Nineteen-year-old and recent high school graduate Jesse Patterson’s eyes trace Claire McFadden’s movements as Claire practices her hula hoop trick, swinging the silver hoop around her small frame. For the second time this morning, the hoop flies from 14-year-old Claire’s body, whizzing until it collides with the Lone Star Circus School’s wall and produces a sharp and alarming “dink.” The hoop rebounds off the wall and hits a landing cushion a few feet away situated below an aerial hoop, a metal ring hanging around eight feet off the ground.

To the left of Claire and Jesse, Stephanie Stewart, a Lone Star School instructor, swings nearly 10 feet in the air, feet and arms gripping the yellow aerial silk that suspends her. Stewart watches as her intermediate adult skills students climb the aerial silks after a slow and much needed warm-up on an early Saturday morning. She then leads the women to start side crunches while in the air, grunts and complaints escaping from them. Eventually, each starts to twist herself in different ways on the silk before letting her hands free from the fabric, trusting her safety to the correct implementation of the trick she is attempting.

Claire slowly walks to once again retrieve her hoop. “You need to watch your hand,” Jesse says to Claire, leaning forward on the green bleachers. She continues to offer a more technical solution to Claire’s trick. Determined, Claire once again works on her trick, and Jesse relaxes to watch once again during her first break all morning.

As she has done every Saturday for months, Jesse is spending her Saturday at Inwood Soccer Center, home to the Lone Star Circus School. The parking lot for the small sports complex seems like a dead-end, framed by storage sheds on one side and a bubble-looking tent over the soccer field to the other. Inside the narrow concrete hallway, the entrance to the school gym can easily be overlooked if not for the Lone Star Circus logo on the windowless door. But the gym is anything but forgettable. Bright red carpeted floors, blank walls, hanging silks of rainbow colors, trapezes and hoops fill the interior. From an outsider’s perspective, the gym seems like a color-clashing chaos, but to Jesse and others in the school this gym is the practice field of their future.

Jesse, an aspiring circus professional and dedicated circus student, started her journey eight years ago, a career path that not even her parents could have predicted for her. Jesse lived in a family of four with her parents and her twin sister, Catherine. With no performers in her family, Jesse’s primary exposure to circus came through her studies at Dallas International School (DIS), a private school in North Dallas focused on a global education.

DIS offers after-school circus practices through Lone Star Circus School for students in addition to sports and other extra-curricular activities such as soccer and yoga. The school holds classes in an on-campus gym in the afternoon. At the age of 10, Jesse decided to join the program after watching several performances by her classmates. Jesse eased into the program by taking one course a week; however, due to her height, she was placed in a level with older and more advanced students, which was a challenge. “Being around people who were a lot better than me made me want to be better,” Jesse said. Within half a year, Jesse felt the spark of performing that drove her to continue.

Jesse’s mother, Cynthia Patterson, recalls Jesse’s ambitions from an early age. At around the age of 11 and just a few months after beginning classes with Lone Star, Jesse rode in the backseat of her parents’ car as she excitedly told her parents her dreams and goals in circus. Her parents, supportive yet amused at their young daughter’s determination, laughed as Jesse continued to speak. Jesse, irritated by her parents’ reaction, said, “I don’t think you’re taking my career choices serious enough.” Jesse, however, takes her circus development very seriously and now considers her practice as a job instead of a hobby. “She hasn’t really wavered, and she’s been very focused on her objectives,” Patterson said.

Dallas Lone Star School has been training students since 2006. Fanny Kerwich, an eighth generation performer from a well-known French circus family, started the school after moving to Dallas. The school offers 21 different classes on every day of the week except for Saturday in specialties ranging from aerials to juggling. The school even offers a toddler course for ages three through five.

Grace Farrelly, a 10-year-old student at DIS, begged her mother to start circus after watching a professional show when she was five. “She never looked back,” Katie Farrelly, Grace’s mother, said. “She loved it from the beginning.” Farrelly watches from the bleachers as Grace practices her piece for the school’s upcoming spring performance, which begins with Grace in an aerial loop, reading a page of a newspaper as she climbs on the loop.

Even though aspiring performers like Jesse and Grace approach their practices wholeheartedly, parents face special challenges to support their children. “Mostly, I’m concerned about whether or not she could make a living doing [circus], and safety,” Patterson said. Jesse’s mother and father have both encouraged Jesse to pursue an untraditional degree plan through an online university while striving for the circus, and Jesse has agreed to take courses for a business degree while performing. “I am always pushing her to get a master plan to get direction,” Patterson said.

