Author’s note: Due to specifications for the RA role prohibiting students from speaking to media sources, all RA’s names and identifying factors have been removed from the article. It is because of this clause that this article is even more important: Resident Assistants are unable to speak up for themselves without fear of losing their jobs.

Historically, the Resident Assistant (RA) position at SMU has been touted by the administration as one of the most prestigious leadership roles on campus, carrying with it the responsibilities of caring for other students and modeling leadership and adherence to SMU community guidelines. However, the attitude toward the role has drastically shifted since the onset of the pandemic.

What was once an energizing, community-centric job with great financial perks evolved into front-line work, in which RAs were asked to become the primary enforcers of SMU’s coronavirus policies in the Student Code of Conduct, plus the addition of two desk hours weekly. These changes have resulted in experienced RAs resigning, Residential Community Directors (RCDs) leaving in droves, and students feeling unsupported within their residential commons. In early April, two more RCDs announced their resignation in addition to the many who resigned last semester.

Why do people become RAs?

Simply put, the RA role is difficult. Students in the role are expected to serve as resources, friends, and mentors for their peers within the residential commons, all while enforcing unpopular community guidelines. The SMU website credits the role with creating “lasting and meaningful connections with fellow students, staff, and faculty,” “a greater understanding of and pride in the greater SMU community,” and “enhanced leadership skills and an appreciation for servant leadership roles.” While all of this is true, it is also important to keep in mind that students in this role are employees of the university.

Students apply for the role for many reasons; among them developing leadership skills, building community within the residential commons, or simply because they want to be an RA. However, a majority of students apply for and take the job because the RA position covers room and board at SMU – a cumulative $17,658/year.

“I became an RA for the free room and board, to live in a single on campus, and so I could do events for my floor. My parents expected that I’d figure out a way to pay for room and board,” said one former RA*.

He quit after the role shifted during the pandemic.

“My RA was a role model to me freshman year, and I always went to him for everything,” said another senior RA about the role. “He was a very valuable resource. I looked up to him. I wanted to create that same sense of belonging in the role.”

When asked if he felt as if he had created that sense of belonging in the role, he shook his head in what seemed to be defeat. “I tried,” he said. “But COVID has been really tough to make that happen.”

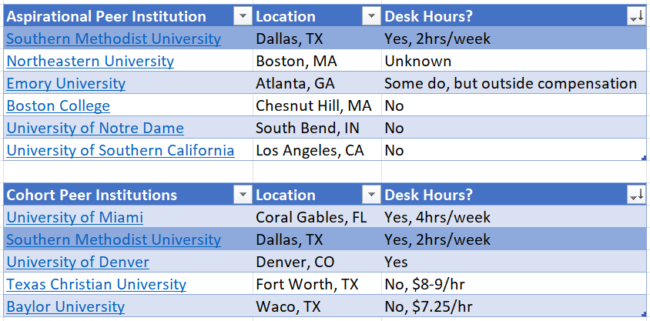

According to the National Survey of Student Engagement, first-year students who live on campus are more engaged with their peers, which leads to a higher college experience satisfaction rating, and seniors who live on campus are more engaged with advisors and faculty than their off-campus counterparts. However, housing costs at SMU are high compared to peer and aspirant institutions.

Highlighted in the darker blue above, SMU sits above all of its cohort peer institutions and below only one of its aspirational institutions. While SMU is generous with financial aid (75% of the student body is on need- or merit-based aid), the majority of scholarships do not include the cost of room and board. Students who wish to make the most of their SMU experience must find a way to pay $17,658 for housing for the two-year live-on campus requirement, and many students choose to do so through the RA position. However, this encourages students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds to apply and become dependent on the job. Some RAs feel trapped in what is now an unsatisfying job.

“My motivation to become an RA was mostly financially, but I also thought it’d be a great leadership development experience,” she said. “I can’t quit – otherwise I wouldn’t be able to live on campus and be involved with the things I love.”

How has the role changed?

The pandemic exacerbated the unfavorable parts of the RA job like policy enforcement and essentially eliminated the fulfilling elements like community building and interactions with residents. While events were allowed in the August of 2020, SMU’s COVID-19 guidelines prohibited events inside and food and required social distancing, among other things. Guidelines relaxed throughout the school year, but the precedent had been set.

