When you reflect on the Declaration of Independence, your mind likely moves directly to the “self-evident” truths or to the “inalienable” rights. What comes next, however, we often forget.

President Thomas Jefferson continued on to explain that governments must derive their power “from the consent of the governed” and that it is the role of the people to “alter or abolish” a government that becomes “destructive” or unjust.

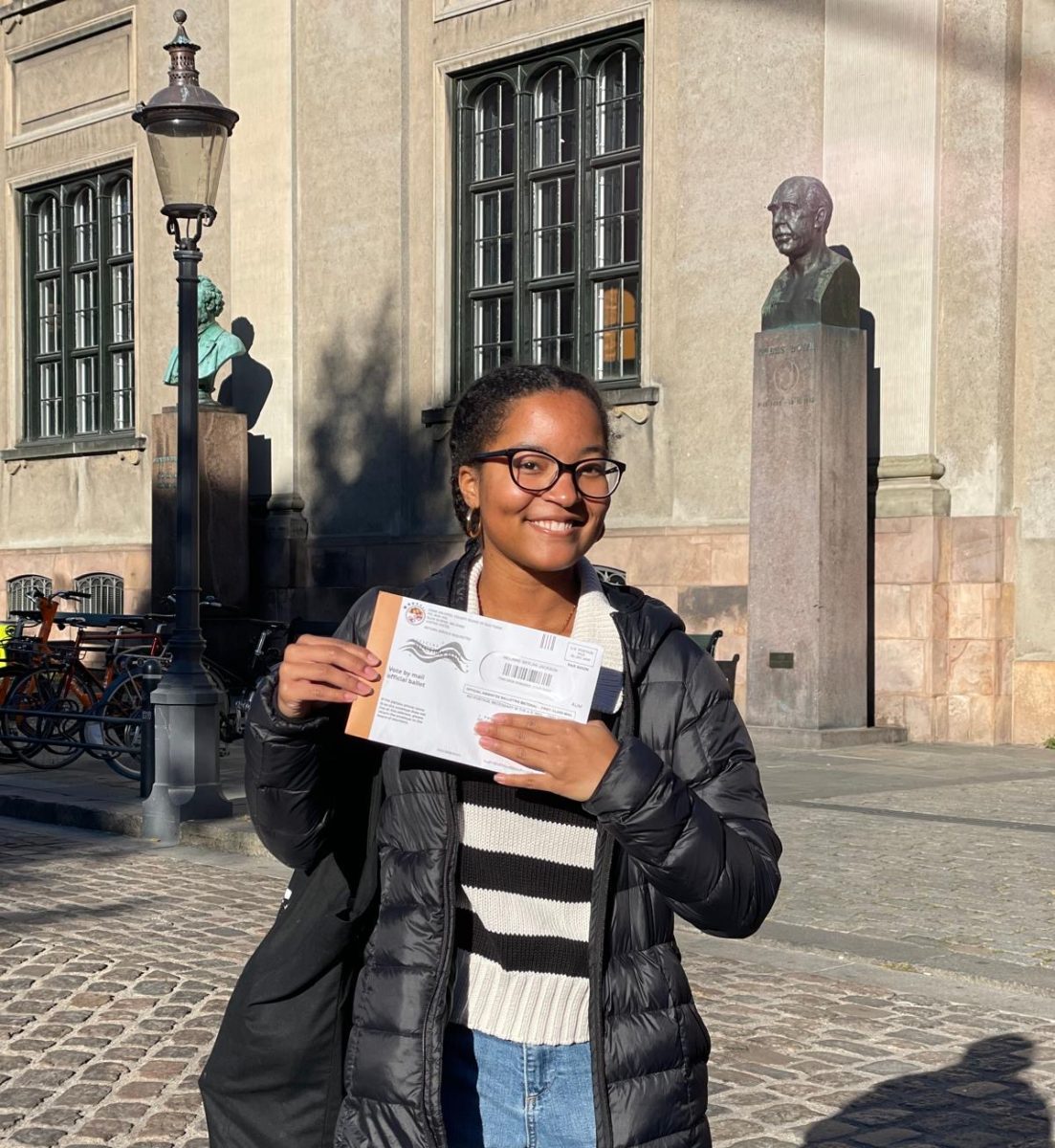

Campaign season is the time of year when the “consent of the governed” comes into question and when the voting populace decides whether or not to “alter or abolish” our elected officials’ tenure.

From now until the November midterm elections, we will be subjected to the lunacy of political campaigns. Prepare yourself for intense commercial advertising, stake signs galore, political interviews and unveiled scandals.

This is what the electoral process has become: a drawn-out, circus-like cage fight.

The focus has turned not on achieving the “consent of the governed,” but on obtaining the vote of the governed. Therefore, a few months (or in the case of the 2008 presidential election, years) before the election, politicians drop everything they do to become full time hand-shaking, baby-kissing, good-listening “public servants.”

In other words, they go on the campaign trail. Politicians are speaking with their constituents, listening to the concerns they have, staying up to date with every issue and taking a stand, claiming that they will avenge the wrongs done to their people and unite the city, county, parish or state.

Much of this is clearly a façade that has become a necessary, though at times, deplorable, element of our political system. However, after the façade is removed, what remains resembles a politician truly doing his or her job – listening to the people, reaching out to communities, staying on top of the daily issues and calling fellow leaders to more diligent service.

