King races history of rights campaign

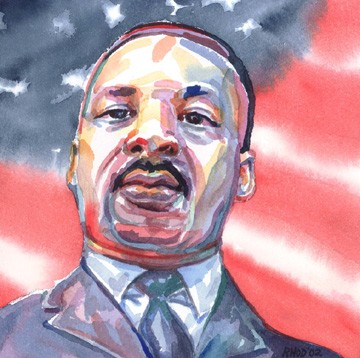

Originally published March 23, 1966, this article is reprinted to commemorate Martin Luther King Jr.’s 74th birthday

As policemen swarmed, a record McFarlin audience jammed both McFarlin Auditorium’s aisles and balconies Thursday to hear the Rev. Martin Luther King say civil rights has come a long, long way, but it still has a long, long way to go.

In a voice that gained momentum and feeling as he progressed, the Negro leader traced the history of the rights movement and emphasized the necessity of facing the problem now to his 3:30 p.m. convocation audience.

A participant in last year’s Selma and Montgomery marches, King said the future of integration was “on the lips of millions.” Any realistic answer to the question of progress in race relations affords “the extremes of deadly pessimism and superficial optimism,” he added.

Tracing the movement’s history from the Negro’s first arrival in 1619, brought here as slaves against their will, the Nobel Peace Prize winner declared that the Dred Scott decision “clothed slavery in garments of righteousness.” With a history of enforced inferiority behind them, industrialization gave the Negro a new chance for re-evaluation.

In the new struggle for freedom, Negro voting has gone up, and the number of lynching has gone down. According to Dr. King, the average employed negro earns four times more today than he did 10 years ago.

“We’ve broken loose from the Egypt of slavery, we’re in the wilderness of segregation and on the borderlands of integration. The former Time man-of-the-Year stressed, mentioning “pockets of resistance such as the 52 churches burned in Mississippi in the past 18 months.

But too many negroes still live on the “periphery of life,” which they see as a long, desolate corridor of no exits, King continued. There are still not enough Negroes voting or job opportunities available, and too many are still “perishing on a lonely island of poverty on a vast ocean of prosperity.”

Two myths cloud our thinking in the current struggle, King added, citing time, which most people feel will heal the problem. “The time is always right to do right,” he said, and “although legislation,” which people see as another cure-all, “can’t change the heart, it can change the habits.”

The Baptist clergyman explained his philosophy as one of non-violence, which he called the most potent weapon of the oppressed, because it completely disarms the opponent. It can turn a “dungeon of shame to a haven of dignity” by achieving moral ends through moral means, by meeting “physical force with soul force.”

“A man without something to die for isn’t fit to live,” King announced, as he interjected that the love effort must be the focal point of all strivings. Not an emotional love, but what the Greeks called agape, an understanding, creative good will which each man extends to mankind because of God’s own love.

King, a NAACP member radically opposed to the Black Muslims, urged his listeners to “become involved participants instead of silent onlookers.”

“No lie can live forever,” King concluded.