Success in the circus, however, depends mainly on the work ethic of the individual, because any school can offer only so many classes. “Here you can do anything if you are willing to give what it takes,” Kerwich said. Kerwich knows the commitment level that the profession takes. “It is a lifetime sacrifice,” Kerwich said. “You give everything you have for five minutes on stage to touch people in a way that no other act can.”

Kerwich recalls Jesse’s early dedication. “Jesse was from day one the kind of kid who you show one trick, and she would come back to class and learn three.” Jesse challenged herself outside of classes by watching other performers’ tricks on sites like YouTube and used these ideas to develop her own style. Despite noting Jesse’s talent, Kerwich watched from afar as Jesse developed in her training before starting to work with her. “I’ve been the meanest to her than anyone else,” Kerwich said, waiting to see if Jesse’s passion will stand the test of time before investing her time in Jesse’s training. Eventually, Kerwich mentored Jesse after she adopted the hula hoops as her specialty.

“I started after seeing a hula hoop act at a show,” Jesse said. “I picked up a hula hoop at my grandmother’s house and started doing it.” After the previous hula hoop artist that Kerwich trained, Raphaele Daubois, left Lone Star to pursue her career, Daubois then passed the hula hoops to Jesse, who then continued as the top hula hoop performer at Lone Star.

During Jesse’s freshman year at Ursuline Academy, she stopped taking courses at Lone Star School and transitioned to coaching while still working with private coaches for specialized training in hula hoops. Jesse remembers fondly her training with Mat Plendl, a self-trained hula hoop artist based in California at the time. Jesse worked with him over Skype. “He just sort of sat there with his tea and watched and showed me if I was doing anything wrong,” she said. She also performs at different shows across the country, such as the Worldwide Circus Summit in Massachusetts, the Austin JuggleFest or the Chicago Contemporary Circus Festival. Despite the time commitment, Jesse says that traveling is her favorite part of what she does.

Last spring, Jesse co-directed the year’s Lone Star Circus Annual School Program. “Jesse is a purist, and I am too,” Kerwick said. “I know she’ll pay attention to proper technique, so I’m letting her take over.” For this role, Jesse works closely with the younger trainees to choreograph and practice their routines during her class sessions. Jesse has taught at the school since 2012, which is common as students progress to high levels.

At her Saturday class, Jesse plays “You’re the One that I Want” from Grease on loop, which was catchy the first time and not quite as much the tenth, while four elementary-school-aged girls perform a trapeze act. She occasionally stops to offer choreography tips to the girls, her face showing her care and concern for each of her students as they pull themselves onto the raised trapeze. Worry fills her eyes as one of the small girls performs a trick that even she had trouble with as a beginner. The small performer pulls herself to stand on the trapeze and then holds herself upside down solely by grasping the ropes. Jesse moves forward as she urgently asks her partner, “Spot her!” Jesse thinks back to herself at that age. “I was emotionally not allowing myself to do [the trick],” she said. “I was so scared of the height that I didn’t trust myself to go upside down.” To this day, Jesse prefers ground tricks compared to aerial stunts.

While the students’ stunts come with risk, Kerwich notes that no students have been seriously injured since she opened the school. “I’ve never seen someone walk away from the circus after a fall,” she said. “In fact, I think they like the adrenaline, and they just get back up and try again.”

Each performer endures the pain of practice and the risk of injury to enjoy the satisfaction of being on stage. “You share a moment of humanity in life, and you never know if it will happen ever again,” Kerwich said. Jesse, on the other hand, maintains a strict concentration during her performances. “I can’t tell you anything I think of,” Jesse said. “It’s one of those things when you’re completely in the present.”

