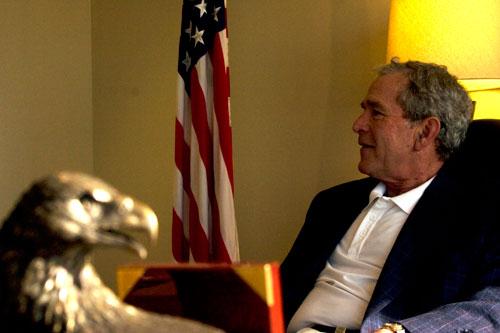

The Daily Campus politics editor, Jessica Huseman, interviews former President George W. Bush Dec. 21, 2010, in his North Dallas office. (JOSH PARR/The Daily Campus) (The Daily Campus)

To listen to audio of Jessica Huseman’s interview with President George W. Bush, go to our Politically Inclined blog.

When Air Force One touched down in Tanzania on Feb. 16, 2008, thousands of eager Tanzanians waited to greet then President George W. Bush.

The first lady of Tanzania wore traditional Tanzanian clothing adorned with Bush’s picture, as many of the women in the crowd did. The clothing read “Udumu Urafikiki Kati Ya Marekani Tanzania,” meaning “Long Live Tanzanian and American friendship.”

This was Bush’s second stop on his five-country tour of Africa that was largely focused on U.S. aid programs, most notably the President’s Emergency Plan For AIDS Relief (PEPFAR).

Press coverage at the time showed the road lined from the airport to the hotel where Bush and the first lady were staying with cheering Tanzanians and billboards of thanks for the help that Bush had extended to combat the pandemic of AIDS that had taken hold of the country and much of the continent of Africa.

Even with such celebration in Africa, the fact that Bush tripled U.S. aid to Africa to help prevent and treat AIDS, which according to a 2009 Stanford study, reduced the death toll from HIV-AIDS by more than 10 percent in targeted countries, saving over one million lives.

The former president talked about his African AIDS initiative in a recent interview in his Dallas office. PEPFAR will continue under the Obama Administration, and Bush will continue to address the AIDS epidemic through the Institute that will be part of the George W. Bush Center.

Bush attributes the original idea for PEPFAR to his then National Security Advisor Condoleeza Rice.

“When I was trying to convince her to be a part of my team she said ‘I hope you’ll focus on Africa,'” Bush told The Daily Campus. “Once you make the decision to focus on Africa, you can’t help but notice that HIV-AIDS is wiping out an entire generation.”

Bush said his decision to move forward in the fight against AIDS was his belief that “all human life is precious” and that “we were seeing human life disappearing basically because of a pandemic.”

He first announced his plans for PEPFAR in his 2003 State of the Union Address, in which he asked Congress to “commit $15 billion over the next five years, including nearly $10 billion in new money, to turn the tide against AIDS in the most afflicted nations of Africa and the Caribbean.”

From this initial announcement began a plan that would make the United States Africa’s leading contributor to the fight against HIV/AIDS. During the next several years, PEPFAR would partner with African governments to distribute antiretroviral medication, educate Africans in AIDS prevention and assist in combating the stigma that surrounded the virus.

In order to do this, the PEPFAR strategy was three fold: “Prevention, distribution of antiretroviral medications to save lives, and to deal with those that had been affected by HIV/AIDS, especially orphans,” Bush said.

But from the start, PEPFAR drew criticism because the program promoted abstinence.

The program was centered partly around the “ABC approach,” or “Abstain, Be Faithful and Correct and Consistent Use of Condoms.” This irked many who felt abstinence was ineffective.

But both Bush and Mark Dybul, who Bush appointed to head the administration’s fight against AIDS in 2006, felt that the ABC approach was misunderstood. It was originally developed in Uganda as an AIDS prevention technique and was not an idea of the Bush administration. And as an African strategy, Bush felt it would be most effective and appropriate.

Additionally, says Dybul, the meaning of abstinence was misinterpreted. Dybul, who served as deputy U.S. global AIDS coordinator and assistant U.S. global AIDS coordinator before taking over as coordinator, was recently interviewed over the phone.

“Abstinence really means just delaying when people become sexually active, no one was saying that people should never have sex,” he said. “You give different messages depending on the age and risk, so you don’t talk to the five year olds about condoms, but as you get older the messages change and the comprehensive approach is provided,” he said.

