Antong Lucky was only a year old when his father was sentenced to 50 years in prison. In the absence of his father, his mother worked long hours and multiple jobs to provide for his family. Lucky often found himself on his own, and learned he had to be tough to survive in the violent neighborhood he lived in.

After being involved in skirmishes with youths from newly formed gangs in other neighborhoods, Lucky and his cousins founded one of the first blood gangs in Dallas. By the time he was 20, he found himself in a courtroom where the judge labeled him a “menace to society.”

During his time in jail, Lucky turned his life around. Since his release from prison, he has been working in the nonprofit space. He now serves as the CEO of Dallas-based nonprofit Urban Specialists, who specialize in the recruitment, training, and deployment of community change-makers to combat crime and other social issues in the Dallas area.

Lucky said the formation of the group stemmed from thinking about his family.

“I was thinking about my newborn daughter,” Lucky said. “It birthed this desire to go back and clean up and provide for young people growing up in neighborhoods.”

He has participated in multiple yearly collaborations with the Dallas Police Department and other social justice organizations to ensure the betterment of youth in Dallas through mentorship and education.

He is planning to do it again this year, backed by now-established law Legislative Bill 3186, dubbed the “Youth diversion plan,” which aims to divert minors alleged to have committed misdemeanors punishable by fines to alternative programs aimed at rehabilitation.

“I think it’s good, and it’s restorative,” Lucky said. “I believe that anyone and everybody, regardless of what they’ve done, is entitled to be redeemed.”

Lucky will speak at SMU on Feb 28 as part of the Bridge Builder Lecture Series on community building and development.

The new law would present the opportunity for erring minors to participate in drug education programs, work/job skills training, academic tutoring, mental health and counseling sessions, and community-based services. All district and municipal courts in Texas are required to adopt the diversion plans.

In addition, the bill allows for the appointment of a youth diversion coordinator to assist in administering diversion plans. Barbara Kessler, Communications Director of the Texas Juvenile Justice Department, believes this law could assist in keeping some youth from falling deeper into criminal behavior.

“The courts can help these kids early and still hold them accountable, without having to impose a court fine or court conviction,” she outlined in a statement. “This law makes that easier to do at the municipal court level and should help invigorate diversion efforts.”

Lucky, during his few stints in the juvenile system, participated in a diversion plan similar to those outlined in the bill, and was sent to a state-run reformation school for juveniles in Pennsylvania at 16. As a student in the talented and gifted program in his high school, he was identified as a teen with potential and given a second chance by being sent there.

Lucky wishes he had taken more advantage of the opportunity and believes that the new law’s enactment is a step in the right direction that could save a lot of kids with stories similar to his.

“I’m a prime example of it,” Luck reiterated. “Many kids are being raised without the support system that helps them evolve into the best they can be. I think [HB 3186] is super important.”

The introduction of the new bill brings Texas’ administration of juvenile cases closer to the norm in most other states. Typically, these cases are heard in juvenile courts, not in municipal courts, leading to lessened sentences for minors facing charges.

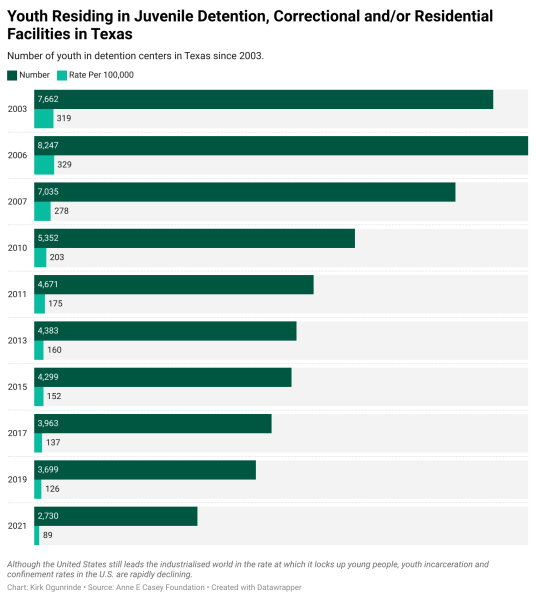

The U.S. Justice Department’s Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, reported that from 2000-2022, the number of youth in U.S. juvenile facilities fell 77%, and youth under the age of 16 accounted for more than half of all cases.

According to Brett Merfish, director of youth justice projects at Texas Appleseed, a non-profit based in Austin, the alternative programs have the potential to be increasingly beneficial to youth in Texas.

“This is going to help kids not have stains on their records when they don’t need to,” Merfirsh said. “We know that intervening with mental health programs and other kinds of treatment can help, so let’s do what we know works.”

Now, as a proponent for change in the Dallas community, Lucky’s non-profit Urban Specialists provides resources like OGU, a training experience that utilizes local influencers to use their platform to inform youth; USC3, a networking event where community leaders collaborate to foster youth initiatives; Community Business Academy (CBA), which assists minority entrepreneurs to establish their businesses; and UniteVersity, which provides locals with an on-demand interface for learning how to enact change in their communities to youth in the Dallas community.

Lucky’s team also provides nightly neighborhood watches, community clean-ups, and block parties – all to keep Dallas youth off the streets and away from crime. He believes social justice organizations and nonprofits have an important role to play in fostering the efficacy of legislation such as the one outlined in HB 3186.

“Nonprofits are critical to neighborhoods,” he said. “I have so many success stories of young people who come from neighborhoods like I come from, who I’ve mentored and are now successful and enjoying life.”