The social conversation at the beginning of January was crowded by controversial political action and protests. And one of the most debated events in terms of First Amendment freedoms was the removal of former President Donald Trump from multiple social media platforms. Regardless of political standing or opinion, the fact remains that censorship on much more extreme levels is happening worldwide. But no one in the country or on SMU’s campus seemed to know anything about it.

On March 3., I got the opportunity to visit my parents, who have established a semi-permanent residence in Uganda’s capitol of Kampala following my father’s work as a lawyer for Pepperdine Law School and their partnership with the Ugandan Judiciary. Although the dates of my visit seemed to be far from the January controversies, my firsthand experiences demonstrated how far the country of Uganda has to come in order to establish any form of fair or free elections.

Africa has long been clouded with controversy regarding authoritarian regimes and tumultuous elections. And this year, the election for the country of Uganda followed the same pattern. Following Twitter’s actions to remove Trump from the platform in early January, Uganda feared for the integrity of their election and decided to shut down the internet entirely. A nation-wide internet blackout is far more of an extreme action of censorship when compared to the removal of one political profile, yet I failed to see it even be mentioned in the public discourse on campus.

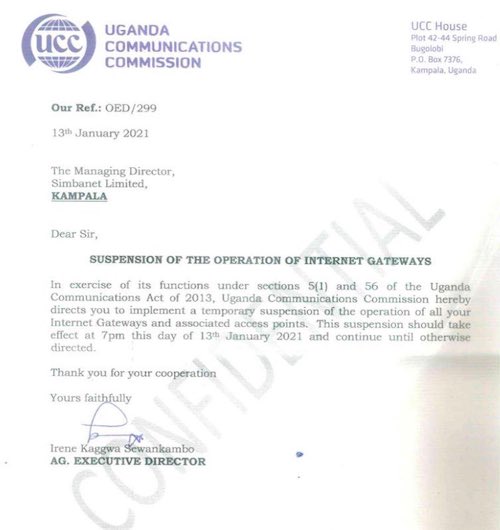

On Jan. 13, the Uganda Communication Commission implemented what they called “a temporary suspension” of all internet gateways according to Reuters. The internet blackout occurred the night before the presidential election in which long-time leader Yoweri Museveni faced popular singer Bobi Wine. Uganda had banned all social media and messaging apps just days prior with the president saying that the actions were in retaliation of Facebook’s removal of some pro-government accounts.

Twitter criticized the Ugandan government’s order for Internet providers to block social media. Via their Public Policy account, the company tweeted, “we strongly condemn internet shutdowns- they are hugely harmful, violate basic human rights and the principles of the #OpenInternet.” But many spoke out against Twitter’s statement, calling it hypocritical following their permanent suspension of Trump from the platform.

There were fears of election rigging in Uganda and Museveni’s resulting victory on Jan. 14 did not put these fears to rest. Wine planned to dispute the results, alleging that he has evidence that voter fraud occurred and cost him the election. Museveni reportedly received 5.85 million votes, contrasting to Wine’s 3.48 million.

The most concerning factor of both the censorship and the potential election fraud in Uganda is that no one in the SMU community seems to be aware that this is an issue or that it is even occurring. There is a widespread societal naivety in regard to any form of human rights violations that occur outside of our nation’s borders.

Mid-morning on March 15, my mother got news from fellow expats, via the American Embassy in Uganda, to avoid the downtown area of Kampala due to potential riots. A few searches on YouTube lead me to live footage of the riots, happening on a street I had visited just days earlier. Bobi Wine and fellow compatriots were peacefully and quietly marching, holding signs of protest against the government’s treatment of the election and those who had previously protested the election’s alleged unfairness. Wine was arrested that day but later released.

Although this event was concerning to me in of itself, the most shocking part was the fact that I stepped away from my computer for 10 minutes and refreshed the page. When YouTube loaded, the livestream of the protest had disappeared entirely. All coverage available on the platform was no longer available to view.

Though Uganda’s controversial election seemed to rest peacefully in the past, the government’s exercise of extensive power over outlets of speech has caused unrest to continue.

The opportunity that I had to see censorship firsthand gave me a new perspective on the generalized worldview of SMU’s population: self-absorbed and focused on only those issue that seem to be at the height of public debate.

Uganda has spent the last year playing host to a clouded political agenda that is actively faced with a sturdy and resent-filled public response. And my issue with SMU students is not that they don’t recognize that the actions of the Ugandan government are problematic, but that they don’t even know that these events are occurring to begin with. There seems to be great naivety that there are issues worthy of public debate and concern outside of the borders of the United States.

I would challenge those who constantly post about human rights violations in our country to not only rethink their reason for doing so, but to also investigate what is happening around the world. My fear for SMU students is that responses to issues can be overly performative. Not only does this fail to truly usher in any real change, but it pressures students to focus in on only a small number of potential threats to human rights. I want to encourage individuals to think on more of a global scale in all aspects of life.

If you truly want to make a change, your perception of human rights needs to expand to recognize shortcomings of countries other than our own. Although our country is far from perfect, there is a lot that we need to be grateful for, as countries like Uganda lack a lot of the freedoms that we take for granted.

The Daily Campus welcomes opinion contributions from students, faculty and community members. Submissions should be no more than 1000 words and are subject to copy editing. Please email submissions to [email protected], and include a cell phone number and a short biography. All pieces submitted to and published by The Daily Campus are under the publishing and editorial purview of the paper once published.