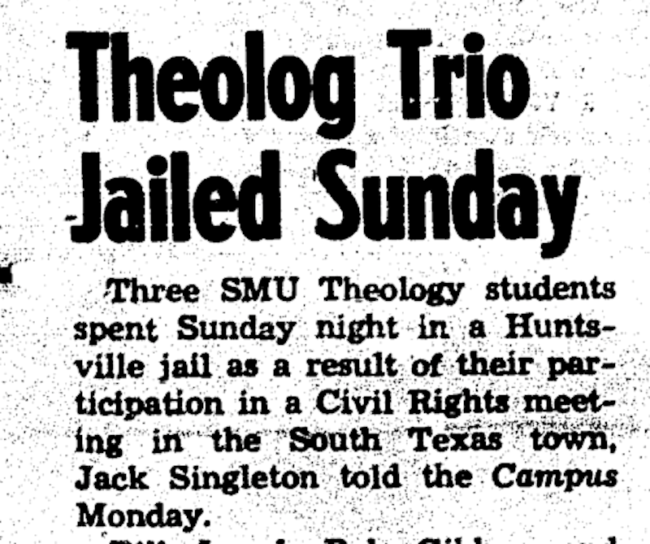

Arrested in prayer on the courthouse steps. An image of hope for some, but on November 14, 1965, it was the reason behind three SMU students spending the night in a small-town jail just 70 miles north of Houston. Bill Israel, Bob Gibbon, and Richard Bond, all Perkins theology students, were among a group of seven SMU students who had visited Huntsville two days prior. Huntsville was a typical, small Texas town of barely 12,000 people that had become the center of a not-so-typical civil rights confrontation the past summer.

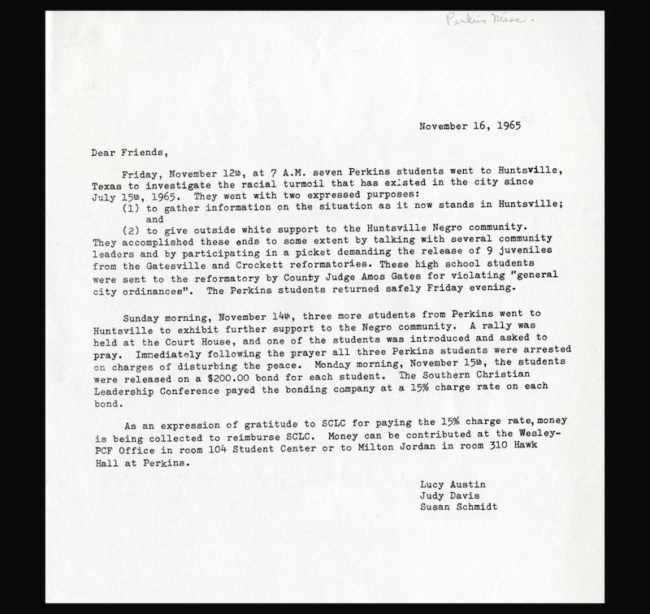

H.L. Boone, fieldworker for Martin Luther King Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), first spoke to a group of SMU theology students about the continuing racial injustice in Huntsville in early November, according to a 1965 article in SMU’s student publication. Their purpose was “to gather information as it now stands in Huntsville,” and “to give outside white support to the Huntsville Negro community” according to an open letter issued by Perkins students after the arrest.

Despite the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, Huntsville continued blocking African Americans from voting and fully integrating into schools and public areas. In response, a group of Texas high-schoolers formed HA-YOU, the Huntsville Action for Youth, in the summer of 1965. HA-YOU, pronounced “Hey you”, didn’t just demand attention in name. HA-YOU’s mission to confront the persisting racial inequality led to a series of civil rights protests that drew support as well as resistance.

Walker County court’s lopsided justice system targeted black people and civil-rights activists of all races with arbitrary charges and inflated fines. Following a sit-in at the discriminatory Raven Café, fifteen hooded Huntsville Klansmen staged their own sit-in the very next day. All 26 original demonstrators were arrested on charges of disturbing the peace with a $200 bail per person, totaling to $5,600. By contrast, the KKK demonstrator and Houston chiropractor, Luther Marce Boyd, who was arrested on charges of being drunk and using abusive language, faced a $28 fine, according to an article in the Texas Observer.

Israel, Gibbon and Bond would face this injustice first-hand when, after delivering a prayer to a rally of civil rights activists in front of the Walker County courthouse, the three students were arrested on charges of disturbing the peace. Despite Boone being the rally leader “the three SMU students were the only ones arrested,” according to the SMU Campus. The SCLC paid the $200 bond for each student the next morning, prompting students Lucy Austin, Judy Davis, and Susan Schmidt to begin their own fundraiser to pay back the organization’s generosity.

Dallas faced a divisive legacy over the course of the civil rights era. Like in Huntsville, resistance was strong and there seemed little incentive for the majority to change. In a later article by the SMU Campus, it was revealed that Rev. Carl Beyer, Huntsville pastor and member of the town’s Bi-racial Committee, warned that the student’s “intentions are good, but they cause Huntsville’s citizens to question not only the university but the Methodist Church as well.”

But unlike many southern cities, communication between white and black community leaders helped bring about a more peaceful change. In response to the events in Huntsville, noted civil rights activist and scholar Larry Goodwyn wrote for the Texas Observer, “A spirit is loose in the South that finds expression in the public acts of young people, but throbs no less meaningfully in their mothers and fathers”.

This spirit was reflected not only in the collaboration between SMU students and the Huntsville activists, but also the greater interracial engagement that kept Dallas relatively calm as the country delved further into racial tensions that ultimately left deep scars.