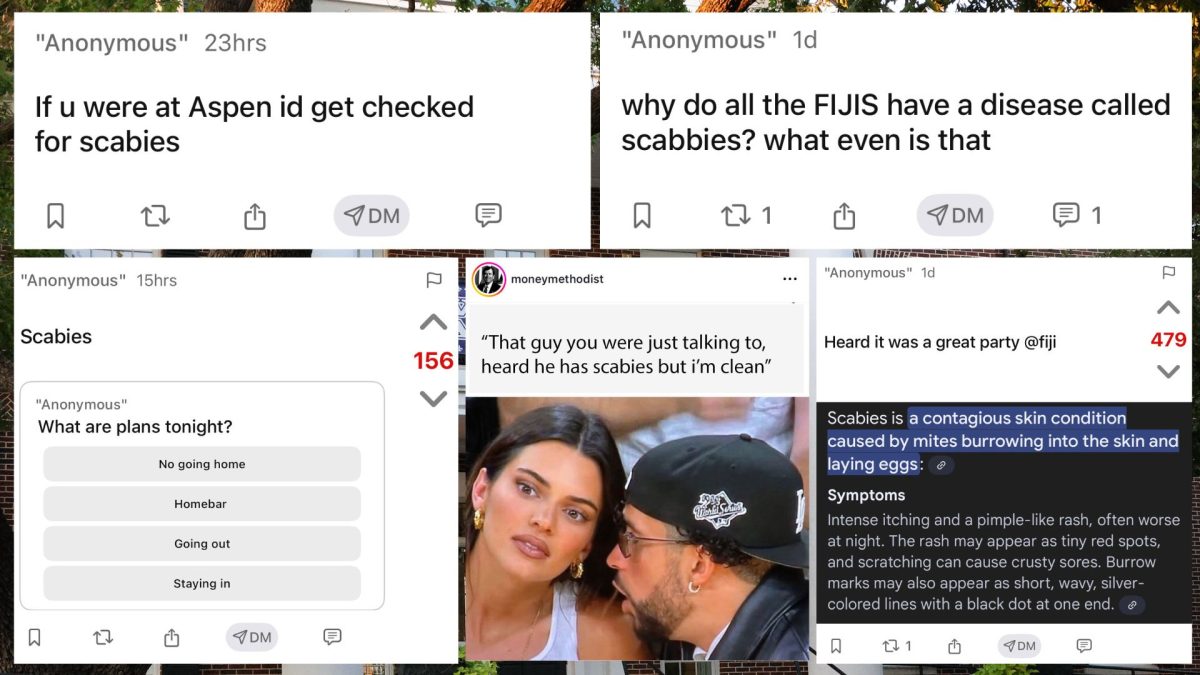

Comments on social media, including the Instagram and YikYak platforms, are continually made about RAs in the residential commons comparing them to police or calling them “narcs.”

“Every single time I was in the hallway interacting with residents, like 100% of the time, I was enforcing something,” one said. “RAs were people nobody liked, where they used to be trusted mentors in the commons.”

The responsibility of enforcing pandemic policies (e.g. masks in the residence halls, no guests) was thrust upon the RAs in August of 2020 at RA training. One RA says the change in expectation was not relayed until they were on campus.

“When I signed my RA contract, the pandemic had not hit. At the time, I understood the role to be a difficult position in terms of making sure peers on campus were following the student code of conduct and other rules SMU provides for,” they said. “What the role turned out to be was somewhat like the RAs were on the front lines of COVID.”

This put a strain on the relationship between RAs and residents at the outset of the academic year. RAs attempted to find a balance between enforcing these policies and offering a helping hand but more often than not, residents viewed them as the enemy. Residents find this sentiment hard to shake even as coronavirus restrictions ease within SMU and Dallas, and current RAs describe a remaining animosity where there used to be trust.

“The biggest difference so far this year is probably not having to enforce the mask policy. When we had to enforce it, there was simply not a community within the building. It’s a totally different world for residents and RAs now that they don’t have to do that,” a current RA said. “We’re still not back to where we were in terms of community, but it’s better than it was.”

Current Issues with the Role

Beyond the inevitable change due to the pandemic, many RAs are upset by the new desk hours: for two hours per week they are now contractually required to work at either the Virginia Snider or Armstrong area desks. These desks are open from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. seven days a week – completely staffed by RAs. There, RAs assist students with lockouts outside of on-call hours by assigning temporary student IDs and physical keys.

“It’s not so much the addition of desk hours themselves,” a current RA said. “It’s the fact that they never asked for our input on how to staff it, and it took away a work-study opportunity from students who needed it.”

The area desk was formerly staffed with students through the Federal Work-Study Program, and when Residence Life and Student Housing (RLSH) decided to reassign that responsibility to the RAs, which was not communicated to the students who held the FWS roles. That lack of communication, of course, is another frustration that RAs have with RLSH.

“A major issue has been the lack of dialogue between RAs and administration. And even more than that, when they do listen, it is more performative than it is action-oriented,” a current RA said. “It speaks to a lack of understanding of how the job currently operates.”

The lack of transparency and communication is a common motivation for RAs and RCDs who choose to leave.