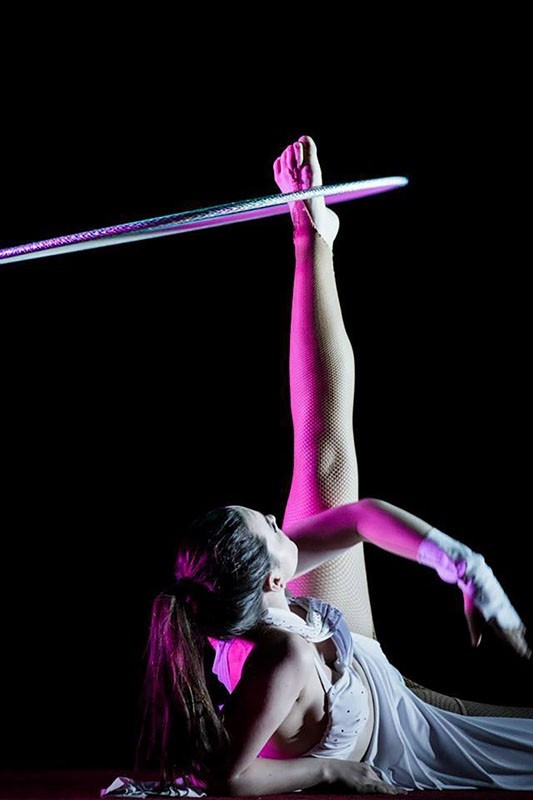

For Jesse, a day on stage consists of one of her five-minute, choreographed performances with each movement fluidly connected through tricks and transitions. She currently performs three acts: the classic and dramatic Ginette, the upbeat and energy-filled Swing Hoop Swing and the sexual and mysterious Deliverance. Deliverance is currently her most advanced act, consisting of pushing her silver hoops to every part of her body with constant control of its momentum and position. Her tricks also include kicking her hoop off her foot to her hands and spinning seven hoops on all different limbs. Her final trick usually includes twirling a life-size slinky around her body. These tricks may be learned from her coaches or offshoots of other professionals that she watched, yet her transitions, music choice, costume and demeanor make them her unique show. Not one for spontaneity, Jesse performs the moves in a concentrated, daze-like state, only changing her routine to respond to an engaged crowd. A look of accomplishment and pride erupts on Jesse face each time the audience appreciates her tricks with applause.

With her students, Jesse focuses on increasing stage presence, a useful quality for any career, instead of focusing on proper circus technique. “[Teaching] is one thing that I really like about circus because it can really change and transform people,” Jesse said. Students like Grace have experienced this transition. “[Circus] gives you confidence and poise to present yourself,” her mother said. “As Grace has done performances each year, she’s grown more confident with herself.”

Likewise, Kerwich finds fulfillment in seeing the moment when a students’ eyes spark as they find their passion, just as Jesse found her future career. “For me, it’s everything,” she said. “I’m living for that moment because I know my mission is accomplished.”

Jesse has seen this transformation in a student she privately teaches, Claire McFadden. Claire began at Lone Star when she was six after viewing a few shows and wanting to give the circus a try. She now plans to pursue a professional career in the circus. “Now that I’m graduating, I was looking for another hoop girl, and I think Claire is going to be that girl,” Jesse said. In the same way that Jesse had her hoops passed down by Daubois, Jesse plans to pass the responsibility to the aspiring Claire.

Eventually, Jesse rises to collect her materials from her morning classes. She walks through the gym and gathers her hoops scattered across the floor, along with her jacket and bag, occasionally turning to watch Claire as she flips the hula hoop around her body. By this time, the toddlers’ class is just beginning and small, barely walking children start running across the red carpet of the gym and hiding in the aerial silks. Stewart continues her adult class, whose students are now practicing complicated flips in their silks. Kerwich sits and watches from the bleachers, occasionally offering advice to students or laughing at the little toddlers trying to do a flip in the silk with the assistance of their instructor. She points to a little girl in a pink and purple gymnastics suit. “She just started today,” she says. “Look at the way she just feels at ease with that silk.” The small girl stands on the knot of a light blue aerial silk, playing peekaboo in the fabric. Two other children start bouncing on a landing pad while a boy throws plastic rings, completely oblivious to the requests of his teacher.

Claire, on the other hand, practices on the ground. Her body moves in sync with the hoop; it rolls off her fingers as if it and they are one. Jesse walks by and offers yet another tip before walking to another room. “I’ll work really hard on this. I promise,” Claire says as Jesse walks out the door. She concentrates on her hoops for around an hour after her class ends. Eventually, she checks her phone to see if her dad has texted stating his arrival, and she begins to pack her stuff. On her way out, an old 2011 Dallas Morning News clipping taped to the wall catches her eye. She stops to stare at an image of the hula hoop artist Daubois for just a few minutes. She then leaves the familiar silks and red carpet to return to the regular world, waiting for the time to once again go home to her hoops.