Unfortunately, these virtues rarely carry on past election season. We saw this with the last presidential election that lasted for a brutal, two-year stretch.

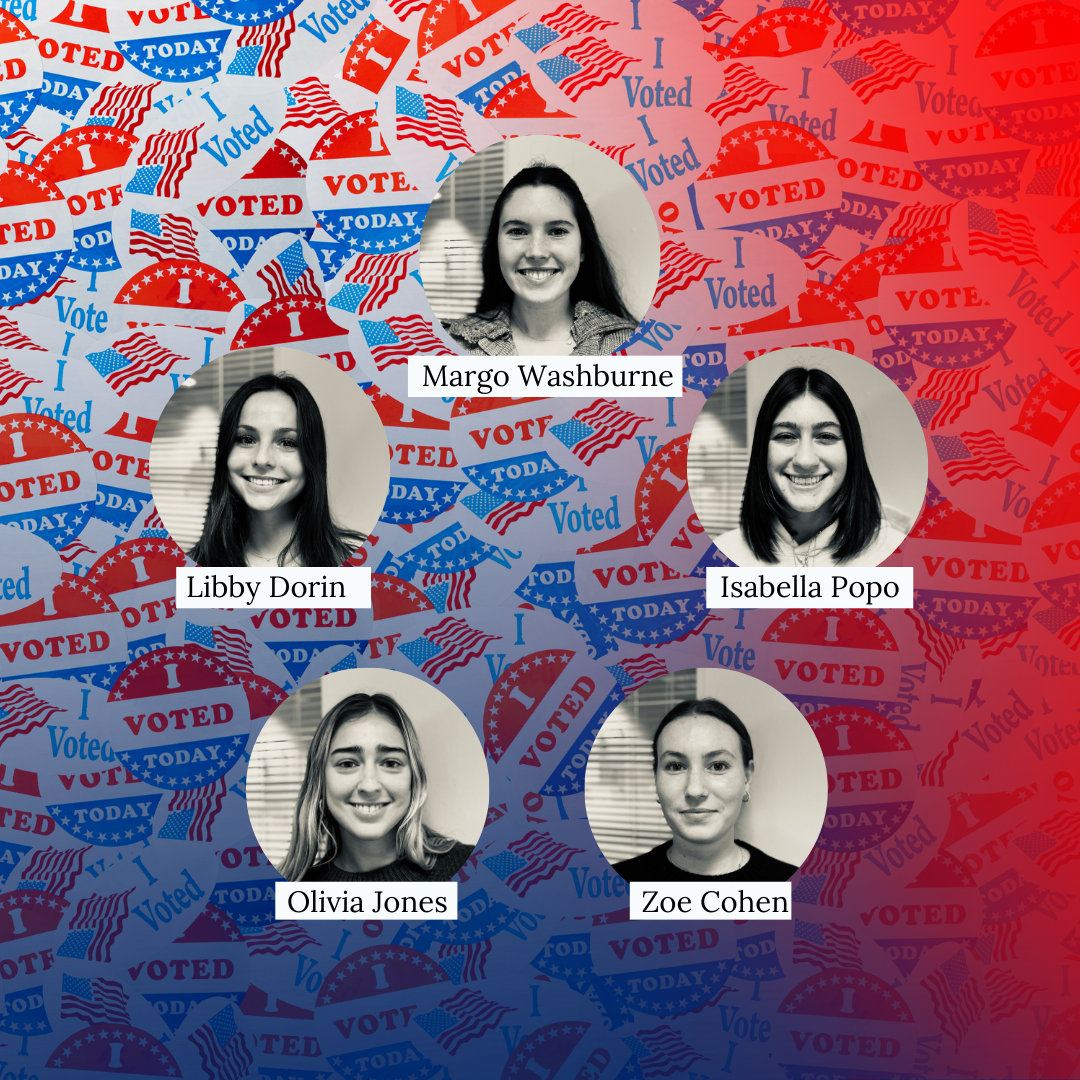

We witnessed the same trend with our SMU student body elections. More than a handful of senators were vying for the presidential seat and four more were competing for the vice president and secretary roles- not to mention innumerable students who were running for the coveted senatorial positions while promising reams of legislation along the way.

During the SMU election cycle, the opinion of the students and the unity of the campus were hoisted upon sanctimonious pedestals and called upon by every individual running for office.

The student candidates traveled diligently from student group to student group. They loitered in the busy corridors of Hughes-Trigg Student Center and Dallas Hall just to stop you and tell you how they hoped to represent you. They pestered you with endless Facebook messages, group invitations and advertisements.

The diligence, passion and energy funneled into a political campaign seem very impressive, even compelling, in the moment. Incredibly, the public servant is actually serving the people. When the waves of the electoral ocean subside, however, a mundane political reality surfaces, and the victor emerges with the “consent of the governed.”

Politicians are meant be servants of the people and should concern themselves with the necessary consent of the governed throughout their service. Likewise, citizens should give their consent cautiously, making clear the voice behind their vote. Indeed, it is “the consent of the governed” which made the “American experiment” such an innovative enterprise.

Drew Konow is a senior religious studies, foreign languages and literatures triple major. He can be reached for comments or questions at [email protected].