“The menial tasks and responsibilities increased without any increase in compensation, and I was incredibly frustrated with the RLSH staff in general,” said a former RA. Now, in his senior year, he attributes his increase in happiness to living in an off-campus apartment. “The role put a lot of the burden of policy enforcement onto the students, putting them on the front lines of keeping campus safe during COVID.”

Given the cost of housing at SMU compared to others, it is not unreasonable that students must complete two hours per week at the desk. However, poor communication between RAs and RLSH staff is a larger issue that must be addressed.

Looking Forward

As the next class of RAs prepares to come into the role, new concerns arise.

“I want to make sure I’m treated as a person first, not a worker. I’ve heard stories of before and after COVID, and I just hope I’m treated with respect,” an incoming RA said. “That being said, I’m optimistic that we can get the role back to where it was.”

In the fall, SMU Student Senate proposed a $5,000 per semester stipend to be allocated to RAs to “help alleviate financial, mental and physical burdens with having to work the area desk,” among other things. This specific proposal did not pass. Other groups must continue to advocate on behalf of RAs as they are unable to advocate for themselves.

“This job is a necessity for a lot of students – the worry is that if you speak up and stand up for yourself then you will lose that financial security,” a current senior RA said. She feels like it is easier for her to speak on the issue with less than two months left in her college career, but she knows that others are far more dependent on the role.

At the end of each interview, I asked a very telling question: Would you recommend the RA role as it stands right now? Here are those responses:

“Would I recommend the RA role as it stands right now? Depends on how bad you need the money.”

“I wouldn’t fully endorse the RA role as it is now. But I definitely would’ve before covid”

“I would recommend it in a financial sense, but if they didn’t need the job to cover room and board, I wouldn’t.”

“If you need it, I’d recommend doing it. But I wouldn’t go out of my way to tell people to be an RA.”

My Experience

I served as an RA my sophomore year in Cockrell-McIntosh Commons, and like the other RAs above, I chose to become an RA for several different reasons including looking up to my former RAs, reduced cost of living, and leadership experience. However, my main motivation for becoming an RA, as simple as it may be, was to help further the community I felt within the residential commons my freshman year. As a sophomore in the role in the 2019-2020 school year, I fully expected to ride out the job through my senior year.

However, when the circumstances of coronavirus changed the expectations of the role, I found myself resenting the job I had once loved. The aspects of community building within the commons had completely disappeared, and, as other RAs said, we were expected to police residents instead of acting as helping hands or role models. Though I have great respect for many of the individuals within the RLSH Office, I believe that an undue burden was placed on the students within the RA role. I chose to leave the role to prioritize my mental health, academic and career aspirations, and relationships with my peers.

Thankfully, my family was willing and able to financially support me when I decided to resign from the RA role – though this is not the case for many students who serve in the position. The role, as it stands right now, jeopardizes the mental health of student employees of the university, and SMU administration and Residence Life and Student Housing must do whatever they can to make sure the RAs are taken care of. Oftentimes, RAs are the first lines of defense for students: they are trained on signs of suicide and depression, social and academic withdrawal, and what to do in case of alcohol poisoning. SMU could not operate as it does now without the support of RAs. If RAs are not supported, issues like a student’s mental or physical welfare that are commonly spotted by RAs will fall through the cracks. And the student experience and well-being of SMU students will take the brunt of the fallout. Honestly, it already has. The resignation of RAs and RCDs alike is indicative of a larger issue or disconnect between RLSH and its employees.

While there is no straightforward path to a solution, RAs at a limited number of other schools have been successful in forming unions or advocating for better conditions. Students at the University of Massachusetts Amherst formed a union in 2002, and student employees at George Washington University attempted to as well. While some choose the unionization path, RAs at Brown University organized, protested, and went on strike to advocate for better working conditions. Cornell University RAs and the University of Michigan RAs went on strike specifically regarding COVID-19 changes. There has been no tangible change within the RA role at SMU despite continued outcries of poor working conditions.

Recently, RLSH released an email to current RAs about concerns with the role and how they will attempt to address it. While admitting that the role has issues is a great start, there are still strides to be made.

Being an RA was one of the most formative experiences in my personal and leadership development, and it offers students and RAs alike a fantastic peer support system. However, while the university tries to sell the position as a leadership position, students are still employees of the university, and they deserve privileges as any other employee does. It is my hope that the role returns to how it functioned before the pandemic hit, but that cannot happen without reform of the role and a reset in the relationship between RLSH and RAs.

The Daily Campus welcomes opinion contributions from students, faculty and community members. Submissions should be no more than 1000 words and are subject to copy editing. Please email submissions to smudailycampus@gmail.com, and include a cell phone number and a short biography. All pieces submitted to and published by The Daily Campus are under the publishing and editorial purview of the paper once published.