He also notes PEPFAR was very clear on the use of condoms to prevent HIV/AIDS. During the time of PEPFAR, Dybul said, the U.S. provided more condoms than the rest of the world put together – more than two billion of them.

“I understand where the controversy comes from, but it was misguided and incorrect about what we actually did, how we approached the program, and certainly the notion that we created the abstinence program that was actually designed in Africa is a little disingenuous,” Dybul said.

Dybul is not a person who nicely fits in to the stereotype of the Bush administration. As an openly gay independent who has donated to Democratic campaigns, Dybul admits that even he didn’t fully expect Bush to be as kind and open as he found him to be.

“It wasn’t just that I was welcomed – President and Mrs. Bush seemed to go out of their way to welcome us and to include my partner and me in White House receptions and dinners,” Dybul said. He said that Mr. and Mrs. Bush continue to go “out of their way” to ask how his partner, Jason, is doing.

“The more I am around them, the more I realize … that is how they treat everyone: with great graciousness and kindness.”

These traits, Dybul said, also helped Bush create a “fundamental shift in development from paternalism to results-based approaches.” Before PEPFAR, Dybul said that development often took the form of a wealthy nation simply telling a poor country what to do.

Dybul said this notion of development was almost “repugnant” to the former president. So, instead of instruction, Bush decided to partner with the “focus countries” of PEPFAR – nations that needed the most help.

“The old model of foreign aid was to say ‘we’re going to write you a check and we’ll feel better about it,” Bush said. “We said, we will support you if you design a program that is effective.”

It wasn’t just lack of funding and a misinformed notion of development that the program needed to combat, however. The stigmas that existed against HIV/AIDS were some of the biggest hurdles to overcome.

The misconceptions about AIDS led many Africans to refuse to seek testing or treatment, to treat those that were diagnosed as outsiders and to spread fallacies about how HIV could be cured or contracted.

“One way you deal with it is have leaders stand up and get tested for it to show how important it is,” Bush said. The president of Tanzania was tested for HIV on television. Bush said acts like these help to dismiss stereotypes and reduce the impact that they have.

Dybul said the change during the last few years in the form of increased education and treatment has also led to the understanding that it is a medical condition, helping to stem the number of people who refuse to be tested or treated.

Bush took his new fight against AIDS to the 2004 G8 conference, when the buzz around global warming was consuming international news. And even though the conference seemed to keep coming back to that topic, Bush pushed forward.

“My point was, you are dealing with an issue that may or may not be as severe as you think it is. But what is severe is people dying of AIDS,” Bush said.

He convinced several countries to make strong commitments to help the fight against the virus, but, Bush said, “They’ve been

a little light up to now” and their continued support “depends on whether the president of the United States will remind them of their commitment.”

Bush declined comment on his thoughts about the current administration’s handling of PEPFAR – as did Dybul, who was originally asked to continue in his position by the Obama administration, only to be asked to submit his resignation letter a month later over the controversy of his support of abstinence. Dybul would only say that he had the “greatest respect for the new global AIDS coordinator, who is a longtime friend and colleague and the entire global health and development team the administration has assembled.”

Dybul is now co-director of the global health program at Georgetown University and has also been appointed as a fellow in global health at the George W. Bush Center, where he will focus on finding optimal ways to provide health care to mothers and children in several African and Asian countries around the time of birth.

Dybul did say he believes that Bush deserves a Nobel Peace Prize for his work in Africa. “There was literally no global response until President Bush came forward and said enough is enough,” he said.

Dybul said that the global shift in the direction of development also warrants the prize. “If you look at this objectively, no one can say that that is not the ring of a Nobel Peace Prize.”

But, said Dybul, there is very little chance that Bush will ever receive the highly coveted award partly because Bush doesn’t seem to care about it.

“This was never about the president. We had instructions that we weren’t supposed to be out there getting him credit for it,” said Dybul. “When your whole goal is to serve, whether or not you get an award isn’t particularly important.”

For Bush, the overwhelming support he has gained in Africa seems to be award enough.

“I was particularly grateful of the outpouring of support in a place like Africa because it made me feel proud of the contribution of the American people,” Bush said. “I didn’t view it as a tribute to George Bush, I viewed it as a tribute to the people of America.”

Former President George W. Bush met with political journalist Jessica Huseman to discuss AIDS initiative PEPFAR. (JOSHUA PARR/The Daily Campus) (The Daily Campus)